The separation between church and state is celebrated by those who appreciate freedom of conscience. However, this separation can also have less fortunate ramifications.

This separation is, at the same time, a generous and a vague notion. To understand it we need to answer at least a few questions: what does “church” mean, what does “state” mean, and, finally, must all or only some church/religious aspects be separated from the civil state?[1]

If we were to consider the attitude of the European Union towards Christianity, we would notice that this is “marked by ambiguity, compromises, and liberalism”.[2] Europe denies its Christian roots, and Christianity is seen as old-fashioned and irrelevant. The Christian Church, for its part, is not always sure of its role in the state, and segregationist tendencies are always lurking, either for theological reasons, or reasons of identity.

No matter what denomination one identifies with, these concerns apply to anyone who considers themselves religious, particularly Christian. Ultimately, Jesus prayed for His followers, “My prayer is not that you take them out of the world but that you protect them from the evil one” (John 17:15). Both before and after this Bible verse, Jesus insists that those who follow Him “are not of the world” (John 17:14-16), even though they are sent “into the world” on a mission. Therefore, “there are two limiting tendencies that must be avoided: the total historicization of the Church and the sacralization of the state”.[3]

Being in the world, not of it and yet for it, is not an easy thing to comprehend and especially not an easy thing to achieve. Here, however, we find the essence of what the church should be in the state. In this article we will look at some of the models Christianity embraced when trying to fulfil its mission in the world.

The theocratic model

Those states whose political-administrative organization overlaps with “God’s governance” are called theocratic, as the etymology of the term suggests. In ancient times, the distance between religion and the state was almost non-existent (see: ancient peoples such as Egypt, Israel, or empires such as Babylon, Medo-Persia, or Rome). In today’s world, theocracy is present exclusively in several Middle Eastern states, all of which practice the Muslim religion.[4]

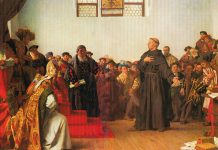

One of the most famous Christian attempts at theocratic rule was Geneva in 1555-1564, the third and most prosperous period in which John Calvin was present in this state-city and had an undisputed influence. Calvin’s view that God is sovereign over all aspects of life made him see no distinction between religion and the state. For him, everything was religion.[5]

Thus, laws formulated in support of purging society of its vices invaded the public life in Geneva, and religion began to dictate, to restrict, and, if necessary, to punish. (Suffice it to mention the law banning the celebration of Christmas, which came into force in 1550.)

Calvin’s radical tendencies ruled for a time in Geneva even after his death and reached even England and Scotland, the latter under the influence of the reformer John Knox. At the end of the 16th century and in the first part of the 17th century, Presbyterian England was about to turn London into a second Geneva. The city’s leadership was in favour of the strict observance of Sunday, which was theologically confused with the Sabbath of the fourth commandment (that is, Saturday), and an almost Pharisaic strictness was imposed on Londoners.

Dance scenes, bowling alleys, and taverns were haunted in search of Sabbath-breakers. While entertainment that went against piety was forbidden, church attendance was mandatory, and from the pews, Londoners would hear sermons about a harsh love that would punish any transgression, then and there or in the future.[6]

Later, however, such radical tendencies made society tired. They also aroused adverse reactions, and eventually faded. People understood that Protestant radicalism was no better than the medieval Catholic Inquisition. The church must not subjugate society, but win it over.

Today we have state churches (in England, and the Nordic countries) and national churches (in Greece). These are the closest to the old theocratic model. However, state-church intertwining is rather a formality, as there are no legislative intrusions in the field of religious practice. In such a climate, the church will tend to have an institutional influence on society, not a spiritual one, and the mission of the church will be in tune with the political platform of the state governing bodies.

The monastic model

At the opposite end of the spectrum is the monastic model. Alongside the churches which harbour monastic orders (mainly Orthodoxy and Catholicism) we also take into account all those tendencies of total separation between church and state. In the early centuries of Christianity, the Christian mission was considered to be imitating Christ in society. Given the hardships and persecutions the church was subjected to, the best way to perform imitatio Christi was martyrdom. However, after the Roman Empire became Christian, the imitation of Christ through supreme sacrifice was no longer possible.

Deprivations had to be self-imposed, and the setting in which they could best happen was the hermitic one.[7] This was a bloodless form of martyrdom, meant to produce living examples of what it meant to live for Christ in the world. Whether or not they succeeded is difficult to say, but the monks’ contributions to societal development are worthy of attention. Many monks copied classical manuscripts, and built roads and buildings (churches, schools), thus developing art, architecture, and music—in a nutshell, Western culture.

