His philosophy and theology dominated human thought for over a thousand years. Until Thomas Aquinas emerged in the 13th century, Augustine was undoubtedly the most important thinker of the medieval period.

Even beyond the medieval period, however, many of his views continued to influence human thought. His ideas about just war, original sin, time and eternity, the role of grace and will, and the relationship between faith and reason are still debated by philosophers and theologians today.

René Descartes adopted an Augustinian approach to many philosophical concepts, particularly with regard to reason. His contemporary, the philosopher Nicolas Malebranche, also clearly said that he was inspired by Augustinian philosophy, especially when it came to the theory of knowledge. H Grotius, G W von Leibniz, J S Mill, G Berkeley, and B Russell were all influenced by Augustinian thought in one way or another.[1]

Petrarch, Luther, Bellarmine, Pascal, and Kierkegaard were also influenced by Augustine’s ideas. Augustine’s psychological analyses can be seen in Freud’s work, as he was the first to explore the existence of the subconscious.[2]

During the Middle Ages, Augustine was the most quoted theologian, becoming one of the four great doctors of the medieval Western Church alongside Ambrose, Jerome, and Gregory the Great.[3]

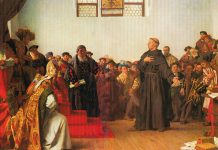

Augustine was also the favourite theologian of Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin. Thus, with his ideas being interpreted in different ways, Augustine became the most influential theologian in the entire Western Church, both Catholic and Protestant, and the most influential figure in the history of Christianity.

The age of Augustine

Augustine lived during the decline of the Western Roman Empire, which collapsed in 476, a few decades after his death. It was a time of the rise of Christianity (following the Edict of Milan in 313). The Church, emerging from persecution, was plagued by internal disputes and heresies: Arianism, Donatism, Manichaeism, and Pelagianism. Augustine lived in an era when the old civilisation was on the brink of collapse at the hands of the barbarians. He stood between two worlds—the classical and the medieval—urging people to wait patiently for the City of God.

Augustine—the man

He was born in 354 in Thagaste , North Africa (present-day Algeria), into a family where his mother was Christian and his father was baptised before his death. His parents made every effort to provide him with an education that would elevate him to the upper echelons of society. Thus, he left to study rhetoric in Carthage.

At the age of 17, far from his mother’s influence, he gravitated towards entertainment and pleasure. Following the social norms of the time, he entered into a concubinage relationship with a woman from a lower social class. While in Carthage, Augustine also became involved with the Manichaean movement, a heresy with which he remained associated for nearly ten years. However, he was too restless and his questions about the enigmas of existence were too important to be satisfied by such esotericism. Consequently, he turned to philosophy and was won over by Neoplatonism.

His conversion

In 384, he secured a position as a professor of rhetoric in Milan. It was here that he began his journey back to God. In Milan, he was captivated by the personality of Bishop Ambrose. Eloquent, intelligent, and polite, Ambrose possessed all the qualities needed to draw Augustine closer to God. Augustine’s mother, now a widow, also came to Milan to persuade her son to dedicate his life to God. Since his departure from home, she had prayed and wept constantly for his conversion. Recalling his mother’s experience with God, Augustine wrote in his Confessions: “And You heard her, O Lord, You heard her and did not despise her tears when, pouring down, they watered the earth under her eyes in every place where she prayed. You truly heard her.”

The experience in the garden marked the decisive stage of Augustine’s conversion in 384. While in the garden of his home, Augustine was moved to tears by thoughts and questions concerning his relationship with God. Suddenly, he heard a child’s voice nearby chanting a repetitive phrase: “Tolle, lege—tolle, lege” (“Take up and read”). His tears stopped abruptly. “I rose up, interpreting it no other way than as a command to me from Heaven to open the book, and to read the first chapter I should light upon.” He picked up the book and eagerly read Romans 13:13: “Let us behave decently, as in the daytime, not in carousing and drunkenness, not in sexual immorality and debauchery, not in dissension and jealousy.” “No further would I read; nor needed I: for instantly at the end of this sentence, by a light as it were of serenity infused into my heart, all the darkness of doubt vanished away.” It was the light that he had been unable to find in Manichaeism or Neoplatonism.[4]

After getting his life in order and dismissing his second concubine, he and his son were baptised by Ambrose by immersion. This took place in the year 387. Following the deaths of his mother and son, he became bishop of Hippo, the second largest city in Africa after Carthage, in 396. He served there until his death in 430.

Augustine—the work

Augustine’s work is remarkable for its vastness (200 letters, 500 sermons, and 100 theological and philosophical works have been preserved) and diversity. As a polemicist, he successfully combated the major heretical movements of his time: Manichaeism, Donatism, and Pelagianism.

His best-known work is the autobiographical Confessions, widely regarded as a masterpiece of its genre. Right at the beginning of this book is his frequently quoted statement: “You have made us for yourself O Lord and our heart is restless until it rests in you.” Other famous maxims come from this book: “Give me chastity and continence, but not just yet, “A man ruled by passion is as uncontrollable as a torrential flood or hot wax”; “Hate the sin, but love the sinner”; “Evil is the absence of good”; and “If friends pervert through their flattery, enemies often correct through their insults.”

Much of Augustine’s fame, however, stems from his work De Civitate Dei (“The City of God”). Shocked by the sack of Rome by Alaric in 410, the Romans explained the disaster as divine retribution for the presence of Christians. Augustine, on the other hand, pointed out that Rome had suffered many calamities even before the advent of Christianity. He saw two cities in the world: the heavenly city and the earthly city: “the earthly by the love of self, even to the contempt of God; and the heavenly by the love of God, even to the contempt of self.” The city that was to endure was the city of God.

The book outlines the first real philosophy of history, representing Augustine’s contribution to our understanding of God’s role in history. God is the creator and lord of history. Other well-known works by Augustine include: Retractions, in which he revises misconceptions from throughout his life, and On the Trinity, in which he expounds the Trinity thesis.

Augustine—limitations

Although he was a great theologian, Augustine did not create a wholly biblical theology. He contributed to the development of the doctrine of Purgatory and all its consequences. He exaggerated the value of the sacraments and supported the doctrine of regeneration through baptism. He promoted the postmillennialist thesis, which states that the return of Christ would take place a thousand years after the Incarnation. Despite these errors, he is considered a precursor to the Reformation for emphasising the role of God’s grace in the salvation of humanity. He was canonised by the Roman Catholic Church because he claimed that it distributes God’s grace through the sacraments.

Despite these limitations, it is widely accepted that, between Paul and Luther, there was no one else in Christianity of higher moral and spiritual stature. It has been said that Augustine “was the most complete man in history, combining holiness with science, speculation with faith, and action with contemplation to an unparalleled degree”.[5]