The term “Anglicanism” denotes the system of doctrine and practice of those Christians who are in communion with the archbishop of Canterbury. The beginnings of the Church of England are linked to the reign of Henry VIII and Edward VI, while the initial formulation of Anglican principles is linked to the reign of Elizabeth I, during whose reign a middle ground was politically established (“via media”, in Latin) between the Roman papacy and the Reformed dissents of Geneva, and Anglicanism as a doctrinal system took shape.

The word “Anglicanism”, which probably comes from the French “gallicanisme”, began to be used in the 19th century and is a term derived from the older “Anglican”.

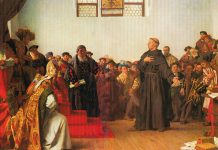

During the reign of King Henry VIII, more precisely in 1534, the Church of England dissociated itself from the Roman Catholic Church. Once the path was cleared, Protestantism advanced rapidly under Edward VI (1547-1553).

However, Queen Mary (1553-1558) succeeded to the throne, and under her reign England was converted to Roman Catholicism. Against this background, a significant number of Protestants were forced into exile. Many of them went to Geneva, where John Calvin’s church seemed the perfect working model of a disciplined church.

Also from the experience of exile came the two most popular books of Elizabethan England—the Geneva Bible and the Book of Martyrs by John Foxe. The two works represent the motivation of English Protestants to see insular England as a nation chosen by God to complete the work of the Reformation.

Thus, Elizabeth’s adherence to Protestantism in 1558 was warmly welcomed by Protestants. However, while the Queen’s early actions were welcomed, on the one hand, because they restored Protestantism, on the other hand, they were also disappointing, given the small size of the proposed reforms.

The Church of England and the “Golden Age”

At the end of the 16th century, when Calvinist influences were dominant, a period known as the “Golden Age of Anglicanism” began, which spanned over the next century. Under the patronage of the Caroline Divines, a group of theologians and clerics, the Church of England definitively rejected Rome’s claims of primacy and the theological and ecclesiastical systems of European reformers. The classical version of Anglican Christianity tries to avoid confessional tendencies and categorically rejects any form of absolute authority.

The historic (Canterbury) episcopate has been preserved, but it has not been and is not seen as a priestly institution. The Church of England has reserved the right to adapt its mission and teaching, but the changes it intends to make are considered legitimate as long as Scripture is considered the treasure of all things necessary for salvation.

In Anglicanism, the truth must be sought in Scripture and in ecclesiastical authority, the latter being based on the Christian tradition of the first four centuries. These sources are accessed through reason, as a judge and intermediary.

In May 1649, Oliver Cromwell became Lord Protector of England. He was a typical Puritan who, on the basis of his military success (interpreted as a sign of heaven’s blessing), implemented a system of government in which God’s judgement and mercy are put to work in society politically. The Reformation of England was intended to surpass the Reformation of other nations.

This was the basis of a pluralistic religion in England, in which parish churches were run by elders, independents, Baptists, or other Christian denominations. Jews were allowed to live in England, but Roman Catholics and Unitarians were not allowed public religious activities or other manifestations.

However, in the social unrest caused by the wars, radical groups emerged that challenged this religious pluralism and advanced the Puritan vision of a new Jerusalem. These separatist groups were short-lived. A group with a longer history was founded by George Fox (1624-1691) and is known as the Society of Friends or Quakers.

The vision of this group is that if the authority of the pope is to be rejected, then any ecclesiastical authority is superfluous, hence the lack of need for clerics, sacraments, and liturgy in the church. Puritanism never succeeded in consolidating itself into a monolithic movement, and the adherence of one orientation or another to power generated factionalism. The limits of the Puritan spirit were clearly revealed in the sustained persecution of the Quakers.

In the Restoration following Cromwell’s death, the continuity of the organisation on an episcopal line was discussed, considering two models: one Catholic (the dominant one) and the other a modified version. The problem of how to defend against the secular teachings of the rationalist Enlightenment was also raised.

One group that stood out during this period was the “Cambridge Platonists” (1633-1688), who aimed to avoid the rigidity of Calvinist predestination, but also the secular reactions to the Calvinist model. The emphasis on personal devotion and conservative respect for the sources of wisdom of the past was countered by the mechanistic view of nature and human society that would later characterise Anglicanism.[1]

The Church of England expanded beyond the borders of England, especially on the New Continent (North America), where the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel sent about 300 clerics between 1701 and 1776. The transnational development of the Anglican Church took two significant directions.

The first was a result of the obligation in the nineteenth century for every pastor in the Church of England to live within the boundaries of his parish. Although there were exceptions, this rule led to countless initiatives of parishioners, educated people, to establish schools. By the end of the nineteenth century, the whole education system in England was run by the church. Also, wherever the Anglican Church spread, the model of the church and the school was replicated.

The second development is related to the founding of the United States. Having had to fight on the continent against Napoleon, after 1776 England gave up colonialist and imperialist ideals. Instead, the Anglican secular people initiated a process of eradicating slavery. Under the leadership and influence of William Wilberforce, the campaign against the slave trade resulted in its outlawing in England in 1807.

There was a strong concern to redeem the abuses made against the enslaved African peoples. Thus began the nineteenth-century missionary movement. The missionaries went mainly to Africa to spread the Christian faith, education, and trade in order to replace the slave-based economy.[2]

These brief facts provide a clear picture of the role and identity of the Anglican Church in history and society. It is one of those Christian organisations that has the merit of making a significant contribution to the creation of a balanced Christianity, of being missionary motivated and interested in the well-being of society and the human being.

Laurenţiu Moţ explains the historical and theological factors that laid the foundations of the Anglican Church and highlights some of its influences on society and on the development of Christianity.