Ask any cinematographer what gets them excited, and I guarantee there’s a fair chance they’ll answer with “lenses”. Having spent many years studying film and many more practising it, I can safely say that I now understand why this is—and it’s probably the first response you’d hear from me if you asked me the same question.

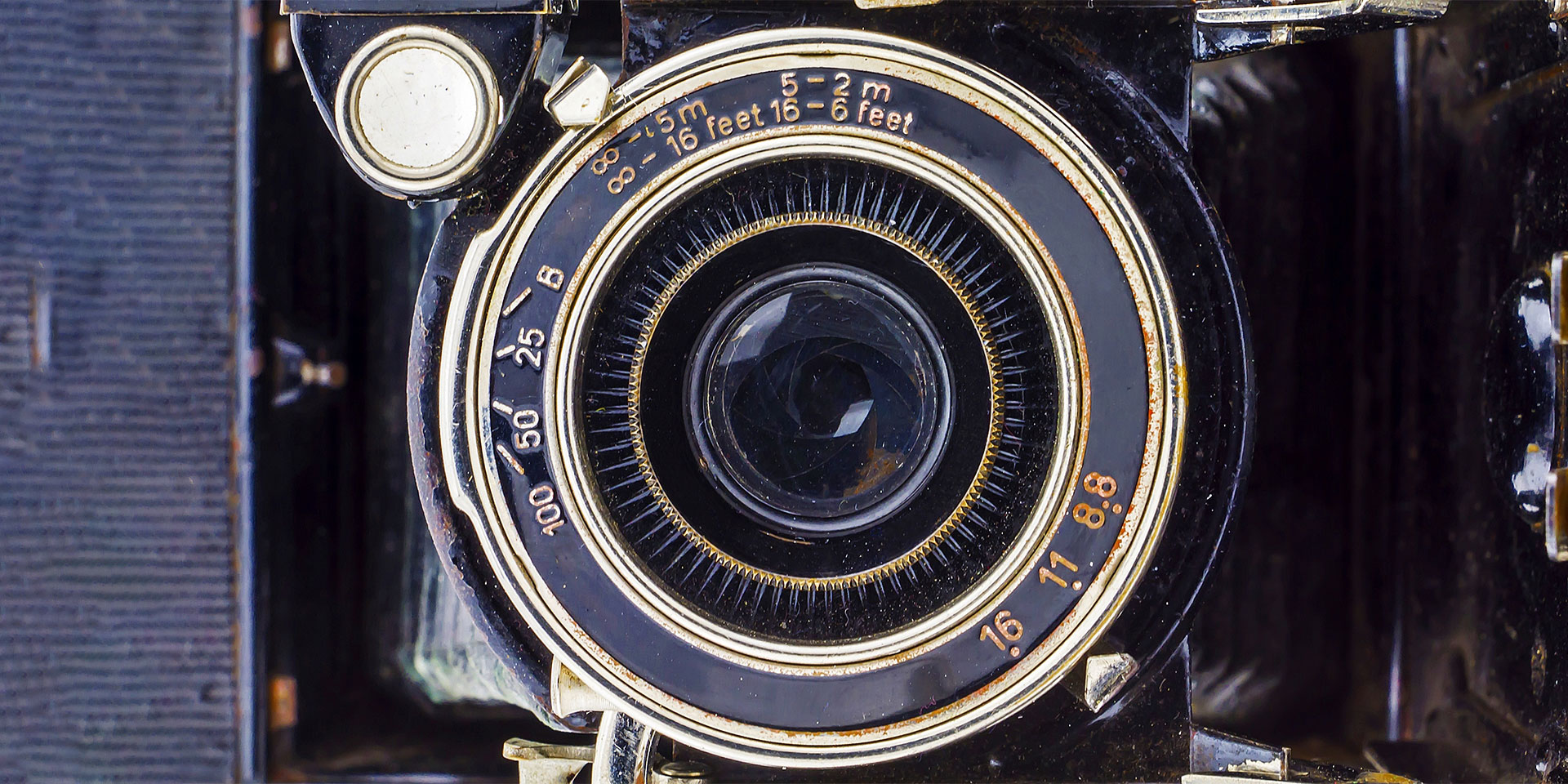

This hasn’t always been the case though. I once perceived a lens as merely a barrel of glass stuck to the front of a camera—the latter being the part that I thought actually counted. If you had asked me about the difference between lenses, and I wouldn’t have been able to tell you. When I bought my first DSLR at a used camera shop in Kent Town, South Australia, it came with a standard kit lens. “That pretty much does everything, right?” I asked the shop keeper. “I guess” he replied with a wry smile.

