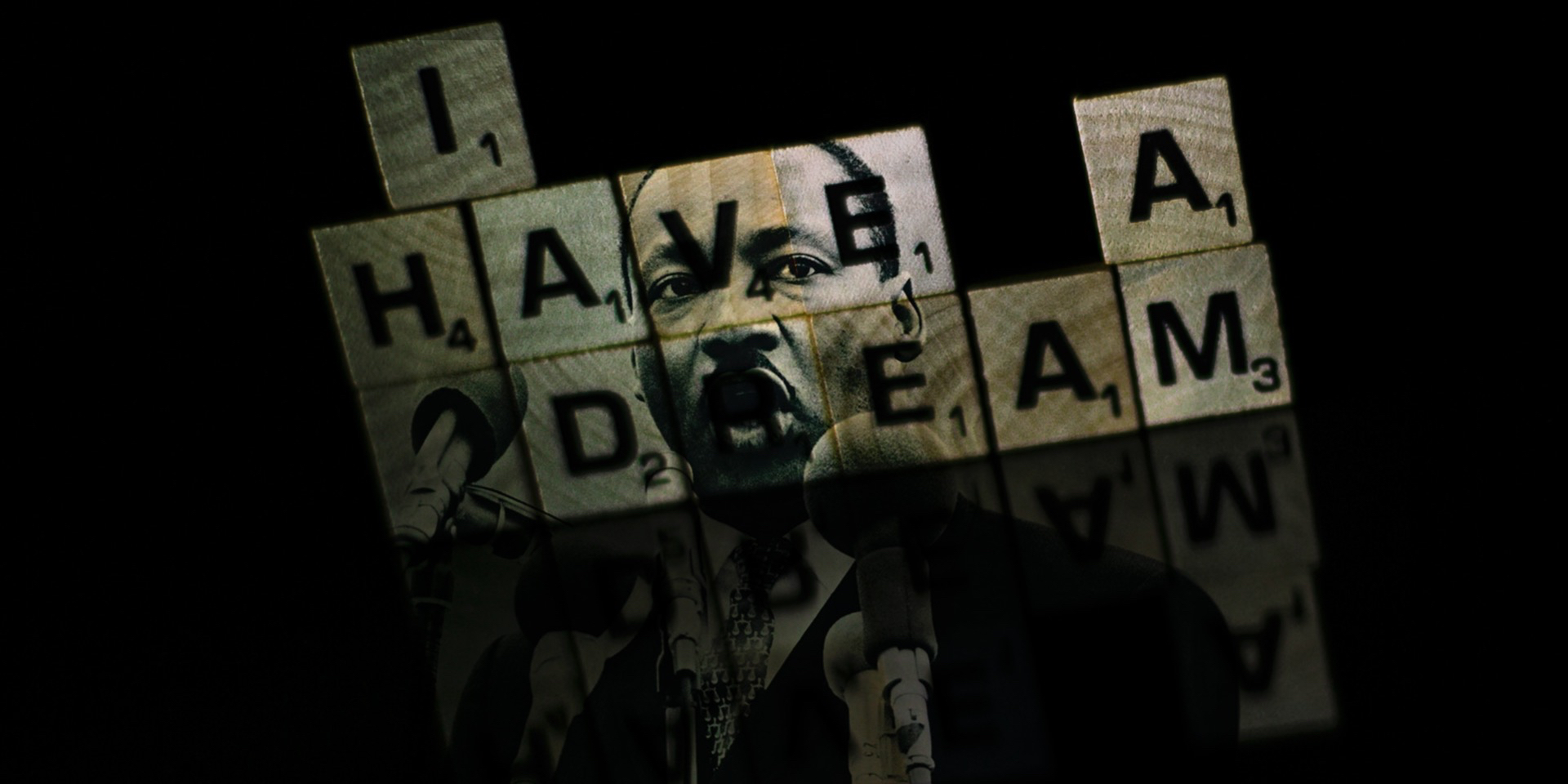

Measuring more than nine metres tall, the pale granite carving of Dr King that is the centrepiece of the Martin Luther King Jr Memorial, just to the east of the National Mall in downtown Washington DC, makes it easy to forget that he was a relatively short man. His iconic likeness towers over visitors as his words carved into the stone walls around the site preserve his prophetic voice.

Situated in a direct line of sight between the Lincoln Memorial—from whose steps he delivered his famous 17-minute “I have a dream” speech to the crowds assembled for the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom” on August 28, 1963—and the Jefferson Memorial on the other side of the Tidal Basin, it is easy to forget that Dr Martin Luther King Jr was not universally admired in his lifetime. Instead, he was often described as a troublemaker, an agitator and possibly “a communist.” That he would be honoured in this way—in addition to the transformation of King’s birthday into the national holiday of Martin Luther King Jr Day—less than 45 years after his assassination in Memphis on April 4, 1968, would have seemed unlikely at that time, to both his critics and his supporters.

But the growing reverence for Martin Luther King Jr, as an iconic leader of the Civil Rights Movement in the United State in the 1950s and ’60s and a global voice for justice, in the decades since his death has come at the cost of forgetting—or diminishing—some key aspects of his life, his work and his voice. Visiting the Martin Luther King Jr National Historical Park—covering a few city blocks in an older neighbourhood just to the northeast of downtown Atlanta, Georgia—offers some important reminders.

