Mass evangelism “campaigns” have become a common phenomenon in contemporary religious culture. However, few people ask how it all started and what are its long-term effects.

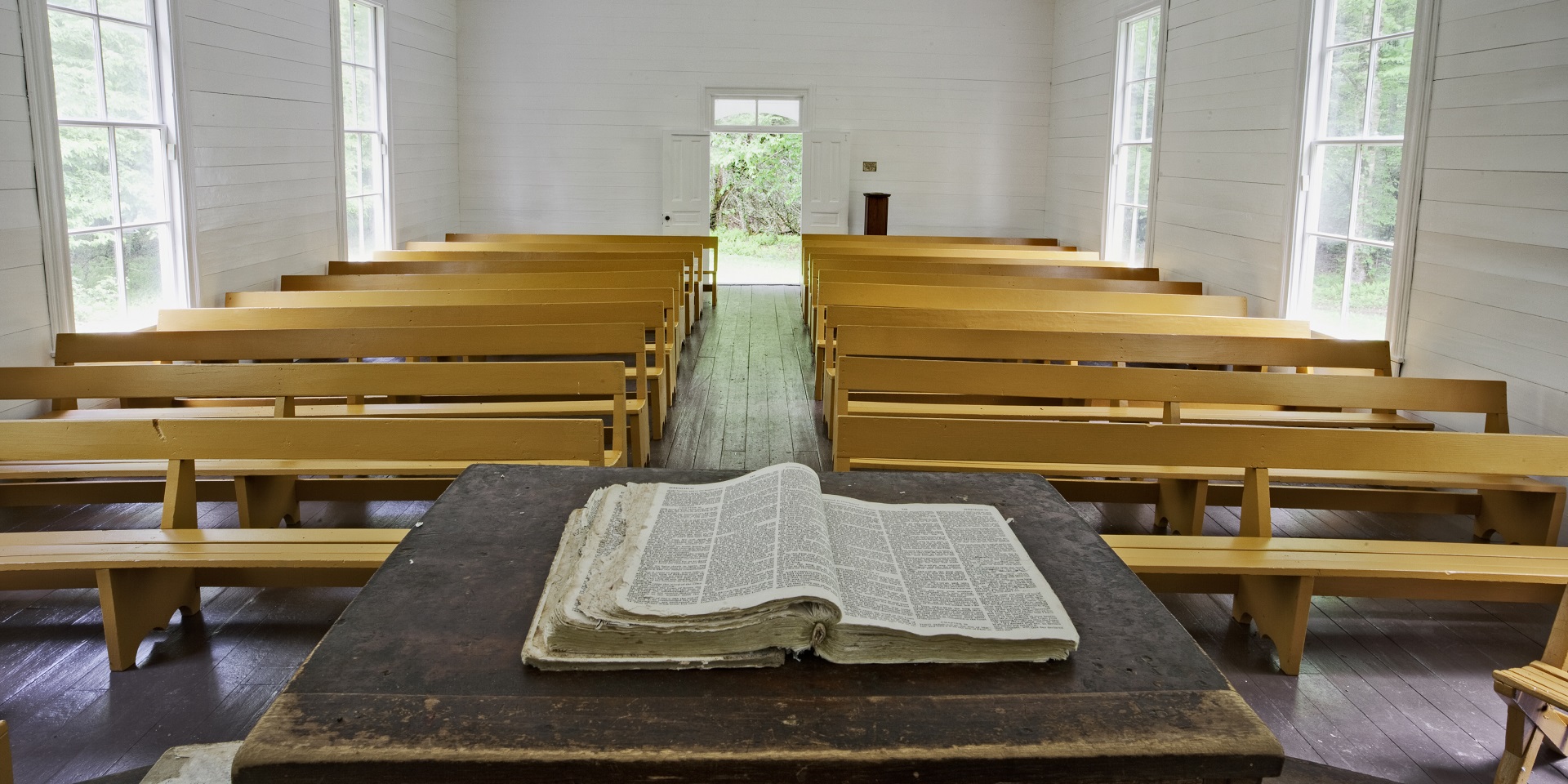

Around 1825, a new preacher arrived in Evans Mills—a small American town on the border with Canada. With less than 500 inhabitants, the town did not have a church, only the stone schoolhouse, where the Congregationalists and Baptists gathered together. Charles Finney preached here.

