This year, Yom Hashoah,[1] or Holocaust Remembrance Day, begins on the evening of April 27th, and ends on April 28th, at sunset. In Israel, entertainment venues are closed from sunset to sunset, sirens sound long, and the six traditional torches are lit, a symbol of the nearly 6 million people who perished in the atrocities of World War II.

The word “holocaust” comes from Greek and means “burnt offering,” a term used to describe the type of Old Testament sacrifices in which the offering was completely burned on the altar. The term continues to be used in this sense in some theological works. For most, however, it describes the extermination of Jews by the Nazi forces, as part of the “final solution to the Jewish question” during World War II.

The Nazis applied the same extermination treatment to Gypsies, homosexuals, people with various disabilities, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Catholic priests, Sabbatarian Christians, and anyone who was proven to oppose the regime imposed on them. According to some historians, the total number of victims reaches 11 million, of which about 60-70 percent are Jews.

The long history of anti-Semitism

The roots of anti-Semitism are old, and the birth of the idea of a nation and the nationalist inclination of the nineteenth century within most European countries caused this smouldering fire to flare into a raging inferno.

It is no secret that many of the Christian church’s liturgical practices, adopted after the first century, in the vein of paganism, were in fact responses to Judaism, borrowed in the name of the idea of being any way, as long as it wasn’t like the Jews. It is for this reason, for example, that most Christians today celebrate Sunday, worship images, or ignore Leviticus’ restrictions on food, arguing that the Sabbath, lack of icons, or clean meat are exclusively Jewish practices, and thus are not recommended to the followers of Jesus Christ and the apostles (who, in fact, were Jews who kept the Sabbath and did not eat “unclean” food).

The anti-Semitic current, born after the destruction of Jerusalem in the year 70, later entered the church and developed over time, often reaching the heights of an imminent disaster. Consequently, in fourteenth-century Europe, the bubonic plague was considered to be spread by the Jews—especially since they recorded fewer deaths than the rest of the population (which was in fact due to the living conditions derived from obedience to Moses’ rules). Over time, the Jews formed strong, fairly financially stable local communities in many states, fostering envy and making them an easy target for those looking for scapegoats for their own infirmities. In addition, the duplicitous and Machiavellian behaviour of some Jews was an additional reason for their rejection.

The spark that ignited the fire of persecution in the twentieth century

Although the nineteenth century witnessed the greatest missionary action of the modern church among the Jews under the leadership of the British Bible Society and its kind-hearted missionaries, the results were not commensurate with the effort. As such, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the interest of evangelical preachers shifted to their parishioners, who were in great need of revival.

At the same time, in Germany, in the 1920s and 1930s, amid the economic crisis and the disaster caused by the loss of World War I, the fact that an insignificant party began to blame the Jews for all the country’s issues did not seem to bother anyone. On the contrary, it propelled the small Nazi party into the circle of the country’s elite politics. From then on, things evolved in small but steady steps.

Thus, on April 7th, 1933, Jewish people were restricted from holding public office or practising law, and then, on April 25th, they lost the right to attend German universities, and a year later were expelled from the military. Between 1933 and 1934 they also lost the right to vote, and they were stripped of their German citizenship and the right to marry their Aryan neighbours. They were even deprived of the right to own cameras, bicycles or typewriters. Finally, traffic restrictions were also enforced. Some saw this as a sign to leave Germany, others remained calm, waiting for these policies to be ended. Those who fled to England or America were luckier than those who only reached Poland or Russia, where the Nazi armies forced them into the same fate as their brothers at home.

On the night of November 9th, 1938, the Nazis organised a pogrom against the Jews in Austria and Germany, known today as the “Night of Broken Glass,” in which synagogues were vandalised, shops were raided, and more than 30,000 Jews were arrested.

After 1939, with the onset of the war, ghettos and then camps appeared. The ghettos were delimited areas of the cities, where the entire Jewish community was moved and separated from the rest of the community. At first, these areas were open, Jews could enter and leave at will, but then the areas were closed with large fences, and the food ration was reduced. From here, people were later loaded into freight cars and told they were being sent to work when in reality, they were being deported to concentration or extermination camps.