He couldn’t be more wrong. I soon discovered the limitations of that lens while attempting to take photos during my church’s soccer social. I found that there wasn’t enough light, and when I adjusted the settings to make sure there was, the photos looked rubbish. The ball, the legs and all the bodies running around the pitch seemed to be one blurry mess in each capture. I quizzed a photographer friend about why this was. “It’s probably because your lens isn’t fast enough”, he said.

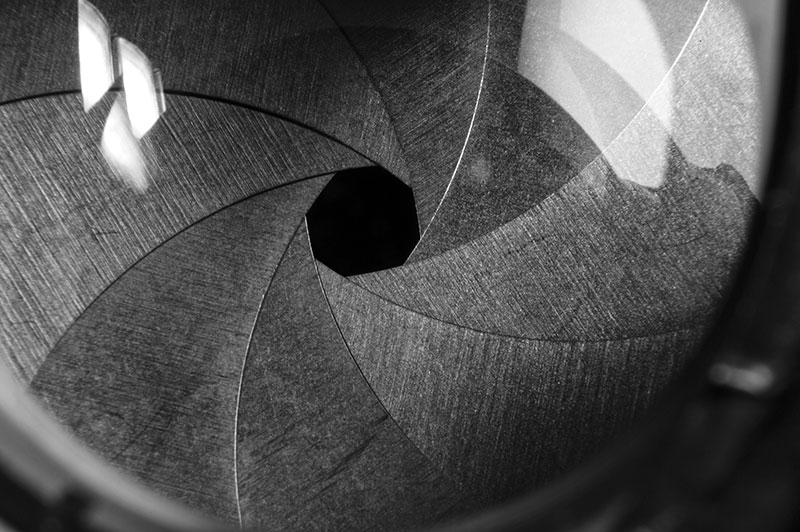

That invaluable piece of information sent me down another rabbit hole—finding the fastest lens I could. I soon realised the lower the f-stop number, the more light the lens would let in.

I felt content for many years with the information and purchases I acquired during this time, until I became fascinated with a new idea. More than just different focal lengths and speeds, lenses can also create footage with a different look. In the world of filmmaking, that unique look can be vitally important.

Rather than looking around for recent lenses that embodied this idea (most of which can cost up to tens of thousands—sometimes for just a single lens!) I instead went back to the past. I’d formed a new obsession—with vintage cinema lenses—housings of glass that were more than 30 years old and had seen and filmed beautiful things.

Check out Signs of the Times’ new short film, shot with 1957 Cooke Kinetal and 1974 Lomo standard speed cinema lenses.

There is something so elemental and special about filming with old lenses. All the things I once thought comprised a bad lens—including flaring and softness—were now qualities that I desired. No longer dependent on autofocus motors within a modern lens, wrangling a manual focusing vintage lens became a labour of love that rewarded the most skilled.

When getting it right, there is no other look like it. It was like looking at the world through old eyes anew.

This started a new craze—finding old cinema lenses being sold for bargain prices where the owner had not realised their value. I found online stories where people had acquired invaluable cinema lenses for cheap prices in places like flea markets. One man in a forum bragged about buying a set of Canon K35 cinema lenses in the early-2000s for less than $A2000. Even one lens out of this ultra-rare brand would nowadays fetch for more than $20,000. One man’s trash really is another man’s treasure.

We could explore the similarities between the human eye and a lens in depth, as they both take in light and colour, but far more interesting is the idea that they change what we see.

How we perceive our environment can be everything. The information that comes through our eye lenses is then processed by our brain (just like a camera). Unlike a camera though, as humans we have a choice with what we’ll do with that information. Will we choose to focus on a person’s flaws—whether that be in character or appearance? Or will we appreciate their beauty? What will we choose to see?

It also begs the question about how the Creator of it all sees the matter—the One who formed everything in front of and behind our perceptive lenses. Genesis 2:7 describes the process of humans being formed by God—“Then the Lord God formed a man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being.”

Unlike a camera system with a focus-puller ensuring the subject remains in focus, God does not control us. He instead allows us to take in the beauty of everything around us and arrive at our own conclusion that He is the Creator. You can imagine the Psalmist David’s euphoria when he realised this: “I praise you because I am fearfully and wonderfully made; your works are wonderful, I know that full well” (Psalm 139:14).

While the seller of the Canon K35’s failed to realise he was in possession of highly valuable glass, God knows the value of what He created in us as human beings. “For we are God’s handiwork, created in Christ Jesus to do good works, which God prepared in advance for us to do” (Ephesians 2:10). God recognises the beauty He created within us, no matter if our lenses are failing or don’t work anymore, right through to the newest and shiniest of lenses.

This article first appeared on Signs of the Times Australia.