Claiming justice is history’s refrain, and it has a significant echo in the Bible. We all dream of a happy ending and a fair judgement as soon as possible. Heaven itself is surprised that God has delayed His holy justice. While some wait for it, others quash even the very thought that it might come.

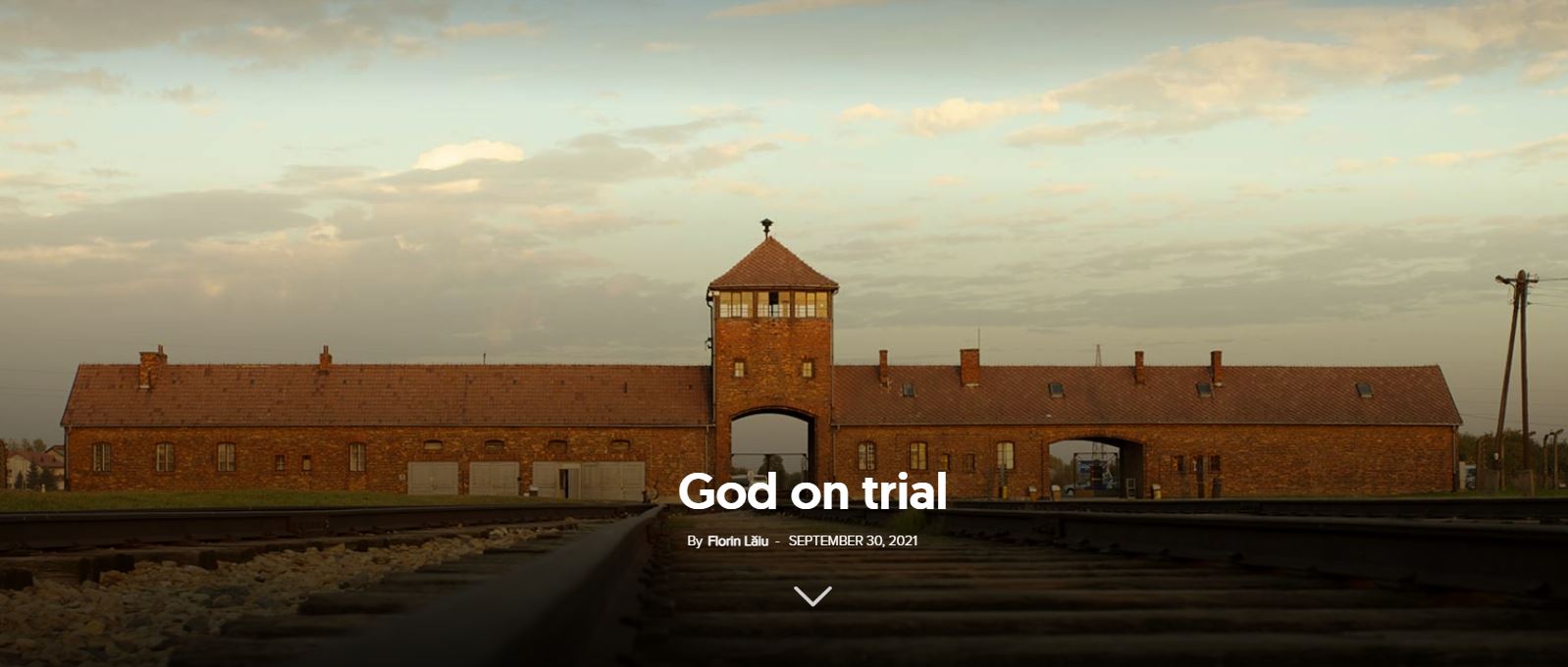

Throughout sacred history, God has sometimes intervened and meted out justice, not necessarily as we might expect, but in His way, a way that disturbs us and for which He has promised to give us an explanation someday. Other times, God has delayed His justice. The reader must certainly have heard of the Nuremberg Trials. This is only a shadow of the future judgement, when even the brave Allies will be held accountable for sins no one has yet held them accountable for.

Judgement begins with those close to you

In this gospel of ours, the first people who were punished by God were those who, having received the most blessings, still broke the covenant with Him:

“There was a landowner who planted a vineyard. He put a wall around it, dug a winepress in it and built a watchtower. Then he rented the vineyard to some farmers and moved to another place. When the harvest time approached, he sent his servants to the tenants to collect his fruit.

“The tenants seized his servants; they beat one, killed another, and stoned a third. Then he sent other servants to them, more than the first time, and the tenants treated them the same way. Last of all, he sent his son to them. ‘They will respect my son’, he said. But when the tenants saw the son, they said to each other, ‘This is the heir. Come, let’s kill him and take his inheritance.’ So they took him and threw him out of the vineyard and killed him. Therefore, when the owner of the vineyard comes, what will he do to those tenants?” [1] (Matthew 21:33-40).

The truth is that God has sometimes allowed great injustices in the world. However, the end of this significant story shows that justice is inevitable.

