“Love means never having to say you’re sorry.” When I first heard this line from the “Love Story” blockbuster, I thought I was the only one who didn’t understand what it meant. However, after watching a recent interview with the lead actress, I was reassured. She too thought it was a stupid thing to say. Still, the phrase was a hit at the time, because it resonated with an ideal of the era: absolute freedom in love.

When you love, you are free, even in the midst of your mistakes, because the one who loves you knows that you reciprocate their love and that the mistake is just that: an error, not an attack on the love you share. So, then, what is there to be forgiven for?

Besides the fact that, in real life, people can love you to the moon and back today and then become as cold as the cosmos tomorrow, they can also hurt you deeply, even if you’re the one they love the most. Love does not guarantee infallibility, but it is the glue that holds us together despite our mistakes.

The Sexual Revolution Generation dreamed of liberation through love. This article is not a tool to chastise that dream and its adherents. It had its premises and has already paid its price. Today’s generation, however, although it does not have the same premises, lives in the steam of that revolution and tends to adopt similar philosophies without knowing where they came from and what their price is. Did the members of the Flower Power generation need to know better? Could they? We are already treading on the dangerous ground of judgement and it’s not a good idea to go there. There is one thing that is more useful: realizing that the relationship between love and freedom is a very complicated one.

We are never more captive than when we love

Love is not meant to feed our freedom—it does not exist for that. On the contrary, love binds us. When we are born, our mother’s love teaches us that it is beneficial for us to be dependent on her. And it’s good that it teaches us this: how many dangers would a baby “in search of freedom” be exposed to, separated from the person who takes care of them?

As we grow up, it is love that teaches us obedience and discipline. If we could learn them in a different way, we would grow up as trained animals, not as whole people. In our teens, love crystallizes our identity, which, under the centripetal force of the hormonal storm of emotions, would break into thousands of pieces if something called “love” did not bind us to some fixed landmarks: principles, people, God. Then, love ties us to a he or she and forbids us to give our hand and our soul to another. Love welds our desires to the desires of the other. Then we have children, and our love for them makes us even more captive: because of tens and hundreds of reasons, we no longer count, but they count immeasurably. Our freedom is secondary. Our parents get old. And the love that binds us to them also binds us to their pains, to their inabilities, to our demise that comes with their demise. Then, we are left “alone”.

Friends change, children leave home, parents die, and when the bonds begin to unravel, we realize that we don’t even like freedom! Freshly wiser, we end up with the gift of our own old age. And we bond again. Instead of the freedom to live our final days as they come, we accept our lack of it and let ourselves be helped by those who love us and who, through their help, give us something, while taking other things in return (our privacy, self-confidence, and dignity). We connect with people who ask us how we are, about memories, TV series, pets, the child of the young neighbours, and recollect how beautiful it was when we guarded the sleep of our little one, who is big now and doesn’t call anymore.

Love does not set us free by any means. Sometimes it makes us even more of a prisoner than we would like to be. And sometimes, or maybe even multiple times, that bond of love that makes us feel good, like a hug, becomes too tight. It hurts us. It strangles us. Like when we love ourselves too much and lean inward, and we can’t see anything around us from this position. We suffocate from the weight of our own heads. Or when the one we are bound to suffers and everything in our being that is attached to them suffers too; when those we love depend on us too much, and their dependence is heavy and we can no longer step forward. Or when we ourselves depend too much on those we love and feel like children in adult bodies, trembling at every dissatisfaction of our loved one, as we did when we didn’t want to lose parental approval. Then we lose our freedom. This loss, however, is not a loss at all. Rather, it is getting lost.

We no longer know where we put our freedom, what we did with it, and how to regain it

How do we get it back? By looking for it where we were taught it is to be found. If we have had the privilege of a Christian education, we will be familiar with the statement “the truth will set you free” (John 8:32). If we have not had the privilege of such an education, we may be acquainted with the situation it describes even if we are not acquainted with the actual statement. What can restore our freedom, when love makes us more captive than we would like to be, is the knowledge of the truth—to have intellectual preoccupations: that is, to be curious to find out how the world around us works, to keep our amazement in the face of nature and the countless wonders that surround us and are too often ignored, reduced to the invisible, even though they are right there under our noses.

Knowledge (whether philosophical, scientific, theological or any other kind) would no longer seem a snobbish approach if we made it our own, if we let our hearts vibrate every time the mind understands something it did not understand before. Without a trace of cynicism, we would approach that state of exploration that we had when we were children and everything was new and, because it was new, every discovery was the culmination of an adventure.

