“Religion is what is in my soul. No one can take away what is there. But in public we have to comply…”

During the communist rule, I had some problems at school because of the conflict between my system of thinking and their system. On the Lord’s Day, I was absent from school and went to church, obeying God’s commandment.

I believed in God and the creation of the world, while the system believed in the uncreation or transformation of the world. One of the things we had to do was pretend not to believe. I was told this more than once: “Florin, I have a religion too, but it’s in my heart. Nobody can take that away from me. But in public we have to comply…”

I mean, you can be Mother Teresa in your soul, but in public you have to behave like a normal person, according to worldly standards. Is this the wisdom of moderation and modesty, as it seems, or is it just another myth?

Inner religion or insignificant religion?

Admittedly, more odious is the other form of hypocrisy, which puts religion on display while the soul is empty and haunted by motives completely alien to the spirit of religion. These are religions that implicitly promote formalism.

The mere performance of certain gestures, the observance of certain rules, becomes salvific. However, we don’t judge anyone’s motivation. Does it bother us if he takes out his mat and kneels in the street because it is prayer time? That she says grace before eating in a restaurant? That he makes the sign of the cross as he passes significant places or at important moments? That she politely refuses the chocolate we offer her because it is Lent? That he doesn’t work today because it’s a holy day?

Reasonable people understand that true religion is a religion of the soul; that is, it comes from the soul, it is not pretended.

But the myth is that religion is only for the inside. “Keep it to yourself, don’t let everyone know and stumble over your religious obligations!” Should we think of religion as being as intimate as sex, which is not made public? Could it be that the real motivation behind this sentiment is shame about one’s religion?

Perhaps the religion we have is only a cultural inheritance and we do not have personal convictions that allow us to express with serenity in word and deed what we believe, because in reality we do not really believe.

Faith and religion are words that are sometimes used synonymously.

But while faith is primarily in the soul, religion is an externalisation. It has a historical and social existence: we belong to a religious community, we have religious traditions, we have religious obligations that we have inherited or freely taken on. Religion without a ‘cult’ (that is, a community of believers) is unlikely to last.

“Without cult” often means uncultured in the literal sense of the word: uncultivated, unrefined, untended. But religion builds not only a cult, but a culture. Civilizations and peoples owe their culture to a large extent to divine worship and religious cultivation.

God, a reality of life and death

To the extent that one’s religion is true—that is, based on faith and morally relevant—it will express itself. Religion has public demands, spiritual-moral duties, for which millions of martyrs (not only Christians!) have chosen to die rather than betray them or hide them in the depths of the soul.

The hidden religion may survive for a while, yet not as a religion, but as a timid and ashamed faith.

Biblical and universal history illustrates the case. In the book of Daniel we find a strong cultural and spiritual conflict between the religion of the young captives brought from Jerusalem and the religion of the Babylonian conquerors.

The revealed, biblical religion is not just a thrill of the heart, it is life itself, lived according to the divine commandments. The Ten Commandments were also called the Covenant—a contract of faith, love, and obedience between God and the believer. These commandments forbid any form of respect and attention to other gods. The contract between God and the people was likened to the covenant of marriage, which is why unlawful attention to other gods is called unfaithfulness or “adultery” in Scripture.

But in Daniel’s world there were no such “prejudices”. The Babylonians had enough gods for all their real and imagined needs. The Jews had been delivered into their hands by God precisely because they had been unfaithful to God. In exile they kept the true faith hidden in their hearts, but in public they were like everyone else. This is also true for the princes who were taken hostage in the imperial palace.

They ate what they were given, worshipped as they were commanded. They had a private religion they no longer believed in, and a public one they dared not renounce; split consciences. Only four of them were exceptions and showed a respectable difference because they dared to express their religion publicly, even at the risk of their lives.

True religion survived by the dignity of public expression. Jesus said: “If anyone is ashamed of me and my words in this adulterous and sinful generation, the Son of Man will be ashamed of them when He comes in His Father’s glory with the holy angels” (Mark 8:38).

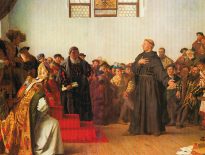

In the early centuries, Christians risked their lives to profess their faith in public. The Middle Ages are full of martyrs of honour, whatever religion they professed, and even today there are people who suffer for not keeping their religion quiet in their hearts.

Among the last words of Scripture we find the heavenly condemnation of the religion of cowardice and infidelity, which, by concealing the truth, by complicity in silence, is associated with the most terrible sins, including idolatry, and is defined as a life of lies, destined for the “fiery lake of burning sulfur. This is the second death” (Revelation 21:8).