The issue of education generates heated discussions and numerous controversies. The dialogue with Professor Steve Dickman, the director of a private high school in Savannah, Tennessee, presents a time-proven education model. The objective is not only in the acquisition of knowledge, but also in the skills to apply it in real life, for one’s own good and the blessing of others. The by-product of such an education is nothing more and nothing less than happiness.

Your connection to Harbert Hills High actually begins before you were born.

Indeed. My parents studied at the institution that served as a model for many other schools, Madison College. One day, one of the employees, William Patterson, said to those gathered in the chapel: “I’m planning to start a school and I need some people who will help me. Who is here today that would like to come and be a part of this project?”

Mom elbowed dad and said, “Louie, I think that’s us.” They volunteered to come and help start the school. So, in 1955, after my father finished his master’s degree at Peabody, he and mom came to Harbert Hills Academy. The first students arrived in 1956.

So, your parents were the first to teach there and manage the property?

They were more or less the driving force that maintained the institution over the years. That’s where I was born in 1957. I was raised on the campus of Harbert Hills Academy.

This means that, since then, you have always had a connection with this institution. You grew up, studied, and worked there. Was it that simple?

It was not exactly that simple. But I attended elementary school there and then high school.

Share with us some of your memories from those times, something about that pioneering atmosphere.

Knowing nothing different and being raised in that environment, I thought that everyone was raised the same way, that everyone lived in the countryside. It was very nice surroundings for a boy.

I enjoyed being there, because my mother would allow us freedom to go and run around in the woods, because there was nothing to hurt us. So, we would go exploring in the woods and we would have a great time.

It is true that my parents were busy, but many times we participated in the work as well. We were not isolated at home. Home was work and work was home. It was all together. The students would eat sometimes at our house, because the high school did not have a cafeteria. I was raised in a large family atmosphere.

I remember a couple of things early on. The first building was being built, where there would be classrooms and a cafeteria. I was about four years old. It was a Friday afternoon, the crew was working very diligently to complete the last little bit of the roof so that if it rained, it wouldn’t get wet inside over the weekend.

Mother took us home, bathed us for the Sabbath, she put on our very best Sabbath clothes, and said: “Boys, don’t go to see the project, because you will get dirty!”

That sounded more like an invitation!

We right away decided that we had to go and see what was happening. As we arrived on the project, they were in the midst of busily putting the last tar and gravel on the roof. We couldn’t resist climbing the ladder to see what they were doing. By the time we got down, we were well tarred! The walk home was not as pleasant as the walk up, because mother had found us in that situation, nicely tarred for Sabbath.

I won’t ask you what happened after that…

I think we received a kerosene bath and that’s how we got rid of the tar! In a supporting ministry institution, industry is a part of what’s required to make it work, because there is no outside source of income. My father, Louie Dickman, and Mr. Patterson’s son, David, were in business together in Nashville as they completed their work at Madison. He and Mr. Patterson had started a furniture making business before they graduated from college and eventually began to work on pianos.

Mr. Patterson was a talented musician, my father was handy, he could make furniture, and they started rebuilding pianos. They made them look like new. It was an amazing little industry. Harbert Hills needed an industry, so they moved the company headquarters to the Harbert Hills Academy campus and, to survive, they had to rebuild 12 pianos a month.

Twelve a month?!

They would bring in 12 pianos, the students would work there and learn the necessary skills, and the adults would supervise them. Students worked half a day and went to school the other half. That was the industry that helped maintain the Harbert Hills Academy.

How old were the students?

Between 14 and 18 years. There were young men and ladies learning what it meant to be productive as well as learning.

Refurbishing pianos is something that requires a lot of craftsmanship—it’s not just about cabinet making; it’s probably the high end of this craft.

In 1958, they added another industry to the school. My mother and Mrs. Patterson were both registered nurses, trained in Madison. Prof. E.A. Sutherland, the founder of Madison College, said that if you want a stable institution, you need to have an agricultural, a medical, and an educational branch work together. The people at Harbert Hills recognized that they had done nothing in the medical field, so the people there decided to start by taking care of the elderly in what’s called a nursing home.

They applied to the state to receive approval from the authorities and were asked how many residents this home would have. They thought of three because they had a little house that they were going to use to start this nursing home.

That is another story in itself, as Mr. Patterson had previously worked for the federal government. One of his jobs was to enforce the laws. His job involved prosecuting people, bringing evidence against them and actually putting them in prison if they’ve done wrong. One of those people he had put in prison had told him: “Mr. Patterson, if I ever get out, I’m going to come see you!” It wasn’t something he thought about all the time, but he was always a little bit on alert.

One day he was sitting in his office at Madison. They were starting school, so he went back and forth. That man came in, sat down and asked him:

“Mr. Patterson, do you remember me?!”

“No, I don’t believe I do.”

“My name is Roger Hayes.”

“Nice to meet you, Mr. Hayes.”

