Urban alienation is one of the great themes approached critically by many artists.

The industrial revolution[1] brought with it an increased importance given to the city. Industrial cities, metropolises, and conurbations were created to accommodate industry and related activities. The industrial revolution was followed almost immediately by an impressive demographic pressure in the cities and a draining of the village population, the industrial society being a profoundly urban one.

The ideological and material transformation brought about by the industrial revolution profoundly affected the social, economic, and cultural structures of Western civilisation, marking a major turning point in the history of humanity. Modernity can be understood as a “historical stage of Western civilisation—on the basis of which we can place the industrial revolution that brought with it the technological advance and the progress of science, as well as socio-economic mutations, which are prerogatives of capitalism…” Ciprian Lupşe says.[2]

The metropolis in art

“Metropolis,” the photomontage made in 1923 by the Dutch artist Paul Citroen, is one of his best-known works. The artist imagined himself in the role of an urban architect, reconstructing an imaginary city, composed of the emblematic buildings of the great metropolises (skyscrapers, the Eiffel Tower, shopping galleries, etc.), which mixes the past with the present and the future. The work is made up of fragments of photographs representing buildings arranged over the entire surface of the painting to give the impression of accumulation and chaos.

The buildings chosen make a direct reference to the industrial period, through new materials—concrete, metal, glass—and through public transport networks, which are signs and testimonies of an emerging consumer society. The collage draws attention to the fact that the city, which has become a metropolis, has grown in height and width, with its noises, movements, and lights mixing in an organised agitation, in the middle of which people seem to be not only lost, but lost sight of.

The Austrian-German-American filmmaker Fritz Lang, a representative of German expressionism, was inspired by the work of Paul Citroen, making in 1927 the science-fiction movie Metropolis (the most expensive movie of the silent era in the history of cinema). The action of the movie takes place in a city of the future, strongly divided between the working class and the city leaders, a dystopian society[3] in which rich intellectuals lead a life of luxury, ruling the city from the top of gigantic skyscrapers, and oppressing the workers who basically ensure the functioning of the city, living in the unsanitary basements of the imposing buildings.

The movie follows Freder, the son of the lord of Metropolis, who meets a young working-class girl, Maria, and is fascinated by her. Freder descends from the heights, following her into the underground world and is horrified at the the living conditions of the workers. The society in the futuristic city imagined by Lang seem to be the projection of a distant (and undesirable) future, but at the same time an allegory of the present, in a world caught in the rush for profit and selfish comfort.

The metropolis in architecture

Fritz Lang confessed in an interview that the idea for the movie was born when he first saw the skyscrapers of New York City in October 1924. Describing his first impression of the city, the director compared the metal and glass buildings to a luxurious stage set, dazzling and hypnotising, hanging from the dark sky.

The exterior of the city in the movie Metropolis is strongly influenced by the Art Deco movement, an eclectic style that in architecture meant elegance and charm, functionality and modernism. In the 1930s, the style gained international notoriety, its structure being based on symmetry, monumentality, and mathematical geometric forms—a direct consequence and a materialised expression of industrialisation and the evolution of new technologies.

The architecture imagined in the movie gives rise to a city that unfolds vertically, in which the human becomes increasingly smaller in the face of technological progress, the dimensions of the city being overwhelming. The images of the movie present a stratified (but also tangled) urban agglomeration, dominated by imposing buildings, automobiles, trains passing from one building to another on suspended bridges and aeroplanes flying between skyscrapers.

Life in the metropolis

Since the beginning of the 20th century, German sociologist and philosopher Georg Simmel[4] observed that the psychological basis on which the metropolitan individuality is built is an intensification of the emotional life of the person due to the rapid and continuous exchange of external and internal stimuli. The alert and constantly increasing pace of change in the modern urban landscape (new buildings, traffic, street advertisements), and the unexpected and violent change of stimuli that can be perceived at a single glance consumes the viewer’s mental energy.

Due to the intellectual character of mental life in the big metropolises, the metropolitan psychological type reacts primarily in a rational way, without emotional involvement. Despite the influences of postmodernism[5], contemporary thinking is still particularly concerned with practical aspects, with numbers and calculations.

The exactness of the calculation of practical life, resulting from the financial economy, corresponds to the ideal of science to transform the world into an arithmetical problem and to place all things in a mathematical formula. In the modern world, we want everything to have an explanation, to be accurately demonstrated and calculated: time, money earned and spent, and, eventually, even life.

The financial aspect of life refers to what is common to all—in other words, the value and counter-value (in money) of a thing or a person, a fact that reduces human quality and personality to a purely quantitative level. For contemporary consumerist society, time is money, as Benjamin Franklin said; today everything is focused on money.