If we allowed the truth to set us free, we would enter that rich circle in which the great thinkers of the world reside; those who have had the generosity to leave us the fruits of their own struggles and their own intellectual tortures; those who have had the same dilemmas as us, but whom time, inspiration, wisdom or all three have helped to reach one step, two, nine, higher than us in their understanding. If it is true that “there is nothing new under the sun,” why should we cover our ears and not listen to the voices of those who have seen the sun shine long before us?

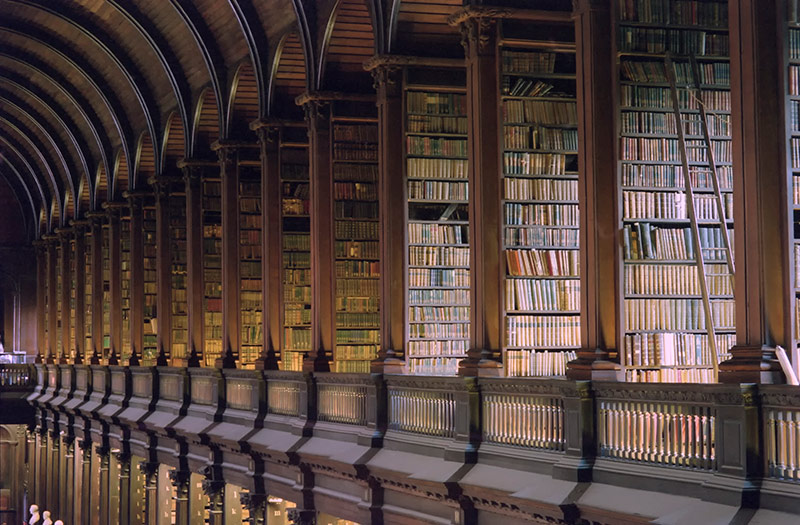

We so often hear people express the regret that “we lack mentors”, and that “young people no longer have role models”. If you don’t have mentors, ‘buy’ them from a bookstore (or get a library permit). There isn’t enough time to make friends with all the possible role models that could fill our lives. The good news is that you end up finding at least one. To live that incomparable experience of hearing the echo of your feelings or thoughts in the writings of someone who did not stop where you got stuck, but went on. Once you find a thinking partner, the world will no longer seem like a mixture of paradigms that do not communicate with each other, but a breeze of overlapping veils that cover and reveal mysteries.

Looking for people who have seen the light

When love binds us too tightly, with a rope that hurts us, we need to look for people who have lived what we live, who have suffered what we are suffering, and who have seen the light. However, more than knowing that such people exist, we need to know their story, their becoming, because that’s how we learn how we can make it. This is the difference between an idol and a mentor: you love and admire the idol, but the idol leaves you where you are, because they need you to remain their inferior. The mentor lifts you up because they’re moving forward. In the fight to keep up with them, you move forward as well. But this is already too abstract. Most of the time, when it hurts, complex things don’t comfort us, but the simple things do. A hug and an “It will be okay, you will see”, said with conviction, is often all we need.

Therefore, beyond friendship with the great craftsmen of truth, what will truly help us is a deep friendship with the Truth itself. Here, the abstract dissipates, because, from a Christian perspective, the Truth is not in fact a concept, but a Person. “I am the way and the truth and the life” Jesus Christ told His disciples when they were most confused, during the Last Supper. That evening, Christ was trying to prepare His disciples for the hardest exam of the class He had taught them, that is, His death. He knew that the disciples would be traumatized by the frightening sequence of events that followed—His humiliation, torture, and murder—and He tried to comfort them, at a moment when the only thing that tortured them was the unknown.

“Do not let your heart be troubled,” he told them. “You believe in God; believe also in me!… And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come back and take you to be with me… If that were not so, would I have told you?” Simple words, as if for children, but powerful in the life of some adults, not because they are infantilized, but because these words are only abbreviations of the guarantees which the disciples had already received. These guarantees were rooted in all that they had lived through with Christ up to that moment. Similarly, when we seem to be drowning in suffering, our friendship with the One who is the Truth lifts us and those we have connected with, through love. This way you can tell that the love that binds us is not an enemy of the Truth that liberates us. They work best together.

Alina Kartman is a senior editor at Signs of the Times and ST Network.