When asked by Jesus, “What will the owner do with those tenants?”, the listeners—the high priests and elders—pronounced their own sentence, before realizing that this was aimed at them (“He will bring those wretches to a wretched end”).

The sentence was executed in the same generation, in 70 AD, over Jerusalem—the city that had crucified the Son of God. But the famous curse of Good Friday—“All the people answered, ‘His blood is on us and on our children!’”—also awaits the Christians descending from that ungrateful generation that crucified Jesus. Just as we are the children of Israel only by faith and love,[1] so we become spiritual sons of Caiaphas through unbelief and hatred.

Since the Fall, the curse is our share. The curse, however, is either an educational punishment (Genesis 3), with blessings at its core, or just a foreshadowing of the last reckonings. The curse’s reach extends to the fourth generation, often neutralized by God’s grace, which extends to the thousandth generation (Exodus 20).

Justice and grace in history and on Judgement Day

Beyond God’s indulgence, however, final judgement cannot be fooled by “fig leaves”—by appearances. Jesus illustrated this idea through the parable of the royal wedding:

“The kingdom of heaven is like a king who prepared a wedding banquet for his son. He sent his servants to those who had been invited to the banquet to tell them to come, but they refused to come. Then he sent some more servants and said, ‘Tell those who have been invited that I have prepared my dinner: My oxen and fattened cattle have been butchered, and everything is ready. Come to the wedding banquet.’ But they paid no attention and went off—one to his field, another to his business. The rest seized his servants, mistreated them and killed them. The king was enraged. He sent his army and destroyed those murderers and burned their city.

“Then he said to his servants, ‘The wedding banquet is ready, but those I invited did not deserve to come. So go to the street corners and invite to the banquet anyone you find.’ So the servants went out into the streets and gathered all the people they could find, the bad as well as the good, and the wedding hall was filled with guests.

“But when the king came in to see the guests, he noticed a man there who was not wearing wedding clothes. He asked, ‘How did you get in here without wedding clothes, friend?’ The man was speechless. Then the king told the attendants, ‘Tie him hand and foot, and throw him outside, into the darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.’ For many are invited, but few are chosen.” (Matthew 22:2-14)

The heralds were not empowered to discriminate, but had to invite everyone. The “nobility” or “wretchedness” of those on the road could be inferred just by looking at their clothes.

It is no coincidence that the “evil ones” are the first to be mentioned in the original text (“the bad as well as the good”), because most of those who came were have-nots. Illustrated here is the universal invitation of the gospel, which is first for the lowly.[2]

But the emperor seems to have taken every precaution to make the guests feel good, not to enter the banquet as they were, coming from the stables, all dusty and sweaty. Being taken off the road, one understands that the host had made preparations to receive them so that no one would feel too bad or too good. A wedding garment which, according to the custom of the time, was a white, clean, festive robe, was prepared for everyone.

Accepting the invitation to the banquet of the gospel implies accepting a new status and character: “…for all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ”.[3] No other distinctions, no gentlemen’s and servants’ clothes. Only the garment of the joy of being in God’s favour, of being accepted and made worthy. However, individuals with an excess of “personality” do not wish to be treated like everyone else; to be “enrolled”, to wear a “uniform”.

The parable culminates with a review of the guests. Among the guests, the emperor sees from the beginning a gentleman who had violated royal protocol. As the feast clothes were white, it was easy to spot colourful clothing. I wouldn’t be surprised if the intruder had sat above the salt. He was probably asked by the other guests about his outfit, but he would have probably had reasonable explanations and even convinced some. Who knows? Perhaps others had followed his example as well.

A more colourful coat was a mark of social distinction.[4] It is difficult to understand how this intruder slipped into the room going past a serious royal coat check.

Apparently, he had managed to impress everyone with his coat and rhetoric. The emperor’s confrontation with the distinguished gentleman is as brief as it is impressive. His Majesty’s astonishing question is an echo of that posed to the first sinners (“How could you do such a thing?”, Genesis 3). This is where the motif of the missing clothes and the clothing with inadequate justifications appears for the first time.

The emperor does not address him as “Friend!”, as some translations suggest. The clever gentleman was not a phílon (“friend”, James 2:23), whom you could call in the middle of the night to help you,[5] but a hetáiros (“fellow”, Matthew 26:50), a simple “guy”, “monsieur”, “comrade”. It is one thing to be a part of God’s company for a while, but it is another to be His friend.[6] The distinguished guest can no longer mumble any explanation.

All the previously prepared justifications now seem ridiculous. And the punishment is appropriate. Did you refuse the uniform of joy? You are taken and bound to where you belong: outside, in the dark, where you will bitterly regret the stupidity of risking eternal joys for the sake of a moment’s whim.

In the parable, only one guest is caught off-guard. He might just be the first to be discovered. With only one rejected candidate, the judgement has a very optimistic result! However, if that particular candidate is me or you, the statistics don’t matter quite so much anymore.

