“‘The days are coming,’ declares the Sovereign Lord, ‘when I will send a famine through the land—not a famine of food or a thirst for water, but a famine of hearing the words of the Lord. People will stagger from sea to sea and wander from north to east, searching for the word of the Lord, but they will not find it’” (Amos 8:11-12).

Often, I’ve pondered upon reading Amos’s prophecy, how it could come to pass in a highly technologized world where data storage and textual information are limitless, where the printed Bible is so accessible, and the internet instantly transports it to every corner of the globe. The wandering from sea to sea would imply the total absence of electronic and electrical means of communication, even transportation, of physical mediums for storing biblical texts, and more seriously, the absence of people who could still know it. However, how immense would a cataclysm need to be to strip the planet of all these?

The sign of deliverance

In 1985, four years before the fall of the communist regime, a miraculous event occurred in Romania, inconceivable to us at the time: the renowned American pastor and evangelist Billy Graham visited Romania. Here, few people knew him, only some neo-Protestant Christians, but he was an influential man of God for millions worldwide, esteemed by state leaders, welcomed in many democratic or less democratic countries. Yet, in the midst of Ceaușescu’s dictatorship, without being publicised, without his visit announced on the news, the American pastor effortlessly gathered around 100,000 people in Timișoara. It was a spontaneous assembly of all those who had heard of him and were interested in what he represented.

To convey to today’s youth the magnitude of the reaction sparked by Billy Graham in the hearts of many Romanians, I would like to make a few clarifications. This is because I have encountered students who, with genuine interest but also with a somewhat guilty ignorance imparted by their history teachers, asked about the meaning of expressions such as “personality cult” or “political imprisonment.”

The first expression refers to a social phenomenon specific to totalitarian political regimes and dictatorships, where the supreme leader is excessively praised, applauded, and adulated through mass media, cultural institutions, education, and other entities subordinated to them. This forced adulation, done on command, is not based on merit but rather out of fear, interest, or servility because the supreme leader concentrates in their hands both political and military power, economic influence, and sometimes even religious authority. They embody the state and the party (in the case of the existence of a single party). The concept of “personality cult” dates back to the time of Soviet Union President Nikita Khrushchev, who succeeded Stalin, but the phenomenon represented by the concept is as old as time itself (think, for example, of the cult devoted by subjects to the Roman emperor Nero).

One of the sociopolitical instruments of the “beloved leader” was the secret police, a militarised apparatus for control, investigation, and maintaining the existing order and political status quo, which acted repressively against its own population. It was aggressive, vigilant, and reactive to any form of protest or challenge to the supreme leader’s personality, and it could not only deprive individuals of freedom through detention but also restrict almost all the freedoms guaranteed to individuals by human rights (freedom of conscience, expression, movement, association, initiative, practising religion, etc.).

Political imprisonment was one of the consequences of repression against citizens expressing political opinions other than the imposed one. Naturally, in court, charges were brought as if for common law offences, as there was no official admission in socialist and “democratic” Romania that there were political prisoners who were beaten, tortured, intimidated, threatened to become informants for the political police, called Securitate, accused of treason, sentenced, locked up in asylums, or even killed. Sometimes, they didn’t even publicly communicate their ideas, but the political police’s intrusions into private life, even in intimate journals, were commonplace. There were numerous cases, especially in the 1950s where denunciations to the Securitate were anonymous, designed by malicious individuals who had something to gain from informing on acquaintances. Still, these denunciations were considered and resulted in arrests, dismissals from positions, layoffs, expropriations, exclusions from universities, etc. Eyewitnesses know cases of students being excluded for ridiculous reasons, such as stating that they don’t like Soviet films or asking at the library about a blacklisted author (such as Lucian Blaga, Nicolae Iorga, Immanuel Kant, etc.) or for lending their meal card to colleagues suspected of being “enemies” of the party.

In that society with an atheistic ideology, the repressive apparatus extended its “activity” to churches.[1] Believers were intimidated or threatened at their workplaces or “via the party line.” Others were interrogated or imprisoned for their religious faith; some for observing the Sabbath, for spreading Bibles in communities, for refusing to become “informers,” or engaging in innocuous activities but viewed with great suspicion by authorities, etc.

Under such conditions, religious manifestations were merely tolerated, especially those of the majority church, but by no means encouraged. Eyes were turned away from church events related to major religious holidays throughout the year, Easter, Christmas, and religious services for baptisms, weddings, funerals. I myself remember how, on Easter night at the Orthodox church in town, we, the participating students, were covertly watched by certain teachers with secret informant roles.

In these conditions, imagine what a bright, unforeseen event it was for a pastor to come and remind people, in public, about God! Even for those indoctrinated to believe that the world from which he came was the “backward” world of “rotten, decadent” capitalism (according to the wooden language of communist ideology), his personality commanded respect and brought a ray of hope for our future. It was a signal that the free world hadn’t forgotten us, hadn’t abandoned us. It reminded us that every dictatorship has an end.

