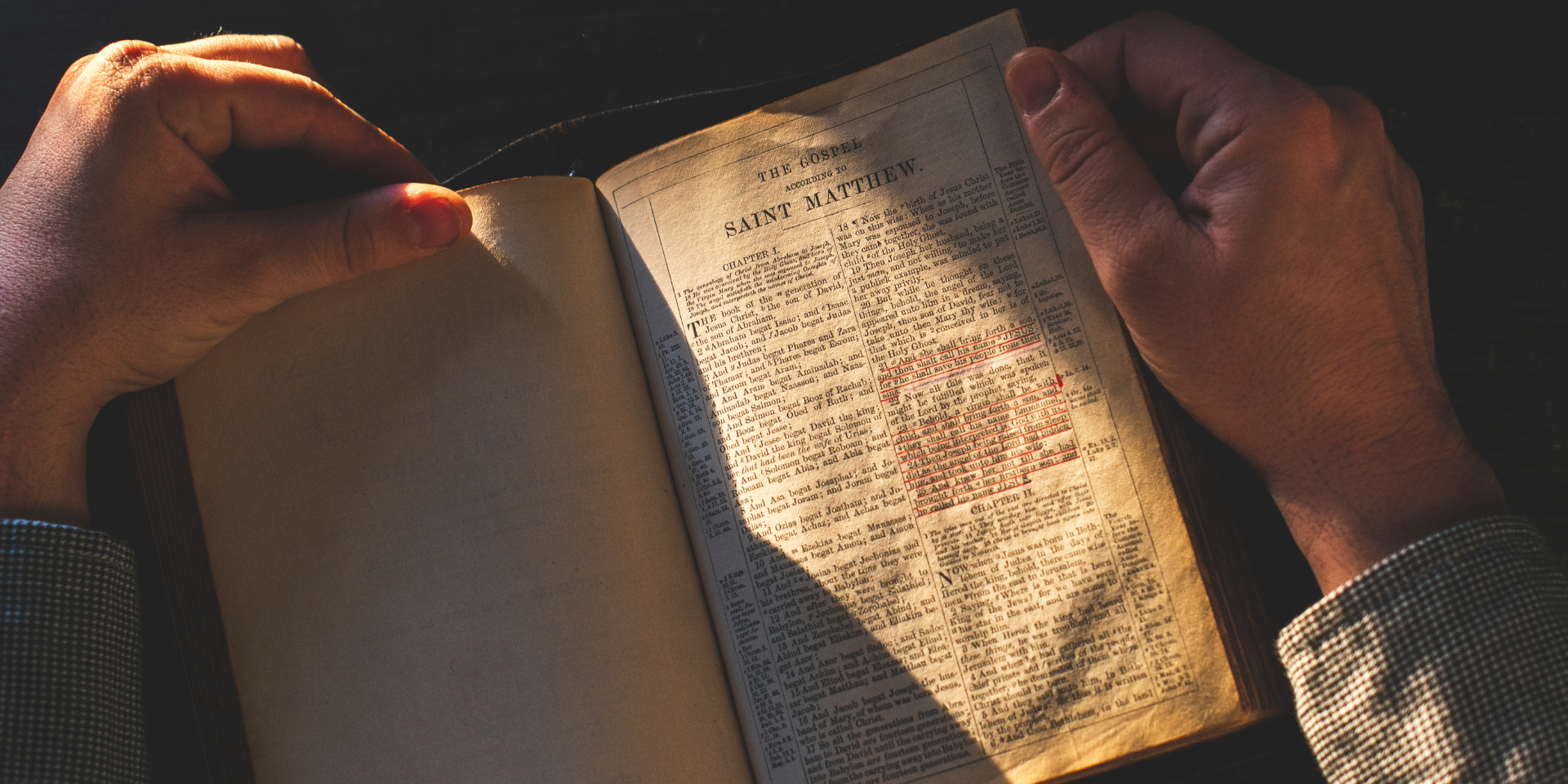

Many Christians say they take the Bible literally. They regularly spend time reading this Book they believe to be inspired by God and seek to understand how to apply it to their lives.

They study the Bible with their friends, are taught about it at worship services and read other books about the Bible to grow their own understanding of the text.

But is it even possible to take literally and live out the instructions of an ancient book—parts of which were written more than 3000 years ago—amid living some kind of normal urban life in the world today? What impact would that have on everyday life, relationships and spirituality? And would one’s life be better for all the effort required to take the Bible’s many commands seriously?

These are some of the questions that sparked journalist A J Jacobs in his quest to live literally as the Bible commands for a full year. Raised in a secular Jewish family in New York City, Jacobs describes himself as an agnostic, who has spent time considering many of the arguments for the existence of God but has never been convinced.