“We have met before.”

“Under what conditions?”

“You put me in jail and I said that if ever got out I was going to come back and find you, so here I am. Don’t worry. I heard about what you’re doing down in Savannah, Tennessee, and I want to help you. I want to build a building for you on your campus.”

“We are trying to start a little nursing home.”

“How much is it going to cost? I would like to build it myself.”

Thus, one of the people that Mr. Patterson had put in jail, came and donated the money to build this little building for the nursing home. If somebody funded a building it was Mr. Patterson’s practice to name it after him. He looked at Mr. Hayes and said: “I’m sorry, but I can’t name this building after you because you’re a gangster. What would that look like? We’re a Christian school.”

Was Mr. Hayes still involved in illegal activity?

I don’t think he was totally in it, but Mr. Patterson was not comfortable naming the building after him for some reason. Mr. Hayes said, “No problem, you can name it after my mother.” So, the little nursing home was called the Clare Ellis Hayes Home. We began receiving people from the community that needed care and we took care of them. The boys were working in the piano shop, and the nursing home was the place where the girls were trained. Gradually, the activity expanded. Now the home has 49 beds and is our main industry.

How is the piano repair workshop going?

The piano shop eventually faded away, because it is now cheaper to buy a new piano than to rebuild an old one. Japanese manufacturing came into the market and it was difficult to keep pace with that.

This shows some of the challenges of this field. Let’s expand a little bit on this concept of a school educating young students comprehensively—not just focusing on mental knowledge or even learning a craft, but educating young persons to be deep thinkers, to be knowledgeable of the Word of God, of science and, also, to be able to do something with their own hands or to run a business. This is something which is lost nowadays.