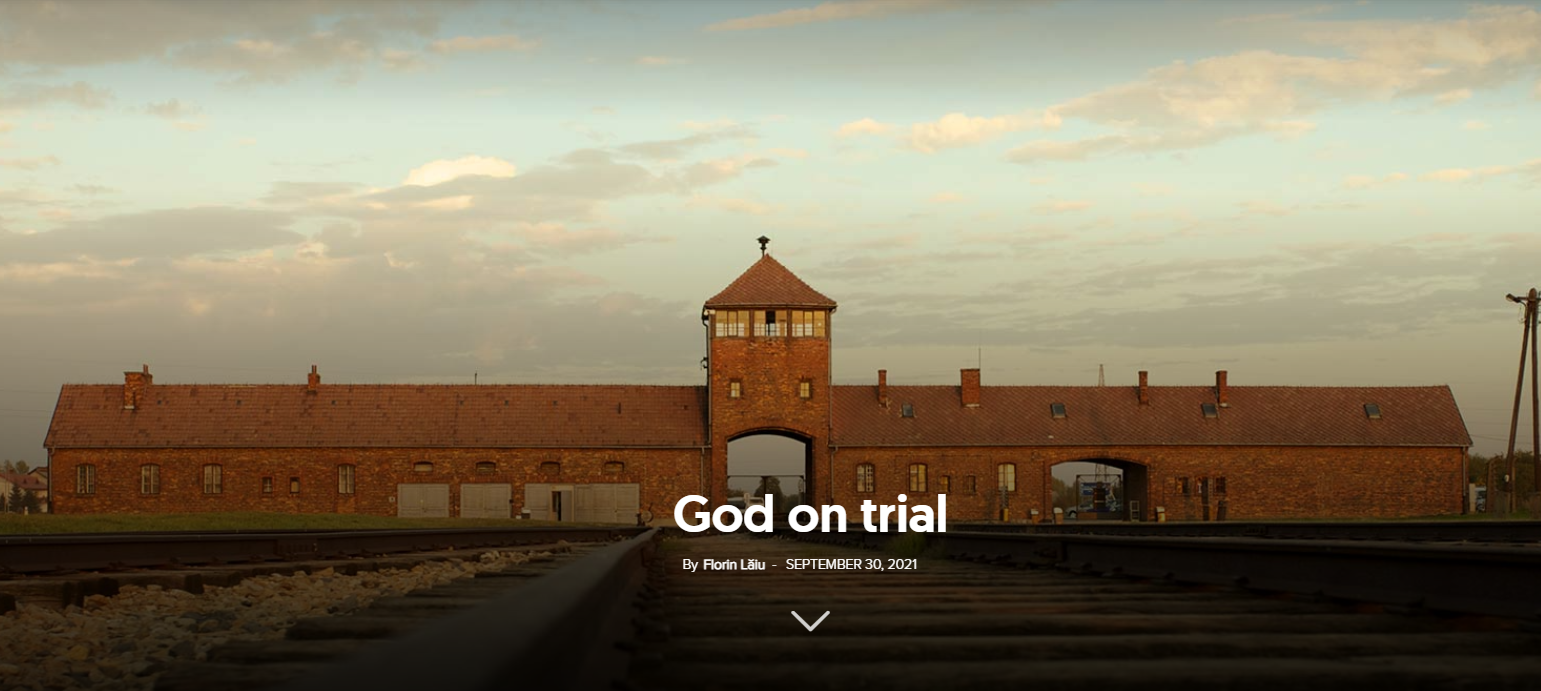

The largest ghetto was in Warsaw, home to an estimated 445,000 Jews. The extermination camps today have resonant names: Chelmno, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Auschwitz, or Majdanek. The largest and most famous is Auschwitz, where more than 1.1 million people were killed by the Nazis. Upon arrival, some prisoners were invited to prepare for a shower, only to be sent into gas chambers and killed. It is estimated that over a million children were killed by Hitler’s soldiers during the Holocaust.

The Holocaust, after almost 80 years

The history of the events of that time leaves us speechless. Less than a hundred years ago, one of the most democratic countries in Christian Europe behaved in the most pagan way possible. The theological justification came at about the same time: “Gott mit uns!”—that is, “God with us.”

Historians today are divided on the causes of the event: was it a predictable or unpredictable outburst, an ordinary episode of history, or a break, an unhappy hiatus, an unrepeatable pause in the complicated score of the times? Such a moment of crisis broke unknown boundaries of the soul, some people bewildering us with acts of unsuspected malice, and others with acts of unimaginable generosity.

At the same time, the Holocaust closed the door on the Enlightenment dream that society was running boldly to its inevitable progress, and convinced us that we were vulnerable to the self-destructive force we had accumulated. Surprisingly, Protestant Germany, or Christian Europe, in general, did not feel the need to react unitedly and in favour of those sentenced to death, either Jews or Gypsies, people with disabilities, homosexuals, or Sabbatarians.

Alan Milchman rightly appreciated, in the prestigious work “New Perspectives on the Holocaust,” that the exterminations in Nazi camps, unlike other similar events in recent history, were based on the advantage of state-of-the-art technology. “In the Holocaust—perhaps for the first time in human history, science and technology, together with their bases in planetary technics, were joined in the effort to totally exterminate the other.”

[2]

Unfortunately, the factors that led to the Holocaust did not all disappear with it, and their cultivation—either for immediate gain, such as an election campaign or for regaining lost popularity—can reopen the flow of much more violent and unexpected events.

Hannah Arendt’s statement is as true as it can be:

“It is in the very nature of things human that every act that has once made its appearance and has been recorded in the history of mankind stays with mankind as a potentiality long after its actuality has become a thing of the past… The particular reasons that speak for the possibility of a repetition of the crimes committed by the Nazis are even more plausible. The frightening coincidence of the modern population explosion with the discovery of technical devices that, through automation, will make large sections of the population ‘superfluous’ even in terms of labour, and that, through nuclear energy, make it possible to deal with this twofold threat by the use of instruments beside which Hitler’s gassing installations look like an evil child’s fumbling toys, should be enough to make us tremble.”[3]

This is obviously not inevitable, and the great individual responsibility cannot be ignored, but recent examples from Ukraine, Congo, Bosnia, the Arab States, and North Korea show us that the apocalyptic predictions are much closer to us today than the dream of democracy has allowed us to believe.

Adrian Neagu is the editorial director of Life and Health Publishing House Romania and holds a PhD in History.