The isolationist attitude of the church also came from the state. The most systematic limitation of the Christian church was ushered in by the French Revolution. As a result of the provisions of the secularization of political life in 1789, the church would no longer be funded by the state, religious staff could not have a social or political rank, theological study would be done in private, and access to religion in public schools would be limited.[8] Under such conditions, the church was literally isolated from society, and the latter, unlike in antiquity, did not require and did not expect the contribution of the church to the welfare of society.

The cooperation model

There is also an intermediary model, used in Latin countries (Italy, Spain, Portugal, Romania) and Germanic countries (Germany, Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg). In these countries, the state and the church are separate, but maintain a collaborative relationship. Thus, while not dictating or favouring a particular church, the state expects the church to get involved in assisting the army, prisons, hospitals, and even schools. Religious leaders should not be involved in politics,[9] but neither should they be inactive or indifferent to the needs of society.

In such a context, the church can take full advantage of the state’s willingness to support actions that it sees as compatible with the church’s mission. The other side of the coin is where the church believes that working in cooperation with the state conflicts with its mission and leads to an even deeper secularization of the church. Out of the models presented above, this one is preferable.

In the last part of the article, I will present the Christic model, but not as an alternative model (ultimately, the Jewish society of two thousand years ago cannot resemble today’s societies), but as an inspiring one, from which the church (because these reflections are addressed to it) can learn and find the guidance needed to fulfil its purpose.

The Christic model

If the Christian mission is to “reproduce” Christ in society, then looking at Christ Himself is imperative. First of all, being interested in what people think about you is fundamental. Christ was interested in the public opinion about His identity (Mark 8:27). The church must do the same, and if it finds out that it is unknown to the public (in the case of minorities) it should be worried. It’s worse not to be known at all than to have people have true or false opinions about you.

Prior to this search, of course, the church would have done something remarkable, useful, and relatively easy to notice. Second, Christ knew His generation. How else could He have provided such a piercing review as the one in Matthew 11:16-19?

In this passage, Christ says of His contemporaries: “They are like children sitting in the marketplaces and calling out to others: ‘We played the pipe for you, and you did not dance; we sang a dirge, and you did not mourn.’ For John came neither eating nor drinking, and they say, ‘He has a demon.’ The Son of Man came eating and drinking, and they say, ‘Here is a glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners.’”

This text contains the third principle: such things as a healthy, non-aggressive radicalism (John the Baptist) and an uncompromising friendship with sinners (Jesus) do exist. Both are paradigms of a healthy influence of the church on the “city”.

The prophet John the Baptist preached in the wilderness of Judea, on the banks of the Jordan River. There he preached a message that might sound radical, but ultimately demanded the normal: those who have should share with those who do not; the tax collectors must not ask for more than they are owed; the soldiers must be satisfied with their salaries and not extort money by threats and injustice (Luke 3:11-14). He was heard and believed by tax collectors and prostitutes, but rejected by priests and rulers (Matthew 21:32).

However, John was not a hermit. In Mark 6:20 we are told that King Herod “was greatly puzzled; yet he liked to listen to him”. A king wouldn’t have gone into the wilderness to listen to a prophet, which means that John must also have preached in Jerusalem, where the king would have had the opportunity to listen to him. Moreover, John addresses Herod directly and condemns his marriage to his sister-in-law, which was not allowed according to Judeo-Christian values (Mark 6:17-18).

Succeeding in reaching people from so many different social categories (from prostitutes to kings), the example of John the Baptist illustrates what the church should be from a moral point of view: the proponent of a clear worldview that knows how to distinguish good from evil and proclaims this distinction without discrimination.

Jesus, on the other hand, is the Prince of peace. He is the one who came to bring the good news of salvation. From His baptism to His crucifixion, His feet were tireless in carrying the same message as John the Baptist, albeit with a different approach. His healings, good works, forgiveness, and education of the masses were the gifts by which He introduced Himself to the people. These are probably the main ways in which the Christian church should serve society. Neither Jesus nor John the Baptist were part of the political leadership of the time, but their influence penetrated the upper reaches of society. They worked for both the masses and those responsible for the well-being of the masses.

In conclusion, the church is not of the world, but is in the world, and with a mission. This mission encompasses all walks of life, is sharp in the way it identifies the real needs of society, and tireless in meeting those needs. Today, another environment has been added that did not exist in the past: the online world. As far as the examples of Jesus and John are concerned, the church that wants to imitate Christ should be present in the online environment too, not in a corner of inobservance, but in a position where its voice can be heard.