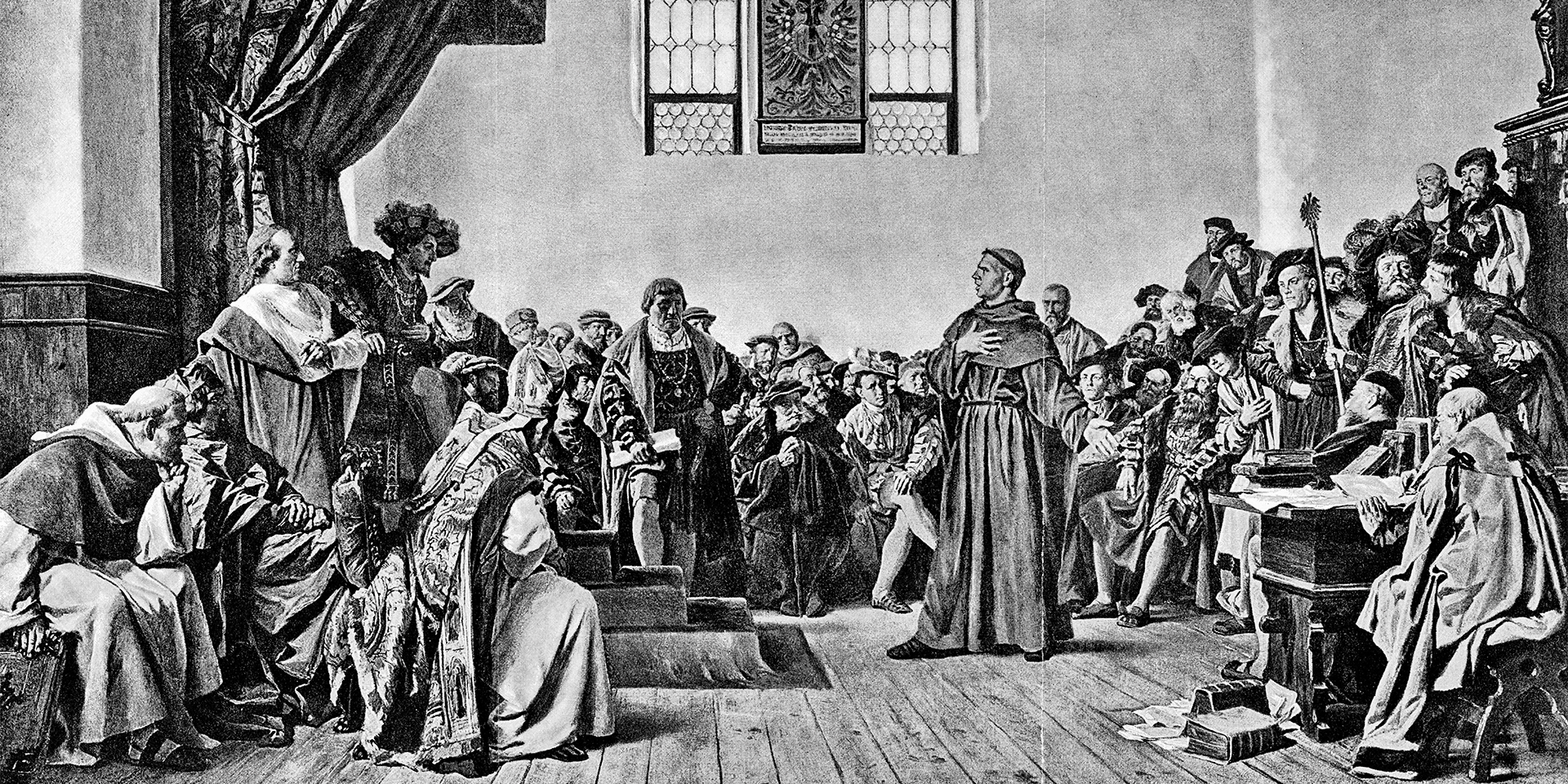

Five hundred years ago, Luther nailed his 95 theses to the door of Wittenberg Cathedral. How are the motives that led to the Reformation viewed today?

Margery Kempe stepped out of the confessional, stumbling like a drunk. It was her third visit to confess her sins that day, and her weeping, hunger, and conscience had affected her balance. This was nothing unusual for her. She went to the church every day, where she prayed fervently, and often in tears, for forgiveness. The way she begged for Christ’s mercy made her known to the entire Catholic community in the town of King’s Lynn, Norfolk, England, but few believed her to be sane. Most were either frightened or disgusted by the woman who had been troubled to the point of paroxysm after her first child was born.

