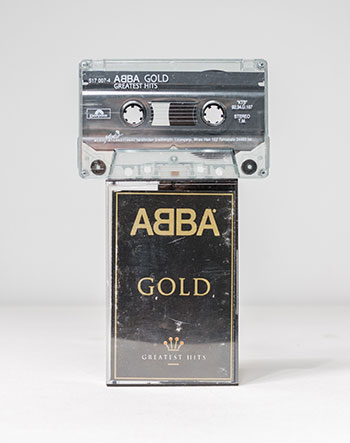

After 40 years, ABBA has made a return to the music scene with an album primed to awaken or indulge the nostalgia of generations who lamented the breakup of the Swedish group in 1982. The album comes with a virtual concert in which the group performs all their new songs, with a twist: with the help of digital technology, the singers will appear as their younger selves.

As for many other children of the 80s, for me, ABBA songs are synonymous with road trips without air conditioning, the windows rolled all the way down, to a destination that promised, every time, to host the most beautiful summer vacation. So I was eager to listen to “I still have faith in you”, the first track from their new album, paying attention to what has changed and what has remained the same in the inflexions that gave rhythm to my childhood. Then I saw the teaser for the concert.

Producer Ludvig Anderssen (Benny’s youngest son, one of the ABBA members) told how “Agnetha, Frida, Benny and Björn got on the stage, in front of 160 cameras and almost as many VFX [visual effects] geniuses, and they performed every song in this show to perfection, over 5 weeks, capturing every mannerism, every emotion, and the soul of their beings, so that becomes the magic of this endeavour. That when you see this show, it is not a version of, a copy of, four people pretending to be ABBA, it’s actually them.”

In the “I still have faith in you” video, there is a sneak peek of this digital concert and, unfortunately, as a mere spectator, I could not help but notice the minimalist emotion of digitized faces, which betrayed the artifice.

The old videos with the four artists in concert or at recordings had prepared me for something else. I was waiting to see them performing as they are today: with white hair, a few wrinkles, a few extra or fewer pounds, but still them. And the reality made me think: Have they assumed that the fans still want them to look young, as if they were immortal? And are they right?

Reunions and epiphanies

Perhaps in the context of the introspection generated by the isolating atmosphere of the pandemic, 2020 and 2021 seem like the years of reunions: the actors of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and Friends reunited after three decades. I saw interviews in which artists who became famous in adolescence reviewed their experiences through the eyes of an adult. It is true that some events were romanticized, but others were presented in a light in which no one but the artists saw them because only they had lived them. The approach was, in itself, something therapeutic.

We identify with the artists and, with them, we look back and realize that we have the privilege of still being here to see how many of our expectations have been achieved, how many of our sacrifices were worth it, how much of what we thought to be real actually was, or still is, real. It’s a reality check that I’m convinced is good for us, because it tells us something about what we’ve been through and who we are today. These reunions of performers once at the height of celebrity have the advantage of looking at the appearances of that time with a certain detachment, and that is why they teach us something about the world, and life.

We look at the stars of that time and notice that their humanity has eventually overshadowed the aura of ‘godlikeness’ they once had. We see how, in fact, they were just people, from the very beginning, even if, intoxicated by their own fame, they wanted to believe what a whole world thought about them: that they were special, that they had something that no one else had, that they deserved to be loved, that they would always be supported by those who were overwhelmed with emotion at their mere appearance, who called their name as an incantation, who showed them a devotion which they themselves had never shown to anyone.

This is good for us because it comforts us in the face of our own perceived failures. We notice how once-adored celebrities are today more grateful for the things we have also experienced, rather than for the unique things only they have experienced. For the friendships in their work teams, for the support from their families, things that are accessible to “ordinary” people as well.

Then we see what they regret: that because of the time dedicated to their careers, they lived more among strangers than at home. They missed important moments in the lives of loved ones because of professional commitments. They exhausted themselves by not wanting to disappoint, or simply out of a desire to accommodate everyone. And we learn from all this that it is very possible that, although we are not stars, we actually live better lives than they do. We don’t have their money or fame, but we have something else that matters more.

Regret as a gift

If ABBA had shown themselves the way they are today, maybe people would have noticed that their synchronized dance moves are not as flexible as in their youth, that maybe they aren’t as full of energy as they were 40 years ago, that maybe the relationships between them, having been through so much over the years, are no longer displayed according to the visual language in the old videos, because in time they learned to act for the camera. These are, of course, nothing more than mere intuitions. But they are also an invitation to think honestly about how much they would affect us if they were real.

It’s normal for us to feel regret when we see the limits inherent in old age. But isn’t it wiser to accept both regrets and limits than to hide our real selves behind the illusions of an eternally young hologram?

Today, we are what we are: with our eyes less wide open and less sparkling than in childhood when we were fascinated by each discovery. Our eyes have seen suffering, weeping bitter tears. It is normal for them not to shine the same way. Today we may open up more reservedly to the people we’ve recently met, but our souls have also experienced disappointment and it is normal to be a little more cautious.

Or maybe, on the contrary, today we are stripped of the shyness that once imprisoned us, in the days when people seemed like threatening icebergs, or impenetrable fortresses. Maybe today we look at the world free from our ignorance or the feeling that we deserve everything, which were the only realities we once knew. Why not cherish these changes instead of wanting to stay in a past that, in reality, is smaller than who we are today—no matter who we are.

Even the fact that we often fail to reconcile with who we have become, or are becoming, is still a precious gift. It is the realization that our soul desires, in its insufficiently-explored depth, something that this life only offers for a limited period. We want to always be young and creative, to always have interesting plans ahead, and to feel that the world is ours, and that nothing holds us in place. Because although we are not good at everything we want to be, we still have time to learn. We still have time to see everything we want to see, to experience emotions we have not yet experienced.

Reality inevitably denies us these aspirations—to some more than to others. Even animals are subject to the same reality. But only people know the painful regret of this refusal. Some resign themselves, defeated in the face of it, others even try—somewhat against nature—to normalize it. Others, like ABBA, hope to forget about it, for at least a moment.

A different proposal

The human desire to live forever, so foreign to evolutionary mechanics, naturally legitimizes itself in the Christian faith. We have been created for eternity, not for a temporary existence, as intelligent and creative beings who aspire to become the most cultured fertilizer of plants. And the limits of our existence hurt in direct proportion to the reality of the purpose for which we were created.

As free beings, we had the right (and we used it) to deviate from our purpose, to try to live according to an agenda different from that of the original plan. But, paradoxically, although in our souls we have become alienated from the One who created us and even from our true selves, forgetting how to be truly happy, the pain of unhappiness and loss remains. It is a constant reminder that we are not on the right track.

That’s why we say that pain is still a gift. If we lost it, we would lose ourselves. But if we recognize it and face reality as we are, we are more likely to end up in a context where we hear the good news that it is possible to live forever, no matter how impossible and insane it sounds. Who taught us to long for this madness?