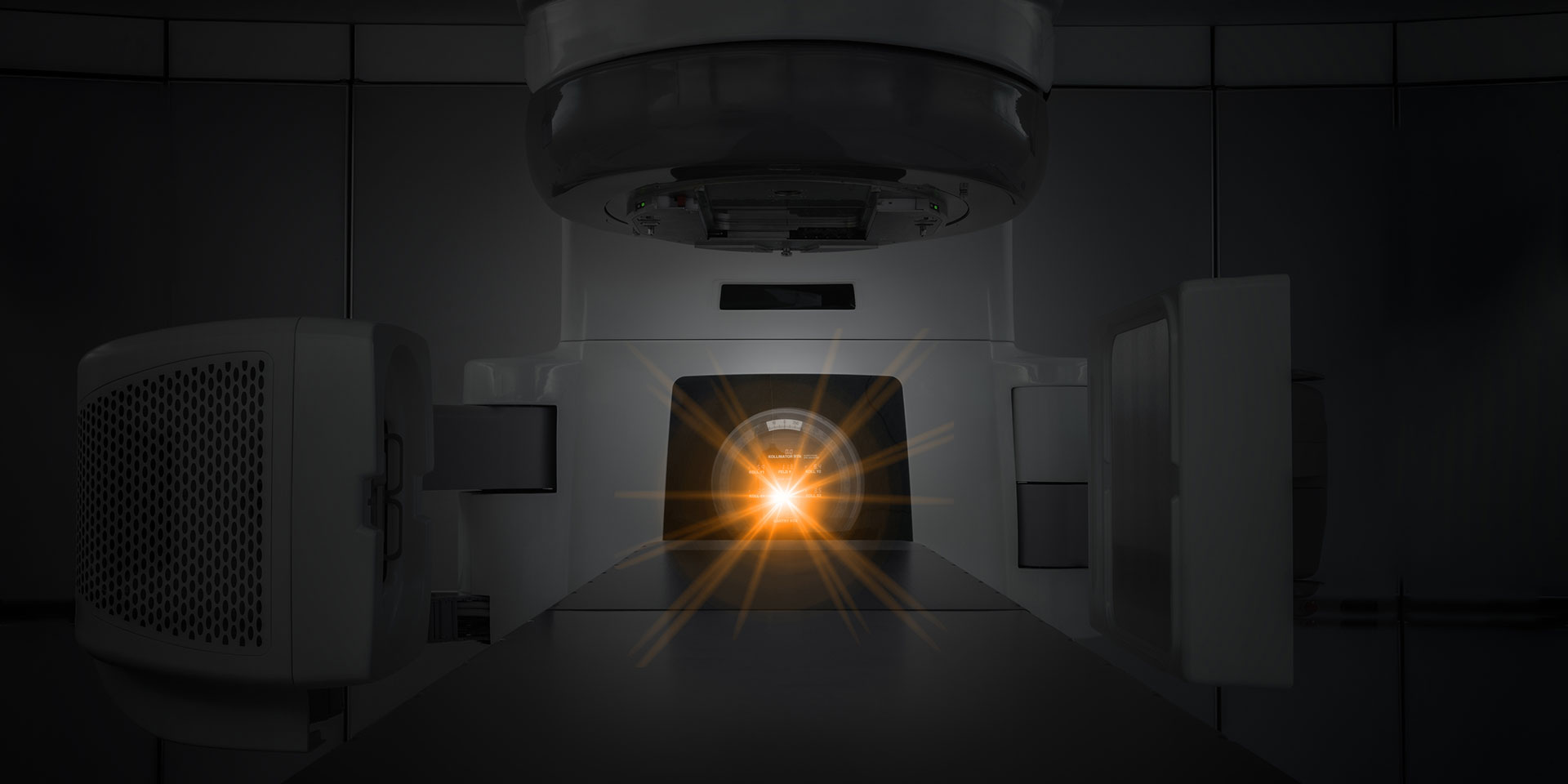

Lying on my back, naked except for a sheet draped over my lower body, arms tucked behind my head, I’m feeling vulnerable and exposed. The radiotherapist leaves the room. I’m all alone. I begin to panic as I anticipate the beams of radiation about to penetrate my skin.

I’m completely defenseless, at the mercy of the huge machine that is hovering menacingly near my body. My arms begin to ache due to their uncomfortable position. But I dare not move even a fraction; this would send the radiation off-course into surrounding muscle tissue, or worse still, into my heart. Inside I hear a voice screaming, Get off the table. Run! It’s not too late. But I can’t fight it. There’s no point. I close my eyes and surrender.