Margery had become so overwhelmed by the feeling of her repulsive sinfulness that she struggled daily and publicly to obtain divine forgiveness. Although she was said to be illiterate, she had memorized Pater Noster, Ave Maria, the Ten Commandments, and several other religious doctrines, and her memoirs, dictated to the priest to whom she confessed at church, are considered the first autobiographical work ever written in English.[1] Some historians say that because of the autobiographical nature of Kempe’s writing, the book is the deepest literary immersion in the life of a middle-class woman in the Middle Ages.

In the fourteenth century, when Margery Kempe lived, only men—more precisely, priests—had the right to interpret God’s Scriptures and actions. Women were allowed to interpret God only in a mystical sense, by heightening their senses—hearing voices, spiritual apparitions, verbal inspiration, or intellectual enlightenment.[2] Therefore, as a medieval subject (limited by lack of education, ignorance, and superstition) and, above all, as a woman, it was in fact almost natural for Margery Kempe to despair over her salvation.

One day she left the confessional so deranged that she began to see devils surrounding her, pawing at her, making her bite and scratch herself. “She knew from the confession that she was not righteous enough to have merited salvation.”[3] The guilt of her own inadequacy made Margery embark on a long, gruelling, and exorbitant tour of several dozen of Europe’s most famous places of pilgrimage. She had heard that indulgences could be bought from those holy places, so she bought such certificates of forgiveness for friends, enemies, souls captive in purgatory, and for herself.[4]

A few decades later, another Catholic believer, this time a German man also overwhelmed by his own guilt before a pure God, would challenge the papers in which Margery Kempe put her faith for salvation. He saw these as representing false doctrines, and malpractice by the church. Martin Luther, the man we are talking about, was able to take a step back, and see the true injustice of selling chances for heaven.

The same Luther took a leap forward, catalysing the multifaceted revolution of the Protestant Reformation. Historians talk about what helped Luther start this spiritual earthquake in terms of “causes” as well as “antecedents.” The difference between these terms is one of substance: Was the Protestant Reformation an inevitable result of the circumstances in which it was born, or not?

If the Middle Ages could “share location”

The most notorious coordinates of the religion of the Middle Ages are the indulgences, which the priests sold to the faithful, and the spiritual licenses, which they claimed free of charge for themselves. But while it is true that, according to the historical report, Martin Luther crystallized his theological indignation from the 95 theses after meeting the infamous monk Johann Tetzel (a skilled indulgences salesman), it is equally true that, in the background of the Reformation, many other factors of different natures intertwined.

In the Middle Ages, as Nae Ionescu wrote in the introduction to Herbert Spencer’s The Man Versus the State, “life flowed in and through the community.” The individual or human personality was missing from the equation. “It is not the lack of individuality, but the lack of awareness of individuality that characterizes the Middle Ages… Between man and God, stood the church,”[5] he said. People could not be saved outside the church, and it was only the church that legitimized the individual, or lent legitimacy to a truth. Without community, the individual had no meaning and no value.

Tradition, collectivism and hierarchy were not only nuclei of the morality of medieval society, but also the basis of the authority of the church at that time. Still, this balance of power began to change, as more and more people left the village for the city. In the city, among other advantages, the effects of easier access to education were felt, and the medievalists who benefited from the cultural contribution inaccessible to those from the countryside became more receptive to new ideas and more inclined to shape their individual identity. Still, cities, which at first seemed like homes of opportunity, suddenly turned into incubators of horror after the “black death” decimated entire generations of Europeans.

The Great Plague killed the majority of townspeople in record time. Stemming from the mid-14th century in Florence, where it was brought by rats on ships that connected the Far East to Europe, the Plague exterminated between 45% and 75% of the population of the Italian citadel in the first six months. In Venice, 60% of the population died in the first eight months. People were defenceless against a threat that doctors did not know enough about and against which they had no defence. Flea bites and lice were frequent, so many did not distinguish rat bites from those of the usual bug bites.

After such a bite, the infection incubated in just a few days (between two to six), and the patient suffered from subcutaneous haemorrhages, which swelled, formed blood clots and led to cell necrosis. The dead cells then poisoned the nervous system, which threw sufferers into an unbearable agony, culminating in death. People in the Medieval age were accustomed to infant deaths, maternal deaths, accidents at work, and had no hope in the abilities of doctors, whose treatments often proved precarious in the face of ravaging infections and fevers. Even so, the plague stunned them, without warning, and only a few escaped unscathed.

The survivors were traumatized by the sinister experience, internalising death as a reality of life. Some historians note the possibility that many became sensibly interested in the afterlife and salvation from sin, precisely because they lived so close to death.

In fact, the religious effervescence of the time had no competition. “More masses for the dead were paid for, more churches were built, more statues of saints were erected, and more pilgrimages were made than ever before,”[6] writes Michael Reeves in The Unquenchable Flame. “Books of devotion and spirituality—as mixed in content as they are today—were extraordinarily popular among those who could read.”

