At the age of 34, he moved the American people with a speech about his biggest dream. At 35, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. At the age of 39, his life ended suddenly, with Martin leaving his dream as a legacy to the next generations.

Michael[1] Luther King, Jr. was born in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1929. From childhood, he experienced firsthand the consequences of racial segregation in twentieth-century America. People of colour were considered inferior, so they were deprived of many of the privileges white people had, simply because of the colour of their skin. Black children went to different schools than white children. Black passengers were required to occupy only the back seats of the buses and to give them up to any white citizen who asked them to do so. African Americans could not eat at the same restaurants as white people or even drink water from the same wells. Cinemas had two entrances: one for white people and one for people of colour. Discrimination, injustice, and inequality were part of everyday life.

Initially, Pastor King

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were all pastors. Young Martin’s decision to follow the same path was therefore not a surprise. Although he went down in history more as a civil rights activist, King was first and foremost a pastor. Before his speeches kept politicians in front of televisions and impressed millions, King influenced his church with his sermons.

Lewis Baldwin, professor of religious studies, said that King’s major achievements revolved around his pastoral vocation. The Bible held a special place in his life. Ever since he was a teenager, he stood out for the zeal with which he memorised biblical verses to recite them in front of the church pastored by his father. He graduated with a Bachelor of Divinity at Crozer Theological Seminary in Upland, Pennsylvania and received his PhD degree from Boston University, with a dissertation titled “A Comparison of the Conceptions of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman.”

King’s thinking and civic activism were strongly rooted in the Judeo-Christian tradition and complemented by his faith in God. “King remains one of the most influential religious leaders of the twentieth century. His efforts impacted not only the Christian Church but also American society and the global community,”[2] believes author and activist JB Hill.

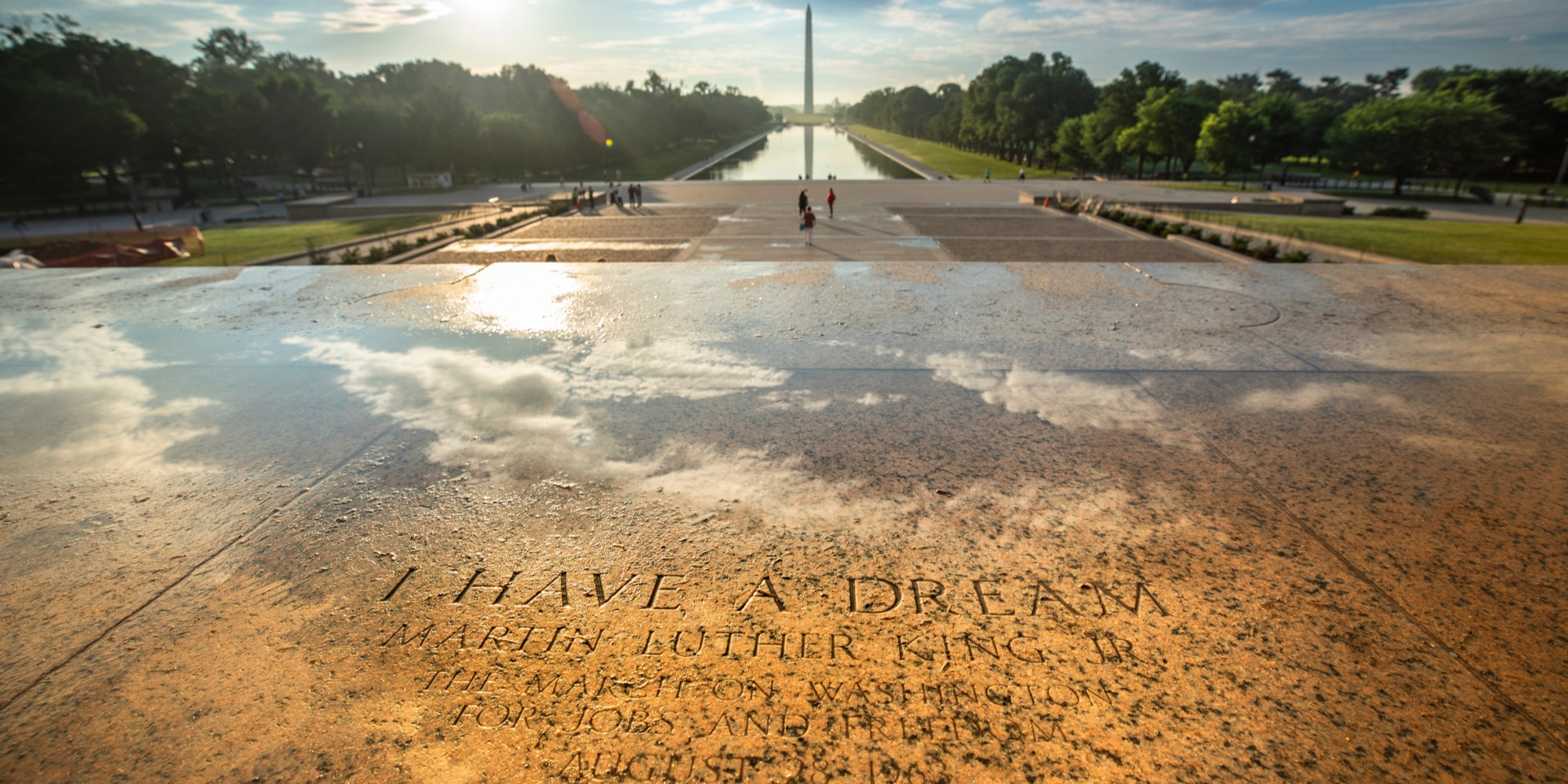

“I have a dream”

The march on Washington, on August 28, 1963, was one of the emblematic moments of King’s activity. More than 200,000 people of colour (as well as white people) gathered and demanded equal rights for all American citizens. King delivered the speech known today as “I have a dream” on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character,” King said. His dream—that the sons of slaves and those of slave owners would one day sit at the same table, as brothers and equals—produced strong responses. The next day, New York Times columnist James Reston wrote: “Dr King touched all the themes of the day, only better than anybody else. He was full of the symbolism of Lincoln and Gandhi, and the cadences of the Bible.” In the same year, Time Magazine named him “Man of the Year.”

To the mountaintop

Like any public and influential person, Martin Luther King, Jr. was controversial, contested, and accused of being undeserving of his fame. He was accused of having ties to communist organisations, that his doctoral dissertation was plagiarised and that the “I have a dream” speech was taken from the sermon of another African-American pastor. Beyond the more-or-less proven accusations, King remains one of the most important voices of the twentieth century, a voice of Christian formation. His rights movement later inspired and shaped social and political protests around the world. King explored and promoted concepts such as freedom, equality, justice, and human dignity, and attempted to (re)build them on the foundation of the Bible and the Christian faith. “Just as the eighth-century prophets left their little villages and carried their ‘thus said the Lord’ far beyond the boundaries of their hometowns… I too am compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my particular hometown,”[3] wrote King.

He started the freedom crusade from the idea that God is the supreme Being who intervenes in human history because He wants the best for all people. He is not a distant Being, King believed, but the “mother” and “father” of the orphans, a God who stands by those who suffer. His interpretation of the Christian Gospel was built from the perspective of the sufferers and the wronged. The gospel preached by King targeted concrete social needs. In his opinion, God chose people as His agents for the change of individuals, society, and institutions.

On April 3, 1968, King delivered the “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech, comparing himself to the prophet Moses, who saw from a mountaintop the Promised Land and the hope of a better world. “I’m happy tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord,” King said in the speech. The next day he was shot dead, but the gospel of freedom survived him, reshaping America.