The accuracy and precision—to the minute—that life in a big city demands results in an unbalanced emphasis on the impersonal component of the modern human’s psyche and, at the same time, a strong tendency towards an egoistic individuality.

In Georg Simmel’s opinion, there is no other psychic phenomenon that is as strongly linked to life in the modern metropolis, like the personality of the contemporay human—indifferent, tired, and individualistic. The effects of this life are superficiality and alienation. All these facts are primarily the consequence of the rapid and contradictory change of stimuli, the nervous system being thus strained, exhausted, and deprived of any recovery time, an excess that ultimately leads to the self-isolation of the individual, as a defensive reaction.

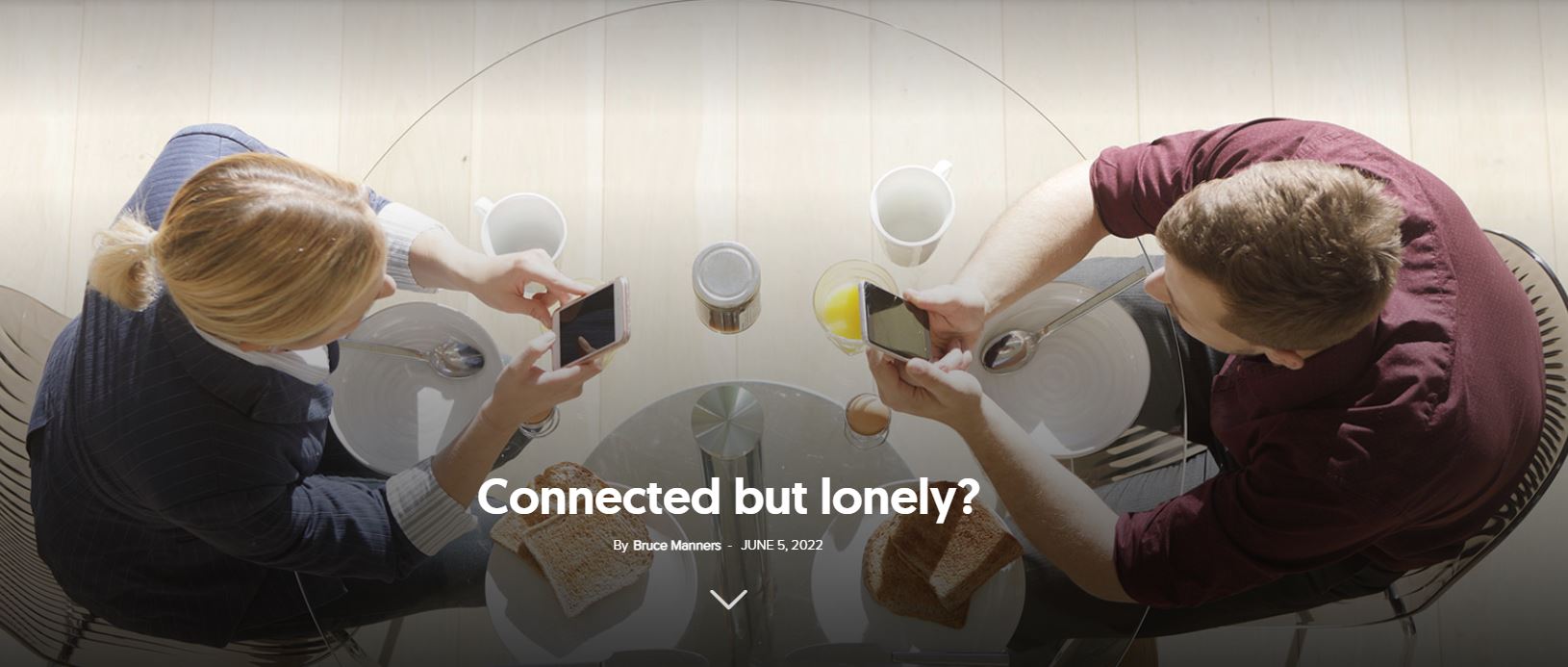

Probably nowhere does a person feel more lonely and abandoned, more isolated or alienated than in the midst of a wave of people in a metropolitan crowdedness. The alienation of contemporary society caused by turning inwards creates a problem at the level of a correct perception and understanding of the surrounding reality. As a result, the meaning and value of the distinctions between things are perceived as unimportant.

Life in a big metropolis is in great contrast to that in the countryside or even in smaller towns, where, from a mental-sensory point of view, the rhythm of life is slower, calmer and more regular. That is probably why, by comparison with the crowded, agitated, and overburdening city, Lucian Blaga wrote the following lines in the poem, “Spirit of the Village”: “…I believe that eternity was born in the village. Here every thought is slower, and your heart throbs at a quieter pace, as if beating not in your chest but somewhere deep in the earth….”