“Am I still human if I’m afraid?”[1] The question asked by a well-known fictional character can be the starting point for reflecting on how we learn to live with our fears.

A history professor and resident of a provincial town, the main character in the novel Life on a Platform, ends up being terrorised by cobra charmers. At first, the locals treat the charmers with a mix of pity and disgust. Some toss them a coin, avoiding eye contact with the cobras, while the charmers keep their eyes lowered, as if ashamed of their livelihood. As time goes by, however, they grow bolder. They take their cobras out of their baskets, place them on the sidewalk, and begin playing flutes, threatening passersby who don’t contribute to the prominently-displayed hats. Feeling unsafe on the streets, people barricade themselves in their homes, but the charmers follow them there, ringing insistently until the door is opened.

Sick and tired of the charmers’ harassment, the professor flees the town, and a phantom train carries him to a station that seems to be located at the end of the world and time: the station’s only functioning clock shows only the minutes, and the boards dutifully display arrival and departure times but not the trains’ destinations. No train appears on the horizon, and the professor realises in his wanderings that the tracks turn into sand beyond the forest’s edge, where the desert begins. Even here, the charmers sniff out the fugitive’s trail, and the professor realises that the ending of his story depends on the choice he will have to make: either to allow himself to be bitten by the cobra or to attempt to tame it.

If we extract the story from the tangle of meanings and symbols in which the author has clothed it, and focus only on the thread of confronting fear, the professor’s experience begins to lose its strangeness. The way fears emerge from the darkness and twist their bodies in the citadel of our minds is familiar to many of us, even though their intensity (ranging from unease and nagging worries to sheer terror and anguish) varies from one individual to another. Specialists say that fear, anxiety[2], and shame are the key emotions behind almost any problem we struggle with, and, at the same time, the fuel of our unhappiness[3]. However, the problem does not lie so much in the presence of these uninvited companions, but in the unproductive, unhealthy way we receive their messages and react to them.

Viewing reality through the cyclopean eye of fear

A realistic X-ray of fear will show us that the scenarios it embroiders are either manageable problems—not the imminent catastrophes envisioned by our minds—or (most often) scenarios that will never materialise in reality.

We learn from an early age to handle fear as a shield to protect us from threats, convinced that, in its absence, we would not be prepared for the dangers lurking around us, psychologist Todd Pressman says. In reality, fear generates or amplifies suffering rather than diminishes it, but as long as we do not realise how distorted the messages it sends us are, we continue to believe what it tells us. There are several mechanisms through which fear distorts our perceptions, the psychologist says. The hypnotic effect of fear is one of the most well-known: it builds a wall between us and reality, projecting countless versions of disaster upon it. Getting stuck in a loop where we obsessively review every possible threat is another mechanism through which fear sustains and reinforces itself.

The pressure to find present solutions for future (and, moreover, hypothetical) situations adds even more power to negative emotions.

We might realise that this endeavour is futile since we don’t know if a threatening scenario will materialise, but fear demands that we take action anyway. Therefore, we anticipate future experiences (especially anxieties) as if they have already materialised. And because we don’t have tangible things to solve, the feeling of lack of control exacerbates fear. Ultimately, fear perpetuates itself because our attempts to control frightening circumstances that do not yet exist roll the anxiety snowball, making it even harder to destroy.

Deconstructing fearful predictions

Some of the things we fear do sometimes happen, but usually in a simpler form than the scenarios produced by fear, and not even as frequently as we are tempted to believe they will occur. However, when fear takes control of us, it consistently delivers two messages: that truly terrible things will happen, and that we won’t be able to handle them. Cognitive-behavioural therapy experts call the first type of message “likelihood estimates” (the chances that the fear will come true) and the latter “severity estimates” (how bad things will go if the scenario materialises).

We know from experience that fear irrationally and unjustifiably increases the probability of bad things happening to us. The statement attributed to the French philosopher Michel de Montaigne captures the essence of anxious thinking: “My life has been full of terrible misfortunes most of which never happened.”

We overstate the probability of our worries materialising—this was the conclusion of a recent study conducted on a small sample of people diagnosed with generalised anxiety disorder. Subjects were tasked with recording their worries over a period of 10 days, also noting their severity. Four times a day, volunteers received messages asking them to record the worries they had experienced in the previous two hours and that could materialise in the next 30 days. The results showed that 91.4% of the worries the subjects had did not happen. In situations where fears were confirmed (8.6%), the outcome was better than expected in about a third of cases. The non-confirmation of false expectations led to a reduction in anxiety symptoms (the most common percentage of false worries per person was 100%!).

Unfortunately, there is no evidence that we are more accurate in estimating the severity of a future crisis than we are in estimating the likelihood of it occurring. What are the chances of us truly being overwhelmed in the 8.6% of cases where we will experience the events we feared would happen? Even if things do go really wrong, it won’t be as dire as fear suggests, says Gillihan, explaining that fear makes us unable to see beyond a crisis, as if that were the end of our story. In reality, history shows that we have been able to cope, one way or another, with the discomforts or crises that have come our way. None of them have been insurmountable (except death, beyond which there are no fears anyway), the psychologist says.

From avoiding fear to taming it

There is already an abundance of books and programs (with and without medication) that help people control specific fears that prevent them from carrying out everyday activities.

Even though expert opinions on fear may sometimes differ, there is a consensus that the best strategy to control fear is to befriend it. Practically, this approach involves[4] learning that fear will appear (or reappear), identifying it when it hides behind other emotions, deciphering its mechanisms, tracking how it intensifies and fades, and understanding how we automatically react in its presence, psychologist Harriet Lerner says.