Finney had noted the deplorable behaviour of the inhabitants: the streets resounded with arguments, swearing, and cursing. On one occasion, Finney ended his sermon by warning them that he would leave unless they were willing to publicly show that they accepted or rejected Christ. When he asked them to stand up, as a sign of accepting Christ, or sit down, as a sign of rejecting Him, the people were dumbfounded. No preacher had ever asked them that. They got up angrily and left the hall. Thus began the story of the one who would be called “the father of the modern revival movement”, a major influence on later mass evangelism.

From law to the “burned-over district”

Finney converted in his law office, reading the Bible to understand texts inserted into law books and frequently quoted by older lawyers. Devoting himself to preaching, he realised that, however logical and convincing, his arguments could not move the stubborn will of the unconverted. So, he began to pray persistently to God and address the emotional side of people. Conversions multiplied and the fire of revival spread throughout upstate New York, which came to be known as the “burned-over district”. The spirit of revival also spread to other states, and went down in history as the Second Great American Awakening.

The Second Great Awakening

This movement had a major impact on American religious history, involving millions of people, leading to the numerical growth of existing denominations and the emergence of new ones, by proclaiming the message of the second coming of Jesus Christ. The most prominent example is the Advent movement, which began in the 1830s and which led to the emergence of the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

At the same time, it had a major impact on American society through the reforms it generated in the fields of temperance, women’s rights, and abolitionism. Through the theology and influence of Charles Finney and other leaders, local churches became aware of their role in society, striving to ennoble the world through the message of salvation, through changes in laws, and the creation of new institutions.

Charles Finney’s methods

Finney’s evangelistic approach was deeply rooted in his theology. He claimed that people have a totally fallen nature and that they are saved by grace, through faith alone. He saw works as a proof of faith. At the same time, he was a perfectionist, affirming that the individual has free will, which he or she can use for good or bad.

This explains the major influence he had on social and political changes in 19th-century America. He supported women’s rights and campaigned for the abolition of slavery, urging his converts to support this cause by voting and getting involved in the political struggle.

The thing for which he was both most admired and criticised was the pragmatism with which he approached evangelistic preaching: “Perhaps the most lasting element that Finney unwittingly contributed to contemporary Christianity was pragmatism”.[1] For instance, from the Methodists he took over the “Mourner’s Bench”[2] and the “camp meetings.”[3]

Later, he began to call people to kneel before the platform to receive Christ. In preaching, Finney used an improvised style, often disapproving and publicly criticising individuals. Through his musical talent, with his imposing stature (he was 1.90 metres tall), piercing eyes, and innate leadership skills, he awakened in his listeners the desire to become true Christians, being considered “the most influential liturgical reformer in American history.”[4]

Echoes in contemporary Protestantism

Charles Finney’s pragmatism was popularised and disseminated in the Protestant mentality through his book, Lectures on Revival (1835). Promoters of modern revivals borrowed his methods and elevated them to the rank of norms, as can be seen at almost every level of preaching—from parochial preachers to contemporary mainstream evangelists.

Calling people to the front for “special prayer”, asking them to stand up or to raise their right hand as a sign of “surrender”, filling out sign-up sheets—all against the background of singing special hymns by the choir or soloists—drew criticism from opponents, on the grounds that they are a form of psychological manipulation.

Thus, the Protestant idea that any teaching must be verified against the Bible before being accepted was contradicted by practice, where almost anything was accepted as long as the result was “winning souls.” However, an even more important “side effect” was the establishment of the individualistic spirit in Protestant Christianity (“salvation is personal”), to the detriment of the mutual edification of the “laity” and their involvement in the proclamation of the Gospel.

This harmful effect was brought upon Protestantism by its very preachers, who, in their desire to have the same success as Finney, became the dominant attraction of the church, transforming, in its turn, into a meeting-place of individualities. The danger had been sensed by one of the most famous revival preachers during the First Great Awakening, John Wesley: “Christianity is essentially a social religion, to turn it into a solitary religion is indeed to destroy it.”[5] Clearly, Finney did not take such a thing into consideration.