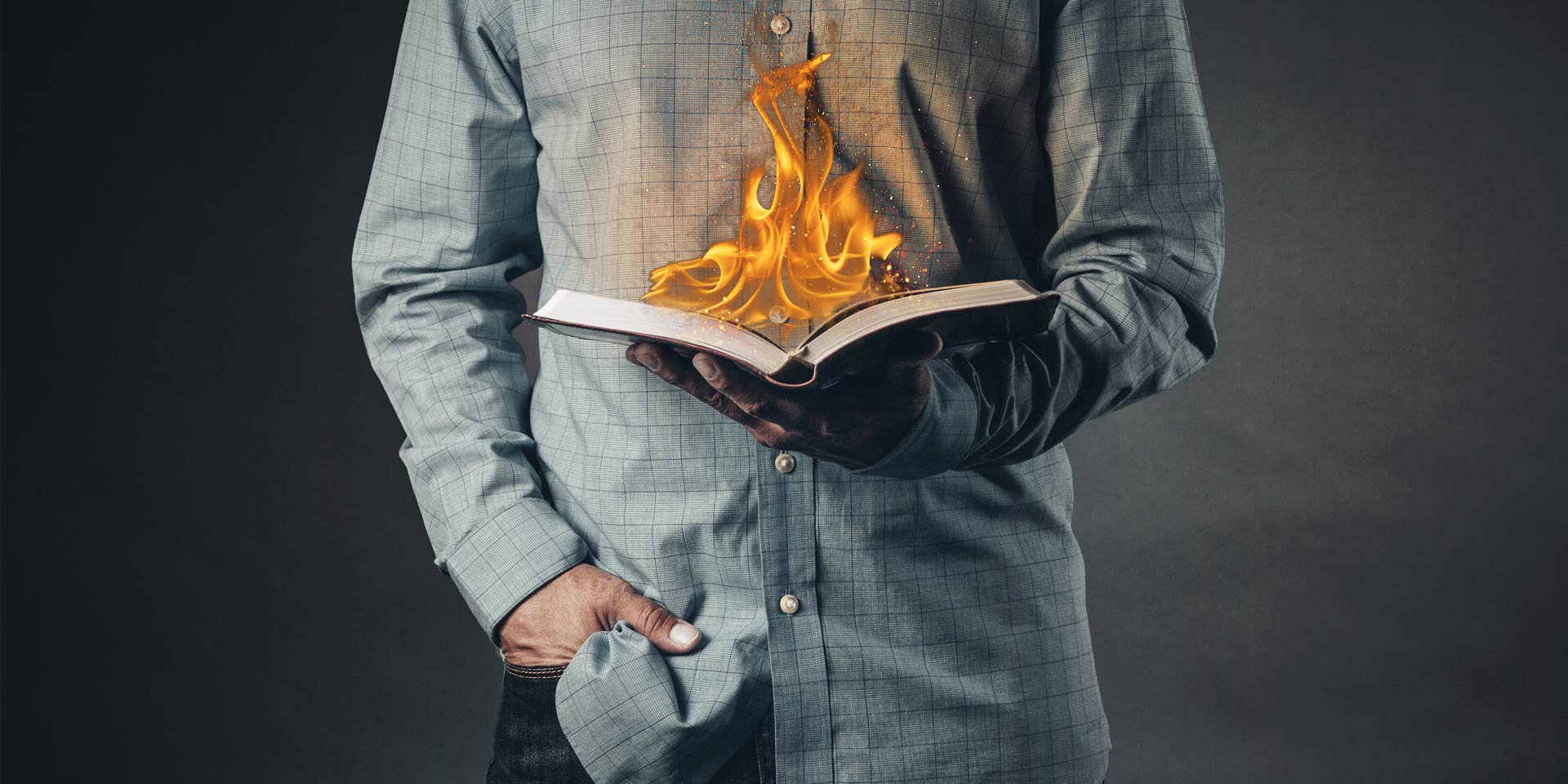

The gesture, devoid of any words, with which he impressed immense crowds of people gathered to see him (some perched in trees, like the tax collector Zacchaeus), was to lift a Bible towards the sky. Surrounded by Securitate agents watching all his moves, in a crowd packed with Securitate “observers,” he offered everyone a magical moment. He raised the Bible from his hand, eliciting enthusiastic applause from the many, quite a few of them anonymous enough not to be interrogated and arrested for their gesture, for their sincere adherence, for their ovations, and tears. It was a gesture that communicated directly with their souls and was worth as much as a sermon: the simple lifting of the Holy Book up high for all to see. The message was unequivocal. It was an urging to keep the faith high, to pray, and persevere in seeking the Almighty. The Bible had become a sign of emerging from darkness, a sign of deliverance.

A sign of offence?

