When we consider that a conclusion is founded only if a lot of people consider it true, we fall into the trap of the argumentum ad populum or the appeal to popularity.

Enhance your critical thinking. Read more of our articles on the topic.

The argument by appeal to popularity can be considered a subspecies of the argument by appeal to authority, in which authority is quantitatively justified. The voice of the majority becomes for us an authority. In other words, we accept an unverified or unproven conclusion just because it happens to be supported by a large group of people. Sometimes we give credit to the majority because we tend to believe, like the song says, that ”50 million people wouldn’t be wrong”. But what if they are?

Why it’s tempting to go with the herd

Sometimes we tend to believe ideas that are held by many people because we suspect that someone once demonstrated those things, otherwise not “everyone” would have believed them. “Everyone” is a vague concept, however, which many of us have probably already used in trying to convince others. (“Everyone wears flared jeans, Mom! Stop buying me straight ones.”)

At other times, people may rely on the opinion of the majority because they do not understand the truth as an absolute, which can at least be argued logically, if not proven to its last fiber. (“No one came back to tell us if there is life after death, so for now we’ll believe what all our ancestors believed.”)

Some are guided by the majority because they believe that truth is a subjective notion or that it can be established by convention. (“I don’t know how they taught you in your country, but that’s the way things are done here.”)

If most students who take an exam chose to cheat, those who deliberately choose not to are seen as “suckers.” Although it is clear that those who cheat have a specific advantage over others, the mere fact that they are numerous does not make cheating justified/correct. Likewise, if most politicians steal, it does not mean that theft is inevitable, as in the classic: “They all steal, but at least he also did something for the country, so I will vote for him.”

The exponential power of a herd of authorities

The truth must be true, even if no one believes it. And a lie will remain a lie even if everyone believes it. For more than 40 years, between 1912 and 1953, the scientific community allowed the public display of the Eoanthropus dawsoni fossil, which it believed was the missing “link” to prove the evolution of the ape man. Amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson claimed to have discovered the remains of a humanoid skull near Piltdown in East Sussex. In February 1912, Dawson contacted Arthur Woodwar, curator of the Geology Department at the Museum of Natural History in London, and together they popularized the idea that the fossil was 500,000 years old, announcing it at a Geological Society meeting. In 1953, it was revealed that the two had joined the jaw and a few teeth of an orangutan and the hypocephalic skull of a modern-day man, presenting the result as a revolutionary scientific discovery. This forgery popularized with scientific authority was reconfirmed as a scam by a huge scientific study conducted in 2016.

The majority is never a proof to believe nor to disbelieve something

But the reverse appeal to popularity is more subtle. Not that one thing is true because the majority supports it, but because the majority supports it, that thing is false. We find this form of appeal to popularity in the promotion of luxury products (“You don’t have to wash with product X. Product X is for the tasteless and poor masses. You have to wash with product Y.” This argument says nothing about the properties of any of the products. Just say that product X is popular.)

Conspiracy theorists often resort to this form of reverse popularity argument when treating their lack of popularity as proof of authenticity. (“Few know that nuclear weapons are made in the Vatican’s basement.” In other words, “only the elect know the truth. If you do not have this information or believe the opposite, it means you are not among the elect.”)

But if you were to go after the majority…

The argument that “the majority believes so” can only be invoked at most as a call for a convention. In a democracy, the decision belongs to the majority. “We’ve established that we do things a certain way, that’s how we do them.”

But in argumentation, it is good that the decision be based on reflection, on weighing the facts, on past experience, on estimating the consequences. Here’s why.

First of all, in the case of topics that massively polarize opinions, we will not be able to know which majority to believe. A survey conducted in 2017 by the American Association of Cardiologists found that while nearly three-quarters of Americans believe coconut oil is healthy, two-thirds of nutritionists believe the exact opposite. It is obvious that if we look strictly at the majorities, we are left in a dilemma. In the case of the popular majority, the authors of the study attributed the difference in perception to the marketing that coconut oil benefited from in the non-specialized press.

Many who argue in favor of consuming coconut oil say that it abounds in medium-chain triglycerides. In reality, however, this type of triglyceride constitutes only 4% of the total triglycerides in coconut oil.

Secondly, even if they were right, the majority should not have too important a word to say in this endeavor. Because, once invoked as an argument, popularity will take advantage of our innate need to belong to a group and will sabotage us more easily to accept unfounded majorities. (“So what if you’re right? That’s how we’re used to doing things. We don’t change.”)

Most likely, we will not be able to protect ourselves at all from the attraction of the majority appeal. And, as the philosopher Chaïm Perelman put it, with regard to rhetorical arguments, “it is useless to try to define the rational argument (…) after its conformity to certain prescribed rules. (…) Arguments are never right or wrong; they are either strong or weak, relevant or irrelevant.”

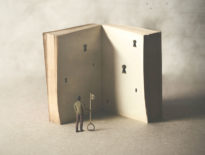

But it takes an independent mindset in order to judge, based on our own reasoning and taking responsibility for our own conclusions, which argument is the most convincing.

Enhance your critical thinking. Read more of our articles on the topic.

Alina Kartman is a senior editor at ST Network and Semnele timpului.