Jesus even states that, at the Last Judgement, the percentages are reversed: many have slipped into the Church, but few will remain in the wedding hall. That is why a judgement (testing) of the “house of God” is made, now, before the coming of Jesus and the judgement of the whole world.[7] The late Lutheran theologian Helmut Lamparter wrote: “When Paul says that ‘the Lord’s people will judge the world’ (1 Corinthians 6:2; cf. Matthew 19:28) we must conclude that the judgement of ‘the Lord’s people’ and the judgement of the ‘world’ cannot be one and the same action.

“Just as the resurrection of those who belong to Christ precedes the general resurrection of the wicked dead people, so the judgement of believers precedes the judgement of unbelievers. The judgement of the Church is not identical, neither in time nor in content, with the judgement of the world”.[8]

It’s just as the apostle Peter, the one holding the true keys, said long ago: “…and if it begins with us, what will the outcome be for those who do not obey the gospel of God? And, ‘If it is hard for the righteous to be saved, what will become of the ungodly and the sinner?’” (1 Peter 4:17-18).

Let’s leave the final sentence to God

As for the application of justice here and now, much harm has been done over the centuries when God’s kingdom has been mistaken for the state of the faithful, as in Islam. Under the Church’s direction, honest people, who understood religion differently, began to lose their civil rights. This classic style of the Church of bringing about justice has created more problems than it has solved:

“The kingdom of heaven is like a man who sowed good seed in his field. But while everyone was sleeping, his enemy came and sowed weeds among the wheat, and went away. When the wheat sprouted and formed heads, then the weeds also appeared. The owner’s servants came to him and said, ‘Sir, didn’t you sow good seed in your field? Where then did the weeds come from?’ ‘An enemy did this,’ he replied.

“The servants asked him, ‘Do you want us to go and pull them up?’ ‘No’ he answered, ‘because while you are pulling the weeds, you may uproot the wheat with them. Let both grow together until the harvest. At that time I will tell the harvesters: First collect the weeds and tie them in bundles to be burned; then gather the wheat and bring it into my barn’” (Matthew 13:24-30).

But why not nip the weeds in their buds? Why not purge the world of heretics, sectarians, radicals, atheists and all those who hold a separate opinion? Because, as the Lord told us, we often do not know what we are doing. We can see heresy where there is a seed of righteous faith, and vice versa. We can see social danger where there is just a separate and critical opinion. Only when the seeds bear fruit can their true character be distinguished. We will certainly have dizzying surprises “on that day”.

“Once again, the kingdom of heaven is like a net that was let down into the lake and caught all kinds of fish. When it was full, the fishermen pulled it up on the shore. Then they sat down and collected the good fish in baskets, but threw the bad away. This is how it will be at the end of the age. The angels will come and separate the wicked from the righteous and throw them into the blazing furnace, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth” (Matthew 13:47-50).

There are two phases of the gospel: the missionary phase and the critical phase. In the first phase, the Christian message must reach as many as possible. In the second phase, the “discriminations” begin, but they are made by the angels themselves, not the saints, because the saints could also throw away a few of the good fish.

Judgement criteria

The Lord’s parables reflect a specific answer to the judgement criteria. It all comes down to the character of Jesus. Through the symbol of the wedding garment, this is a gift that we voluntarily appropriate. The gospel catches us all in its trawl, but if judgement surprises us in the same state as we were when we were caught—frogs, jellyfish, or starfish—we are thrown back. There is enough diversity here, and so many good fish species. The good seeds can be diverse, but not diversionary: even if at first they are mistaken for wildness, they will become more and more different from the devil’s weeds.

The most sensitive account of the criteria is found in the parable of the sheep and the goats (Matthew 25:31-46). The sins of the goats, for example, were not their high leaps, their spunky gaze, or black fur. They are moved to the left, the Greek expression using, in this case, a euphemism that literally means “With a good reputation”! Do you remember that elegant gentleman who was caught without a formal coat?

The goats did no harm to the Lord, and perhaps their religion even honoured His remembrance and reputation. Their misfortune was that brotherly love was so important in the eyes of the Lord that other religious aspects are not even mentioned in the parable.

You may also like:

If you have forgotten mercy, then the right faith, the holy sacraments, the commandments, the feasts, the saints, the unholy people, the fasts, and divine services—all are irrelevant at the judgement. Mercy is the true badge of the Saviour, the true religion. We are not talking about the visceral mercy of everything that moves, but about being of one mind with Jesus’ brothers. Among them, there are some who are so small that they cannot be seen; so small that you have to look for them; so insignificant that no one would notice them.

Some are already living this religion of service naturally, without thinking of an eternal reward. Others are just skipping through the fields, forgetting the Emperor’s expectations. Some are hidden in Christ, others are still hiding behind Christ. Thank God, the big draw hasn’t yet been made. However, it won’t be long before it is made, because we are already, ourselves, in the midst of the judgement time.