One of the surprises of the twentieth century when it comes to religious freedom was Dignitatis Humanae Persona, the first declaration of religious freedom officially promulgated by the Roman Catholic Church in 1965, at the end of the Second Vatican Council.[1]

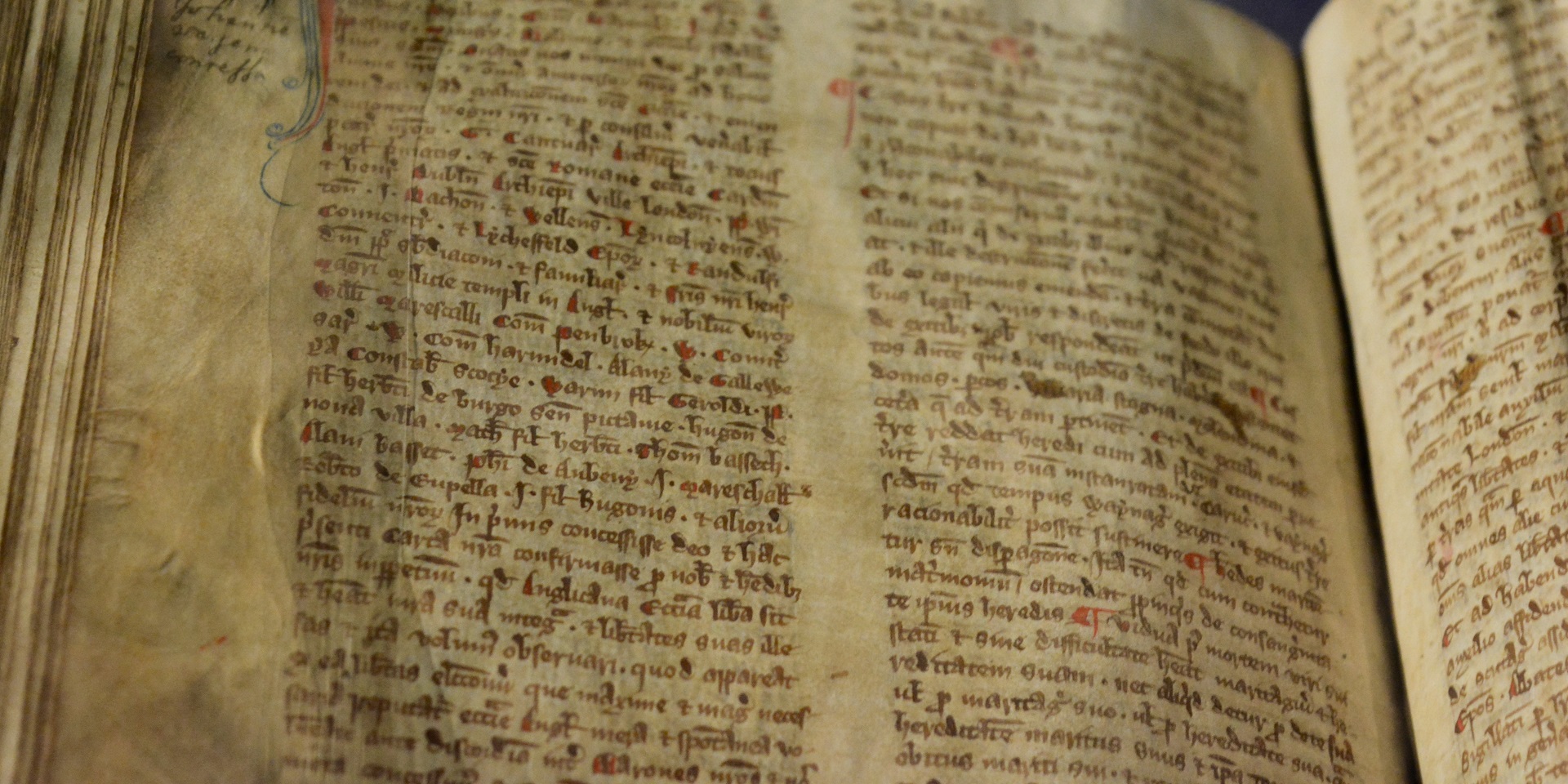

The surprise lies in that the past of the Catholic Church cannot be considered eminently tolerant. Beginning with the 12th century, heresy was criminalised in Gratian’s Decree (around 1140), heretics being considered traitors to God by Pope Innocent III (1199). With the enactment of Canon 3, On heretics, at the Fourth Lateran Council (1215), persecution of heretics began with groups such as the Waldenses and Albigenses (Cathars) of northern Italy and southern France.[2]

The definition of heretics and heresy was sprinkled with quotations from Augustine.[3] “No author, Christian or secular, was more widely read in the West throughout the Middle Ages than Augustine”.[4] However, his message was reinterpreted, given new meaning as it intersected with the theology of the time, a fact very well illustrated by the texts of the most important mediaeval theologian, Thomas Aquinas (ca. 1225-1274). His philosophical-religious system, known as Thomism, accurately illustrates the understanding of the Middle Ages in matters of religious freedom.