By virtue of their collectivist education, the medievalists nervously sought church, hoping that the answers and hope they needed would come from it. Some of them witnessed the greedy and opulent priests filling their treasuries from the trade in indulgences. Others saw church elites disregarding rules that applied to local priests—such as celibacy—and even turned their institutions into monuments of nepotism. But the reputation of religion seemed to metabolize priestly deviances pretty easily, which then lead to these deviances being generalised in society.

“Certainly people had their grumbles, but the vast majority clearly threw themselves into it with gusto,” writes Reeves. Even profane readings had spiritual messages. See, for example, Dante’s Divine Comedy, which described a special place in hell for corrupt popes. Those who understood its sarcasm believed it was in good taste, a sign that the church could enjoy satire.

“Of course there were corrupt old popes and priests who drank too much before Mass,” Reeves wrote. “But the fact that people could laugh at them showed how solid and secure the Church appeared. It looked like it could take it. And the fact that they wanted to prune the dead wood only shows how they loved the tree.”

Today, the Catholic Church partially admits to the existence of bad apples. And this institutional perspective broadens the spectrum accessible to the simple Christian. The New Advent Catholic Encyclopaedia recognizes the ravages of clerical corruption but places it within the context of a millennium of undisturbed Catholic hegemony, established with both good and evil in its foundations.

“With the ecclesiastical organization fully developed,” the authors write, “the activities of the governing ecclesiastical bodies were no longer confined to the ecclesiastical domain, but affected almost every sphere of popular life.” This historical consensus, therefore, validates the corruption of the clergy of that period, the differences referring, on the one hand, to the extent of this phenomenon, and on the other hand, to the nature of its causes.

According to the encyclopaedia mentioned, corruption was supposedly a rather exceptional manifestation, which was internalized imperceptibly: “Gradually a regrettable worldliness manifested itself in many high ecclesiastics. Their chief object—to guide man to his eternal goal—claimed too seldom their attention, and worldly activities became in too many cases the chief interest. Political power, material possessions, a privileged position in public life, the defence of ancient historical rights, earthly interests of various kinds were only too often the chief aim of many of the higher clergy.”

As a result, many church leaders conveniently made friends with lay leaders, thus paving the way for abuse. In fact, the authors write, “many bishops and abbots…bore themselves as secular rulers rather than as servants of the Church… Luxury prevailed widely among the higher clergy, while the lower clergy were often oppressed.”

However, when he says that “as to the Christian people itself, in numerous districts ignorance, superstition, religious indifference, and immorality were rife,” the Catholic author reaches an even softer spot. The “ignorance, superstition, religious indifference, and immorality were rife” because the people were kept in this state by a combination of factors favourable to the authority of the Church.

Among them, frequently encountered on lists of reproaches, is the officiating of services in Latin, which the common believers could not understand, but also the absence of Scripture translated into the language of the people. This is the context in which historians note the huge difference that the Reformers made when they started circulating vernacular religious writings, and translated the Bible from ancient languages into modern ones.

The spread of Protestant ideas happened at a rate that was difficult to stop, due to the invention of printing. By 1523, no less than 1,300 pamphlets signed by Martin Luther had seen the light of day. A calculation made by historian Hans J. Hillerbrand in The Protestant Reformation[7] estimates that if each of these pamphlets was reproduced 750-800 times, we are speaking of a total of one million copies. “Sermon on Indulgence and Grace,” the most popular of Luther’s writings, was published in German in 1518 and republished 14 times in 1518, five times in 1519, and four times in 1520. “We tend to overlook the dimensions of this flood of propaganda,” Hillerbrand wrote.

Just like the intellectuals of the time, connected to the Renaissance tendency to bring back to life the values in the works of the ancients, the reformers ignited the interest of believers in the writings of the first fathers of Christianity. The voice of the apostle Paul begins to be heard again on the subject of the doctrine of salvation, so present in his writings. And the reformers’ inclination to reassert the primary meaning of the words of Scripture (see the curative effort of Erasmus, who wanted to free the Word from Catholic interpretations) resonated deeply with people’s desire to know that their souls could be sheltered from the eternal fires of hell, even the temporary ones of purgatory.

If during all this time the ecclesiastical elites seemed more concerned with securing their positions of authority, the reformers seemed not only eager but also qualified to respond to the deepest turmoil of the faithful. There are different perspectives on this. Catholic historian Johann Peter Kirsch says that although it was crushed by corruption, the Church was still a largely functioning institution, which was hit harder by the Reformation than by dishonesty and the awareness of this dishonesty: “The doctrine of the Church, it is true, had remained pure; saintly lives were yet frequent in all parts of Europe, and the numerous beneficent medieval institutions of the Church continued their course uninterruptedly.”

