Even though we have been in a much better place for 700 years now, we know that the passing of time has not eliminated the instinct of persecution from human nature.

Three people, who lived over the course of two centuries, at the fusion of the longest night in human history with the excruciatingly quiet dawn of a morning anticipated like a breath of air by the one lost in the depths. Three men, who lit hope more strongly than the flames that burned two of them.

“No man of the Middle Ages, if we except Marsiglius of Padua, was so independent in his thought or quite so fearless in his utterances as John Wyclif [who died in 1384], and no churchman in the history of Christendom, not even Luther, has been more merciless in his attacks upon the existing church order or more uncompromising in his assaults upon the failings of popes.”[1] “Almost all the distinctive doctrines elaborated by the mediaeval theology were either questioned or flatly denied by Wyclif.”[2]

John Wycliffe, the Englishman, was the first to raise his voice during the fourteenth century, yet his voice had nothing of the timidity of a person who speaks first. He was first in the power of his arguments, and also in the determination and clarity in claiming the freedom of every soul.

***

“As important as the influence of Paul upon the mind of Luther and more important than the influence of Calvin upon John Knox, was the influence of Wyclif upon the opinions and the career of Huss.”[3] “It is doubtful, if we except the sufferings and death of Jesus Christ, whether the forward movement of religious enlightenment and human freedom have been advanced as much by the sufferings and death of any single man as by the death of Huss.”[4] (1369-1415)

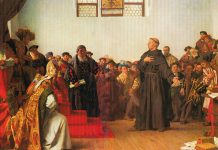

Luther was influenced by Huss’s his last words, which prophesied that although a goose (“hus” in Czech means “goose”) would be burned, a swan would later come, and it would be unstoppable. Martin Luther believed that he must be the swan announced by Huss.

***

Probably not many readers of the King James’s English translation of the Bible know that William Tyndale (1496-1536) is the master translator who shaped most of the expressions used in this version, loved by the English-speaking believers of the past 500 years. It was Tyndale who, before being strangled and burned at the stake, prayed aloud, “Lord! Open the King of England’s eyes!”

Five years after Tyndale’s death, King Henry VIII allowed the Bible, mostly translated by Tyndale, to reach the British people. Tyndale’s dream that people would have the freedom to read God’s Word was fulfilled. This would be the first step along a long road to freedom of conscience in England and then in America, culminating in the Bill of Rights—the name given to the first ten amendments to the US Constitution. In a memorable way, the third amendment forbade the state from interfering with religion, or freedom of conscience.

***

It is with these first glimmers of hope, which promised that one day the darkness of ignorance and terror imposed in the name of God would come to an end, that the long road of liberation from the burdens that have troubled the conscience began. As history has shown, the road has often been daunting and unexpectedly long. And, although we have been in a much better place for 700 years now, we know that the passing of time has not eliminated the instinct of persecution from human nature—and that it will never be able to.

It is up to us to continue to do everything we can—by remembering history and its lessons, by moral education, exercising integrity, and upholding individual rights and freedoms—to prevent the old nightmares of history from catching us off guard.

Because the Bible prophetically speaks of a time in the future when people will be persecuted again because of their faith (Revelation 13:16-17), we have to strive not to end up on the wrong side of the fence, but on the side of those who are convinced that the Sovereign of the universe will put an end to the history of sin and will forever erase the source of one of our most inhuman instincts: the instinct of persecution.

Norel Iacob is the Editor-in-Chief of Signs of the Times Romania and ST Network.