The epitome of Middle Ages Catholicism

Thomas was born in the family castle of Roccasecca, Italy, and at about five years of age, was taken by his parents to the Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino to become a monk.[5] Here the foundations of the knowledge of the Bible were laid, but also those of the writings of Augustine and Gregory the Great (around 540-604). From the age of 15, Thomas continued his studies in Naples, where he became acquainted with the philosophy of Aristotle through Avicenna (980-1037) and Averroes (1126-1198),[6] as well as with the Jewish writings through Maimonides (1135-1204).

It is also there where, despite his family’s attempts to stop him, Thomas joined the Dominican order. He later studied under Albert the Great (around 1200-1280) in Paris and Cologne (1245-1252). In 1256 he began teaching theology in Paris and began writing one of his important works, Summa contra Gentiles. A few years later (1265), sent to Rome to establish a Dominican school, Thomas began to write his most important work, Summa Theologica, a synthesis of Christian theology with Aristotelian philosophy.

Thomas is convinced that only “those actions are properly called human which proceed from a deliberate will”.[7] The human will tends to a single ultimate goal,[8] which is identified with the happiness that lies in union with its Creator.[9] That is why, for Thomas, unbelief is the greatest sin, for it contains aversion and separation from God.[10] All who deviate voluntarily from the teachings established by the authority of the church, expressed primarily by the “supreme pontiff,” are considered heretics,[11] as the Cathars were perceived, and against whom certain arguments in the Summa Theologica are directed.[12]

Thomas argues that those “who at one time received the [Roman Catholic] faith and publicly professed it (…) must be compelled, even physically, to fulfil what they have promised and keep faithfully what they once received”.[13]

The reason, Thomas explains, is that while the acceptance of faith is an act of the will, keeping it “is a matter of necessity”.[14] Thus, the falsification of the faith must be punished by the excommunication of heretics, and in some cases, they must be “justly put to death” [15] by secular authorities.

Based on the Bible passages from Titus 3:10-11 and Matthew 5:44, Thomas argues that the church can accept penitent heretics by showing concern for their spiritual good. But this good is not identical with the bodily good, which is only temporal and often in opposition to the spiritual one. Thus, Thomas continues, when those welcomed back fall into heresy for the second time, this is a sign of their inconsistency when it comes to faith. And so those who return again are received in repentance, but not so as to be saved from the death penalty.[16]

Distances and shades

He creates a taxonomy of unbelief according to which the unbelief of the Gentiles is less serious than that of the Jews, and that of the Jews is less serious than that of the heretics.[17] In the Thomist view, pagans and Jews “should in no way be compelled to accept the faith”,[18] because faith is a personal choice, unless the coercion is made in order to promote the spread of Christianity.

Thomas argues that pagan rites can be tolerated “either to promote some good or avoid some evil”.[19] The good that Thomas refers to is the possibility of converting pagans to Christianity, and the evil to be avoided is the potential misunderstandings that may arise. The premise of community order based on natural law is the basis for accepting the rites of the Jews, which must be tolerated because they foreshadow Christian truth.[20]

Although Thomas approves and even encourages the death penalty for heretics, he is more tolerant of pagans or Jews.

The above-mentioned Thomist arguments seem to be designed to justify the practice of the church and its compatibility with the gospel message, in a society where the boundary between civil and religious power was not very visible.[21] Even the Dominican order, of which Thomas was a member, had been set up to combat the teachings of the Albigenses.[22] Thus it can be said that “the modern idea of religious freedom was completely alien to his thought”.[23]

From the perspective of Dignitatis Humanae Persona, Thomas Aquinas promotes a religious freedom with limited applicability, with restrictions on certain groups of people.[24] Nevertheless, the emphasis on natural law and the resulting community order had an influence that went beyond that envisaged by Thomas, contributing to the development of the concept of civil authority independent of the religious one.[25]