A few minutes later, it’s over. It feels so good to release my arms, and I grab the sheet and pull it up around my neck so I’m no longer exposed. My palms are sweaty. I feel like crying, but I quickly get dressed, say goodbye to the radiotherapist and go outside. I take a deep breath of the crisp morning air and look up at the sky. It’s a beautiful day. The tears I was holding back begin tumbling down my cheeks.

And so it began. My first session of radiotherapy. This was to be my routine for the following six weeks. My treatment involved 30 sessions: one a day, five days a week. After my initial feelings of panic, my anxiety eased as I got used to the routine. The radiation treatment itself was painless, although by the end of the six weeks my skin had become quite red in the area being targeted. Like a patch of bad sunburn.

Radiotherapy commenced about eight weeks after surgery. I had been diagnosed with the earliest stage of breast cancer: ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). This is when cancer cells are found in milk ducts, but have not spread into the surrounding breast tissue. According to Breast Cancer Network Australia, about 1600 Australian women are diagnosed with DCIS each year. And in New Zealand, DCIS accounts for 22 per cent of breast cancers detected via the country’s free breast screening program, according to Breast Cancer Foundation New Zealand.

You often hear medical experts say that early detection is vital. In my case the cancer was detected as a result of my first-ever mammogram. Tiny calcifications were visible on the X-ray images and a subsequent biopsy showed they were cancer cells. I underwent a lumpectomy, where the affected section of breast tissue was removed. The wound was then given a few weeks to heal before radiotherapy began. Radiation helps to destroy any undetected cells and to reduce the risk of the cancer returning.

To say the cancer diagnosis was a shock is an understatement. I was gobsmacked. I lived a healthy life. There was no family history of cancer. I had three young children in primary school. This can’t be happening to me, I thought. At the time I was working as a community newspaper journalist and almost felt like an expert on cancer—I’d been the newspaper’s health reporter for a number of years and had written many stories about people with cancer.

All types of cancer: prostate, lung, brain, bowel… even the rare case of a man who had developed breast cancer. I had written about new cancer-fighting treatments and technologies. I had sat with a young mum with terminal cancer and cried with her as she told me about the diary she was compiling for her four-year-old daughter, knowing she wasn’t going to see her grow up. It seemed unfathomable that I would end up with the disease.

But I did—that’s the ironic way life turns out sometimes. But I’m among the lucky ones as it’s now been 10 years since my diagnosis. No longer do I have to see my breast cancer surgeon each year; however I continue to have annual mammograms and keep a lookout for any changes in my breasts. I’m left with a permanent scar and breasts that look different.

And a simple hug or an accidental bump can give me a not-so-subtle reminder that the breast has suffered some serious trauma—a legacy of the radiation apparently. But I’m not complaining. I feel so lucky for my life; early diagnosis really does increase the chances of survival. I’ve been so blessed to have seen my children grow up into young adults. I’m all too aware that, sadly, not everyone gets that chance.

Going through an experience like this has certainly given me a wake-up call about what’s important in life. It has also prompted me to examine my physical, mental and spiritual health and make a few changes.

Physical

While I’d considered myself healthy before my cancer diagnosis, the reality was that, apart from being a vegetarian, I didn’t do anything else for my physical wellbeing. I was a busy mum juggling work and three small children. I wasn’t doing any exercise. I was snacking on junk food. I wasn’t even getting out in the sun—my vitamin D levels were later found to be seriously depleted. Now I do a brisk walk at least five days a week.

Each night I whip up a smoothie of fresh oranges and mixed berries, which are high in antioxidants. I snack on nuts and the occasional piece of dark chocolate. The results: I’ve lost weight; I no longer get headaches all the time; I feel more alert than I have for years.

Mental

One of my favourite things to do is get out in nature, especially in the bush. I find it the perfect antidote for a stressful week and for giving my mental health the boost it needs. I used to worry about a lot of stuff; I now realise that the “supermum” concept is a myth and I need to give myself a break.

Spiritual

My faith in God sustained me in the many anxious moments I encountered throughout my experience. I’ve also learned an important lesson from the radiotherapy room: while I have always liked to think of myself as very independent and in control, I’m actually completely defenceless and at the mercy of the evil forces that hover menacingly around me. There is no point trying to fight them by myself; God is there as my Defender and Guide. And He can be your Defender and Guide too. All we need to do is surrender our lives to Him.

This article first appeared on Signs of the Times Australia