The first thing we need to remember to understand the work of Dr King—both for racial equality and otherwise—is that it was grounded in the Black church. With both its contemporary and historical buildings on the National Park site, the Ebenezer Baptist Church was the church in which Dr King was raised and the church he eventually pastored, as had his father and grandfather before him. And this faith was the foundation for his work for justice.

Just to the east along Auburn Avenue is the house in which Dr King was born and raised by his father and mother. Specifically, he was born there because his parents refused to accept the segregated and substandard hospital facilities available to Black people, so even the place of his birth was an act of resistance. Dr King’s father visited Germany in the early 1930s, both visiting historical places of the Reformation and witnessing firsthand the beginnings of the rise of Nazism, and was so affected by the experience that he changed his name and that of his then-five-year-old son to “Martin Luther.”

About 20 years later, in Montgomery, Alabama, Dr King would start a new reformation. As a newly-arrived young pastor, he was elected as leader of the Montgomery Improvement Association, which was primarily a coalition of Black churches who were supporting a boycott of the city’s bus system in protest against the laws and practices of racial segregation. There were pragmatic reasons for the churches’ leadership in this protest movement: the churches were the natural social and organising networks for the Black community, and the clergymen were often the only members of the community who were not employed by white people and so were not risking their employment by speaking up on these issues. But the Black churches also provided the theological insights and the spiritual inspiration that would be the foundation for the Civil Rights Movement. It was a religious movement as much as it was social and political. The many religious leaders—black and white, priests and rabbis, pastors and students—who joined various of the protests was evidence of this.

And this was as true for Dr King personally as it was for the movement as a whole. His prominence as a young leader caused him to become the target of those opposing the boycott action. This peaked at about midnight, in early 1956, when he received an anonymous phone call threatening—with additional racial epithets and expletives—that “if you aren’t out of this town within three days, we’re going to blow your brains out, and blow up your house.”[1]

Understandably, Dr King was upset after receiving this call and, while his young family slept, he sat in their kitchen wondering what he should do next. He battled with his fear and the conflict between what he saw as his duty to the cause in which he had become involved and his duty to his family. In Dr King’s own words: “And I discovered then that religion had to become real to me, and I had to know God for myself. . . . And it seemed to me at that moment that I could hear an inner voice saying to me, ‘Martin Luther, stand up for righteousness. Stand up for justice. Stand up for truth. And lo I will be with you, even unto the end of the world.’”

Dr King found great strength from this experience: “Almost at once my fears began to go. My uncertainty disappeared.” Three days later, his house was bombed and a crowd gathered, wanting to respond with violence. But speaking from this foundation of faith in the presence of God, he urged the crowd to continue to protest with non-violence.

Much of what we know as the Civil Rights Movement and of the protests that marked it were focused on desegregation and voting rights for Black people in the American South. These seemed to climax in the March on Washington, the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Selma to Montgomery marches in March 1965, which caught national and international attention.

But, writing in 1967, Dr King noted a significant shift in the nature of his ongoing work. His focus was turning to larger issues of racism, poverty and militarism across the United States and in the world beyond. He recognised that these campaigns were more difficult because the legal standing of their claims were not as clear. Instead of focusing narrowly on the civil and constitutional rights that were somewhat recognised in the existing laws of the United States, he reflected, “We are entering the area of human rights.”[2]

Awarded as the then-youngest-ever recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, Dr King embraced a broader view of the work for justice in the world. His later campaigns and particularly the last book that he wrote—Where Do We Go From Here?—included increasing engagement with issues of economic justice, anti-militarism, and community, national and international wellbeing.

But this was to be an incomplete work. It is easy to forget that he was killed at just 39 years of age. King’s death is a tragedy which continues to resonate today, a life cut tragically short in the midst of his work. With his wife Coretta Scott King, his tomb is part of the National Historical Park on the block between the house in which he was born and the church in which he preached. The visitor centre continues to tell the story, to celebrate the achievements of the Civil Rights Movement—how things have changed—and to urge visitors to the ongoing work—recognising how, in many ways, racial injustices and inequities have not disappeared.

Dr King saw that the achievements of the Civil Rights Movement would need to be defended and the work of justice would be perennial. He recognised the persistence of “unregenerate segregationists who have declared that democracy is not worth having if it involves equality,” instead seeking the “total reversal of all reforms, with reestablishment of naked oppression and if need be a native form of facism.”[3]

The words carved in stone at the Martin Luther King Jr Memorial remain inspiring, which is why many of them become social media posts in response to news stories from time to time. But for most of us, we live with the tension Dr King identified: “…uneasy with injustice but unwilling yet to pay a significant price to eradicate it.”[4]

This makes Dr King’s resounding voice all the more important to hear again. And the foundations of his life, faith and prophetic call too important to forget.

Nathan Brown is book editor at Signs Publishing Company in Warburton, Victoria. A version of this article first appeared on the Signs of the Times Australia/New Zealand website and is republished with permission.