Aurelius Augustine (354-430) is known for the stirring Christian experience he described in his Confessions and for the seminal theological thought that has shaped theology to this day.

The first Christian to be condemned to death by other Christians for differing theological views was Priscillian, Bishop of Ávila. The execution took place in 385 and, despite the protest of Pope Siricius at the time, the condemnation to death of those considered heretics became a common practice in the Middle Ages. The influential theologian Aurelius Augustine played a crucial role in this.

Augustine (354-430) is known for the stirring Christian experience he described in his Confessions and for the seminal theological thought that has shaped theology to this day. But Augustine has also been called the “prince and patriarch of persecutors” and blamed for legitimising persecution in the Catholic Church with his ideas.

Augustine lived in an age of violence. The death penalty and torture were commonplace in the society of his time. Yet Augustine was not just influenced by his times. “In justifying religious coercion, he also thought about it: he had reflected on why he was advocating such a policy and, so, he knew to what extent he was prepared to apply it.”

The Donatist crisis

Augustine was ordained a priest in 391 and became Bishop of Hippo four years later. In his early days, he was an advocate of religious tolerance. One may enter a church without permission, he said, approach the altar without permission, receive the sacraments without permission, but believe only if he wishes.

At the time, North Africa was in the midst of a crisis that had been going on for almost a century. Two Christian factions were fighting over legitimacy. The Caecilians believed that those Christians who had handed over the Scriptures to the Roman authorities[1] during the persecution of Diocletian (303-305) should be forgiven and not be rebaptised. The Donatists[2] believed that traitors had to be rebaptised and could no longer hold ecclesiastical office.

Over time, the schism deepened to the point where the two factions were essentially different organisations with different bishops and separate churches. Eventually, the Caecilians established themselves as the true Catholic Church, and the Donatists were persecuted and scattered.

In Hippo, where Augustine was bishop, the Donatists outnumbered the Caecilians. In the early years of his priestly and episcopal ministry, Augustine used the path of dialogue in dealing with the Donatists, and “emphasised mere pacific means of persuasion: personal contacts, writings, public discussions.” Moreover, Augustine was opposed to imperial legislation that provided for the use of force against the Donatists.

The Donatists, aware of the great theologian’s intellectual and rhetorical abilities, refused to attend meetings and dialogue with him. What is more, a breakaway wing of the Donatists (the Circumcellions) began to use violence against the Caecilians, and some of Augustine’s friends and followers in his jurisdiction suffered.

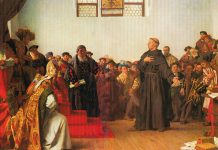

Faced with the stubbornness of the Donatists in refusing dialogue, the growing violence of one wing of the Donatists, and the voices of fellow bishops who favoured state involvement in resolving the crisis, Augustine finally took a hardline stance against the schismatics. The shift was not merely contextual, but Augustine, fine theologian that he was, constructed a theology of coercion that would have great influence in the centuries to come.

“Love and do as you please!”

Some readers will be surprised to learn that this phrase of Augustine’s refers to the conversion of the Donatists. In this context, Augustine preaches dilige, et quod vis, fac,[3] as a principle for distinguishing the wrong forms of religious coercion from the right ones. Love and truth must be the primary concerns. Love for the truth and love for others prompt one to lead the erring back to the truth by the way of love.[4]

The Church used Augustine’s theological arguments, but did not adopt his pacifist approach.

As such, as long as the motivation is love for the other, any means, even violence, can be used to win them back. Augustine interprets the parable of the wedding banquet in Luke 14 as referring to the use of coercion for the good of those outside. The parable says that the master ordered the servants to compel the unwelcome guests to enter (compelle eos entrance—Luke 14:23). The feast symbolises the unity of the Church, and the unwelcome guests are schismatics and heretics.[5]

A second argument is drawn from the conversion of the Apostle Paul. Augustine says of him that he was converted out of necessity (ex necessitate), because he was struck blind on the road to Damascus. According to the great theologian, conversion is a moral process involving a paradox of external coercion and internal development, fear and love, constraint and freedom.[6]

Augustine argues that the state must be involved in the coercion of the Donatists. He draws inspiration from the Old Testament, where there are many instances of the punishment of unbelievers being laid down in law. The new reality of a spiritual Israel supposedly would make the method of coercion applicable, as faithful kings were ordained by God to maintain order and peace (cf. Romans 13). The state is seen as a healing physician and an educating parent. Although state intervention is sometimes painful, its purpose—love and communion —justifies its use.

Augustine and the Middle Ages

Despite his doctrine, in practice Augustine promoted persuasion rather than coercion, even after he had accepted state intervention in dealing with the Donatists. He expressed his inner turmoil over the use of punishment as follows: “What shall I say as to the infliction or remission of punishment, in cases in which we have no other desire than to forward the spiritual welfare of those in regard to whom we judge that they ought or ought not to be punished? What trembling we feel in all these things, my brother Paulinus, O holy man of God! What trembling, what darkness!” (cf. Psalm 55:5, 6)[7].

This man of high theological spirit did not want to abuse his neighbour. He wanted the return of the lost. And if, after years of trying, dialogue and kindness did not work, he felt that perhaps moderate coercion would help them. But in the Middle Ages the Church did not follow Augustine. It used the fine theological arguments of Augustine, but it did not adopt his pacifist approach.

Strip away for a moment the basis of honesty and sincerity in this attitude, and Augustine’s ideas become false, terrible and insidious.[8] This is precisely why the Middle Ages happened as they did, and why Augustine’s arguments were used extensively in the rhetoric and anti-heretical campaigns of the period.