The Calvinist historian James R. Payton Jr., however, outlines a picture of the medieval theological environment that not only lacks doctrinal purity but also shows a confusing and contradictory variety of opinions with doctrinal pretences.

Payton summarizes that, “by the end of the fifteenth century, these issues included the questions of how badly human nature was affected by original sin (completely depraved, partially depraved, somewhat wounded), how we are counted righteous in God’s sight (by faith alone, by faith plus works, by works alone), what religious authority we must follow (the Scripture alone, the church hierarchy’s teaching alone, the Scriptures as taught by the ecclesiastical hierarchy, conscience), how the sacraments worked (virtually automatically, only if accepted in faith, or basically as symbols to stimulate faith) and the nature of divine predestination (foresight, divine decision, refusal on God’s part to know).”[8]

Thus, as a result of the various philosophical affinities manifested by the members of the Catholic theological elite, the paths of theological interpretations have been divided since the fourteenth century in ways that, obviously, can no longer intersect with each other, nor with the interests of ordinary Christians.

The reform of the stubborn

The Reformers didn’t enter this framework with new theological approaches or with truths never explored before, but with answers to the truth-seeking of ordinary Christians.

Therefore, when some or all of the Reformers opposed the doctrine of purgatory, private judgment, or the cult of the Virgin Mary, when they challenged the role of intermediary of the saints and the reality of transubstantiation, and also when they denied the authority of the pope, the work of the Reformers was viewed as a simplification of the message of Christianity by those who received it; a purification of all historical additions and distorted reinterpretations that skewed Christianity’s ability to speak directly to the heart of the believer.

Of course, this summary is not consensual. Catholic Kirsch accuses “the variously hostile spirit of the civil powers, fostered, and heightened by several elements of the new order… in many parts of Europe [to be the cause of] political and social conditions which hampered the free reformatory activities of the Church, and favoured the bold and unscrupulous, who seized a unique opportunity to let loose all the forces of heresy and schism so long held in check by the harmonious action of the ecclesiastical and civil authorities.” However, history tends to contradict, at the very least, the descriptions that contain references to harmony.

After the Great Schism, the Catholic Church went through a real void of authority, caused by a surplus of popes. Specifically, for a period of several decades (1378-1415), Western Christianity experienced a double and rival papacy, with one pope in Rome and one in Avignon disputing their legitimacy. The conflict fuelled by blatant corruption had cast the papacy into disfavour, generating what history has diplomatically recorded as “anticlerical sentiment.”

If the believers and the clergy despised each other, this contempt was passive. Against the Reformers, however, the clergy harboured an active contempt, captured by Max Weber in Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism, by formulating a biased rule: “punishing the heretic but indulgent to the sinner.”[9] The clergy were corrupt, and this was a sin. But the Reformers were forcing a change—and this was a heresy.

The Catholic Church could not accept the Protestant Reformation as it integrated internal calls for “reform in head and members” (reformation in capite et in membris), because, unlike the latter, the reformation of Luther and those like him disputes the sources of authority of the Catholic Church. When they raised Scripture as their sole authority, Protestants set aside philosophers, the Catholic elite, popes, and priests, and when they placed Scripture in the hands of believers, they eliminated any ecclesiastical mediation between man and God.

The Church could not tolerate such a prospect, because it undermined its edifice of power—civil power. The desire of church leaders for ecclesiastical power was aimed at political influence and securing their own pockets. However, an unanticipated consequence of the elimination of ecclesiastical power from the conscience of the now Protestant Christian was, as Weber said, “the substitution of a new form of control for the previous one. It meant the repudiation of a control which was very lax, at that time scarcely perceptible in practice, and hardly more than formal, in favour of a regulation of the whole of conduct which, penetrating to all departments of private and public life, was infinitely burdensome and earnestly enforced”.[10]

Was it worth the price? The fact that we admit that in order to restore the dignity of conscience and to grant access to religious education, a price needed to be paid, and the fact that both believers[11] and reformers[12] paid it, is in itself an argument that the Protestant Reformation did not take place naturally, stemming from the social, religious, political, and cultural circumstances in which it was born. Even if we could simplify the entire historical context of the Reformation until we reduced it to an exhaustive account of causes and effects, we would still have to stop at the free will of the key figures in the grand scheme of things.

The more we admit that these characters are many (not just Luther but also many other reformers), the more we realize the many other places where the Reformation thread could have snapped. And if we focus on the reductionist version, putting all the credit on Luther’s shoulders (Why would we do something like that?), we would have to admit that a simple retraction could have demolished the entire Protestant scaffolding. Surely, Luther’s words, “Here I stand, I can do no other,” were not a resigned realization of divine determinism. They were a choice. We can therefore say that the Reformation, although deeply necessary, was far from progressing out of necessity.