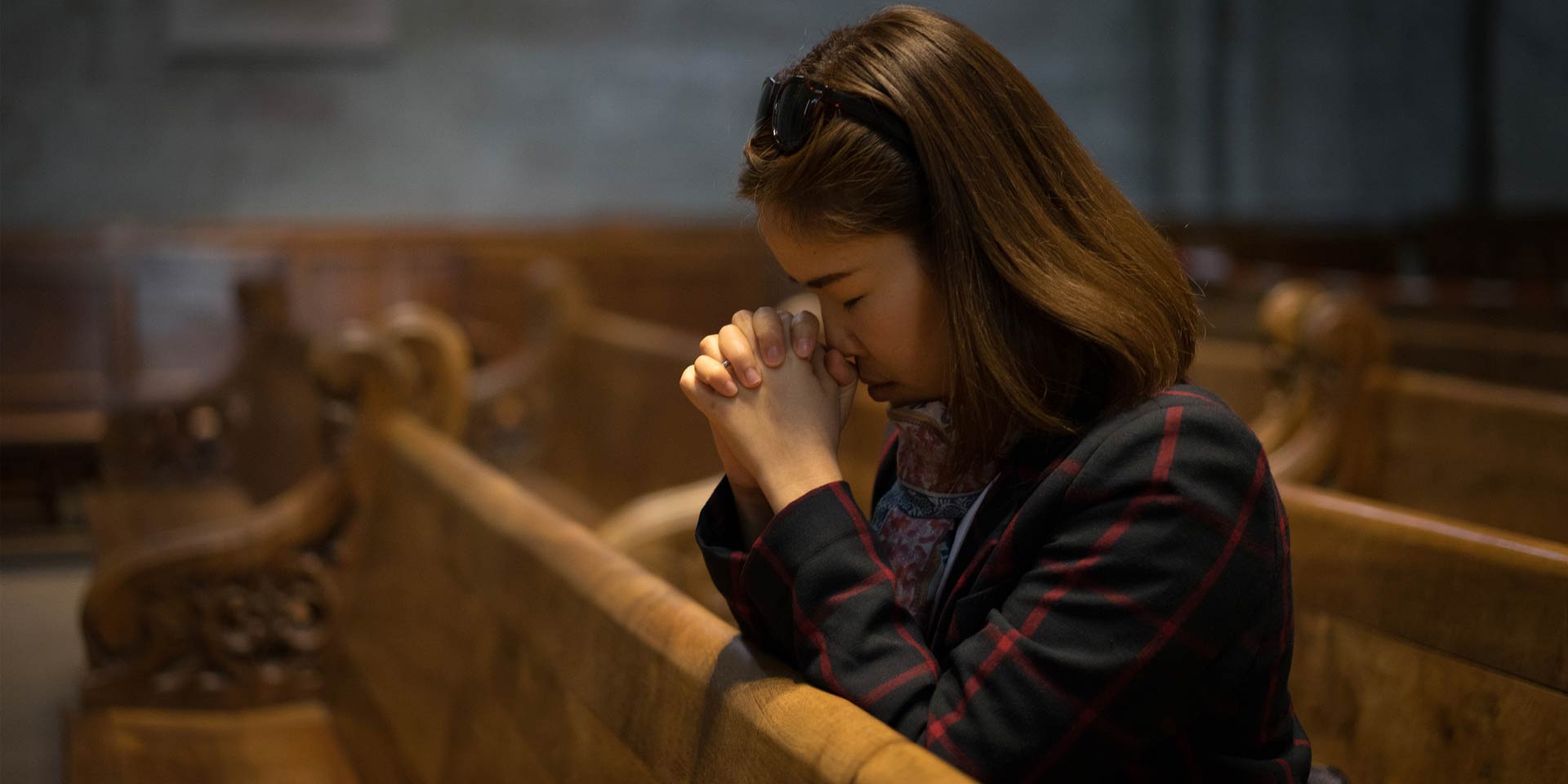

One of my favourite verses in the Bible is in the very beginning when, before sin entered our world, God outlines for us His entire plan for education in one sentence. This is God’s way of organising things. It’s simple, but you’ll never fully comprehend it. The passage I am referring to shows that God put Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden “to dress it and to keep it.”

This is the key to education. The real purpose of education is to gain a knowledge of God. Man was created perfectly, but he wasn’t created with all knowledge, so God put him in a place where he could advance and learn more and more about who God is. The place He chose was not a classroom with a computer, but in the midst of the things He had created.

He gave man useful work to do, as a component of education. God was the teacher, the schoolroom was nature, and the useful work that He gave to do was a part of that education. The fourth component of God’s plan of education is just the experiences of life.

We have come to believe that education takes place mostly in the classroom and is mostly about the mind. But if you study the Bible, from cover to cover, this is the model of education that I have personally found to emerge. After the appearance of sin, God arranged for people to live on small farms and educate their children there, their parents instructing them and having very frequent contact with nature, doing useful work and, of course, dealing with the regular experiences of life.

Later, God instituted the schools of the prophets, where we find the same model. The prophets established those schools. They built them themselves, prepared their food, and studied the Word of God.

Nowadays, students reach high school and know very little, if anything, about practical work, nature, and many things. They are very good at using their smartphone, their computer…and that’s a good skill to have, but it is not the most important.

It cannot replace real life.

I grew up in this environment and I think I have an appreciation for the things of nature and practicalities of life. These are the things that speak about our Creator and that were made for a purpose. God wants to teach us as we associate with nature.

What kind of lessons can we learn this way?

Early on I asked my father: “Dad, I would like to have a bicycle.” He said to me: “Son, that’s a good idea, but I don’t have the money to buy you a bicycle. You’re going to have to learn to earn your money for a bicycle.” I said: “Okay, Dad.” He said to me: “Here’s a little piece of land. You can grow some vegetables and sell them. If you can sell enough vegetables, you can get your bicycle.” My brother and I started cultivating that piece of land.

Do you remember how old you were?

I was about nine or ten years old.

That was harsh!

I think so. But it taught me something—if you plant something and don’t take care of it, you won’t harvest a crop. It taught me that you reap what you sow.

These are lessons for life, not for farming.

The field was about a mile and a half from home and we would walk there. Dad would help us plant the vegetables, and then we would take the hose, water the field, collect the harvest, and he would help us take it to town and sell it. His plan was to teach us to be workers and to know what to do in various situations.

When you let weeds grow in your garden, they’re hard to get out. If you get them out when they’re young, it’s a good deal. But when you let them grow big, they’re really hard to get out. I’ve learned that, in my own life, if I let bad habits take over, they’re hard to get out later on.

Do you think that at that age you were able to make such connections?

No, I just looked at it as hard work. I don’t think I was making all the connections at that point, but as I think back on it, I see what I was learning.

My father worked with young people all his life. He found young people many times desiring to be happy but did not really know how to get there. He had this saying: “True happiness is the by-product of unselfish service for other people. You are not going to find happiness by going out looking for it. You’re not going to find happiness by intentionally going on a journey to find it. But if you serve other people unselfishly you will find happiness.”

I tried to include that and engage my children early on. The school does a lot of mission work, we do a lot of mission trips because we want them to learn that the world is bigger than they think, than the local town, than the mall or wherever they may live.

We offer them the opportunity to get involved in community service. We engage them in building things on mission trips, cleaning up after tornadoes and hurricanes. All of these are experiences that will help students understand that they have to get outside of themselves to find true happiness. They come back smiling. Plus, they like being out of the classroom anyway. Who likes to be in the classroom?

It gives them that balance. They’re able to get outside the classroom and engage in real things, doing real things for real people. Then they come back into the classroom. The idea is to give them a balanced education—and for them to learn by experience that happiness is within their hands.

Thank you very much for sharing with us important moments from the long history of this outstanding school and the way the lives of many generations of students were prepared for both this world and the one to come.

Note: This is a TV interview by Adrian Bocaneanu, broadcast on HopeTV channel Romania. The transcript of the interview has been edited for brevity and clarity. You can watch the full version here.