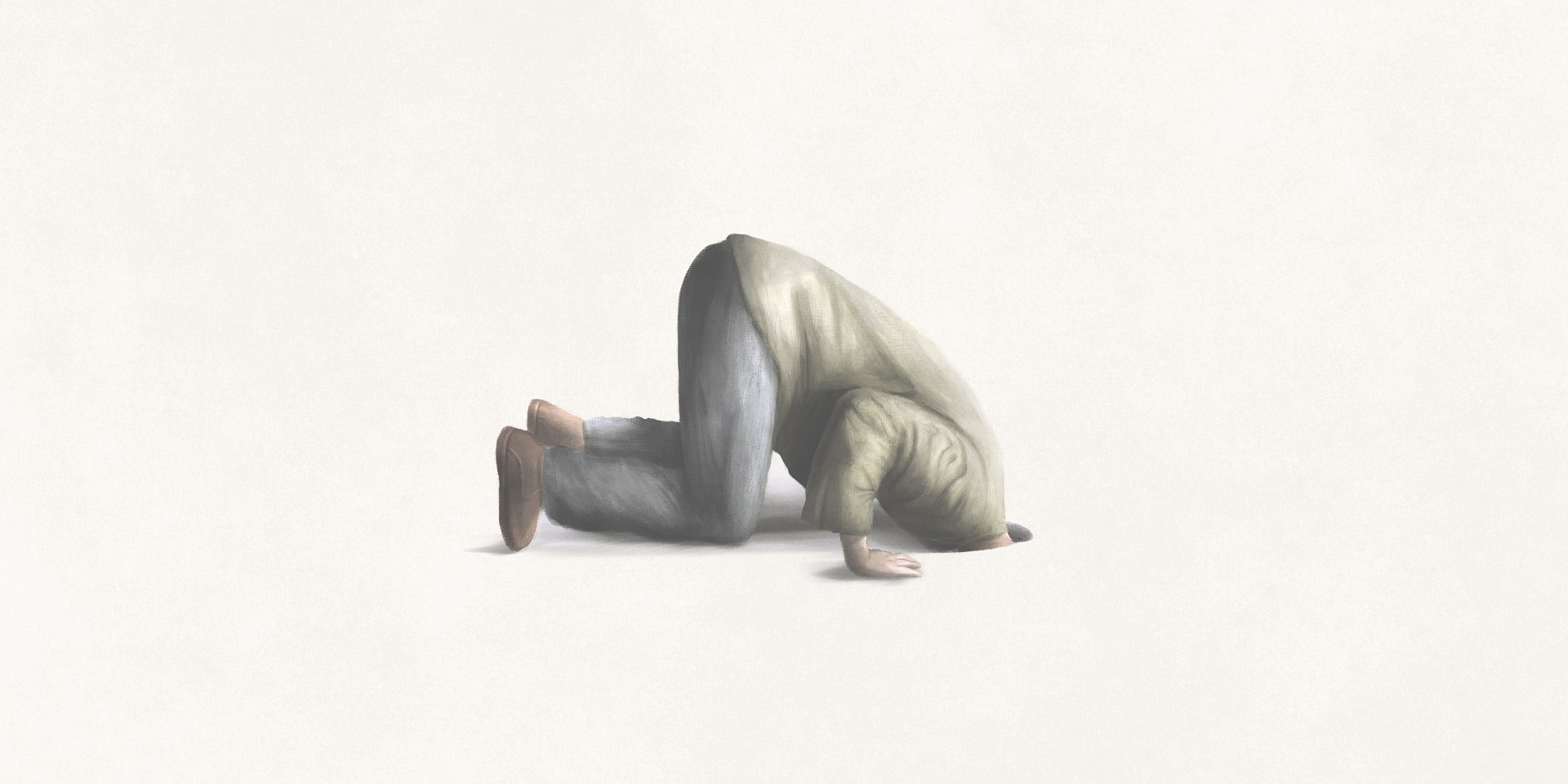

If befriending fear is the most reliable approach, the “fear of fear” is the primary reason why we fail to manage it (or heal from it in clinical cases), Pressman says.

“Fear’s trickery depends upon its ability to convince us not to look at it deeply,” says the psychologist, noting that we typically respond to fear with avoidance behaviours, thereby reinforcing its power.

The solution lies in reversing avoidance responses and engaging in actions we’ve learned to avoid due to fear (public speaking, flying, etc.), thus surpassing our need for safety and predictability. Change, however, triggers fear, so having the courage to confront our fears means, in the initial stages, choosing to “become more anxious,”[5] endangering our current status quo.

Exercise was the only way she found to tame a chronic fear, says psychologist Harriet Lerner, describing her fear of flying after having children. For years, she adopted the strategy of flying separately from her husband to protect her children from the risk of becoming orphans. This decision made no sense, says Lerner, recounting that from the airport to the hotel, the spouses took the same taxi, even though her experience showed that the possibility of a terrestrial accident in a poorly equipped taxi was not negligible at all. Diluting the fear of a plane crash happened slowly, with each purchased plane ticket, because giving up flying would have had unacceptable professional costs.

Reflecting on her confrontations with fear over time, Lerner noticed that this strategy had been taught to her in childhood, at an amusement park in Brooklyn. Both terrified and tempted by a roller coaster that she had been circling for several summers, she asked a little boy who had just finished his ride how he managed to conquer his fear. The reply came quickly: “You don’t get over it. You just buy a ticket.”[6]

Carmen Lăiu explores the mechanisms that create, sustain, and strengthen fear, examining how the messages conveyed by fear distort our perception of reality.