But the re-emergence of religion in the headlines and a personal interest in exploring his Jewish heritage—as well as an intriguing and potentially entertaining book project—launched Jacobs into his “year of living biblically.” His first task was to comb through the Bible to find as many commands, rules and instructions as he could.

From the Ten Commandments and the Golden Rule—“Do unto others as you would have them do to you”—to the obscure minutiae of the Old Testament’s laws of purity, Jacobs’s list totalled more than 700 specific instructions. Then, with a group of theological and spiritual advisers, he set about putting them into practice. And his resultant book—The Year of Living Biblically—chronicles this experiment.

The most obvious changes were his outward appearance—particularly his full, bushy beard. He also adopted the habit of carrying a small folding stool wherever he went, so as to avoid sitting anywhere that someone “impure” may have sat. His diet changed, as did his use of language and conversation.

Throughout the year, Jacobs spent time with a variety of believers: wildly dancing Hasidic Jewish men, a worship-like gathering of devout atheists, a family of Amish farmers, pilgrims and tourists at the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, a fundamentalist Christian mega-church, a group of Israeli shepherds, snake-handling Christians and of course, Jacobs’s own extended family, with their various stages of life and faith. All of these were trying to live faith of some description, most applying some elements of the Bible to the task.

Jacobs sought good deeds to do for others and, with his long-suffering wife, shared their quest to fulfil the Bible’s first command to humanity—“to be fruitful and multiply.” He also stoned—admittedly with very small pebbles—a self-confessed adulterer and participated in the kosher butchering of chickens. He experimented with prayer, practised blowing a ram’s horn shofar, and discovered a variety of stories and characters recorded in the Bible.

For a full year, Jacobs poured himself into his project and, of course, it impacted on his beliefs and attitudes. In his fumbling way, he came to feel that he had moved closer to the God he was still not convinced he believed in. He found himself becoming more tolerant of religion and of the many religious forms he encountered. And he felt that he had become a better person—more considerate of others and “addicted to thanksgiving.”

But perhaps the biggest question Jacobs’s quest raises is how the Bible is best applied to life today. Few believers go to the same lengths Jacobs did in taking it literally, although some of the believers with whom he spends time do have their own versions of this quest. And then, there are the situations that arise in today’s world that are not specifically addressed by the Bible. Gaps inevitably emerge when seeking to match text to life.

Both in his book and through the experiment itself, Jacobs argued that unless believers are prepared to go to at least similar lengths, they cannot claim to be literal literalists. In a sense, he is right. And that raises the question as to how believers choose what to take literally—and what to ignore, explain away or otherwise adapt to their own culture and circumstances.

If the text of the Bible itself is not the final authority—if something or someone else dictates what believers believe and apply to their lives—how do they determine what that something or someone else will be, and what continuing role exists for the Bible itself?

Perhaps we can find a hint in one of Jacobs’s earlier books. He is not a newcomer to this kind of immersion journalism: conducting an experiment in one’s own life and then reporting on its effects. In The Know-It-All, he read the complete Encyclopaedia Britannica as part of his “humble quest to become the smartest person in the world.” Among his conclusions at the end of this experience he states: “I know that knowledge and intelligence are not the same thing—but they do live in the same neighbourhood.” The same could be said of his use of the Bible. Rules and relationship are not the same thing—but they do live in the same neighbourhood. The relationship is between the believer and the God who inspired the Bible. In the context of that relationship, the Bible is less a list of rules than a collection of stories and examples.

Yes, people discover God by spending time with the Bible, and they can certainly find out more about God and what He is like in this way. The rules set out in the Bible are spiritual practices and disciplines that, when they become part of our lives, can be helpful in building a relationship with God. As Jacobs discovered, spending time with and intentionally practising these rules can draw us toward God and even help us become better people.

But the Bible is most effective when read from the perspective of one who has a relationship with God. With this way of seeing comes the realisation that the specific rules written down 3000 years ago are less important than the principles they demonstrate. These principles are more readily applicable to life today. And the relationship, growing knowledge and experience of God becomes the Someone and Something who guides us in applying the ancient wisdom of the Bible.

As God works in a believer’s life, the Bible becomes a source of guidance, wisdom and inspiration, which is so much more profound than Jacobs’s list of 700-and-something rules combed out of a dusty old manuscript. In the context of relationship, rules aimed at preserving and growing that relationship make more sense.

As Jacobs’s experiment demonstrates, taking the Bible literally can change—even improve—your life. But meeting God and letting Him speak in and through the Bible in the context of a relationship with Him will change you forever.

Nathan Brown is book editor at Signs Publishing Company in Warburton, Victoria. A version of this article first appeared on the Signs of the Times Australia/New Zealand website and is republished with permission.