It’s been 33 years since then. The freedom and citizen liberties we enjoy today…seem not to truly bring us joy. Moreover, some citizens from various countries and communities in the free, democratic world appear numb or indifferent to the alarming infringements or restrictions on citizen liberties. Others even advocate for their limitation, in the name of political correctness towards increasingly aggressive and vocal minorities.

Recently, an event that went unnoticed by many illustrates how far intolerance manifested precisely in the name of tolerance and diversity can go. A public sign company in California abandoned displaying an announcement for church meetings after receiving phone protests about the image on the poster: a pastor with a black book in hand. Although the poster had been up for two weeks without causing any disturbance, even though the church later displayed a modified version without the black book in the pastor’s hand (which only suggested it was the Bible, without inscriptions or crosses), even though the calls were complaints or “threats” without legal justification, the company chose to refund the church and not bother those who claimed to be “offended” by the symbol of the Bible.

The author of the article reporting this incident said: “If you needed proof that there is an attack on Christianity, then the conflict over this Bible display is proof.” So, in a country where the banknote reads “In God we trust,” where oaths are sworn in court and at presidential inaugurations on the Bible, it has come to pass that anonymous threats can change social rules and practices. The Bible has become a symbol of public offence.

Judging by the escalating trajectory of such protests with a chance of success, we can expect that in the near future, courtroom oaths will be filmed with a blurred Bible, then that this oath will be abandoned, and subsequently that those who read it or have it at home will be ostracised. Are we not far enough from medieval times when the presence of a Bible at home could lead you to the stake? Wouldn’t it have been right for the representatives of the threatened sign company to file a police complaint for threats and request law enforcement? Wouldn’t it have been appropriate for the representatives of the respective church to publicly protest and demand their rights to be respected, with many other believers joining them as a matter of principle? Only this way can the negative phenomenon of the “spiral of silence” be combated—a phenomenon where the silence of the many, albeit intimidated and discouraged, allows the vocal and reactive minority to impose their point of view on public opinion by manipulating it.

Beyond explanations regarding the manipulation of the masses through the spiral of silence, beyond the predictions of international studies regarding the decline of religiosity globally and the rise of intolerance towards Christianity and evangelism, we should simply ask: Have we grown weary of goodness? Do only societies or generations that have been through a “red desert” value the right to think freely, to say what we believe, to affirm our religious faith?

In the early years following the 1989 revolution, some Romanian intellectuals were invited to Western academic environments to speak about the revolution and life under “communism” (although we referred to it as “socialism,” communism being an ideological utopia projected into a nebulous future). Certainly, televised debates, international conferences, and exchanges of experiences where Christians from the former Eastern Bloc could testify about their lives under dictatorship would be useful once again. Perhaps in this way, that part of the civilised but increasingly radicalised West would understand that their very right to hold a different opinion and orientation is supported by the democratic principles of tolerance based on Christian morality. It is the only functional morality that has made the freedom we enjoy possible, and abandoning it would be akin to cutting down the tree under which we seek shelter from the elements. If the tragic experience, paid with so many human lives and so much suffering, doesn’t help us today to sound the alarm about Western intolerance, which is beginning to resemble that of the dictatorship, then we risk the wheel of history turning. Another escape, this time from democracy, does not appear on the horizon. Because there seems to be no significant difference between condemning a pastor for his pastoral activities in a communist country and condemning him for refusing to officiate a gay marriage in a capitalist country.

It’s downright peculiar that, within a mere 33 years, you come to realise that a gesture as simple as a pastor raising a Bible can either symbolise liberation from darkness and oppression or, conversely, be deemed an “offence” signifying a more subtle and perilous form of suppression. If people choose to relinquish their seemingly natural and effortless religious rights today, they would, in essence, disregard centuries of struggle and sacrifice by believers persecuted for their faith.

It’s only within such a context that we can discern the dark clouds of prophecies foretelling the loss of faith and the Word, the substitution of biblical teachings with convenient surrogates that lead to the demise and death of the soul. The cataclysm that would completely sever us from the divine message would transpire first in dormant, corrupted consciences—what the apostle Paul referred to as the “rebellion.”[2] The revealed Word warns us: “For the time will come when people will not put up with sound doctrine. Instead, to suit their own desires, they will gather around them a great number of teachers to say what their itching ears want to hear.”[3]

It is not only the revealed Word that provides warnings. For those disinterested in biblical prophecy, there are statements from well-intentioned scholars, such as the renowned psychiatrist Professor Doctor Aurel Romilă: “It is fundamental to start from the premise of the existence of another transcendent reality. However, we live in a world (…) where if you utter the name of God, everyone rises against you. (…) I am still a guy who lived for 45 years in socialism. I value freedom. It would horrify me if, under various disguises, we were to lose it again. No matter how much misery, failure, or inferiority there might be, as long as we are free, it’s worth living.”

It would be a display of wisdom to heed these words, rooted in complex experiences and precious due to the pain with which they were earned. Otherwise, perhaps it’s time to clinically label and diagnose a new, peculiar syndrome of our civilization, colloquially known as “growing weary of good.”