Footballers are often in the headlines for their off-field antics more than their on-field achievements. So, it is no real surprise that the greatest story to come out of the AFL is not about a nail-biting final or freakishly skilled player. By many people’s assessment the hero of this story should never have been remembered. Sir Douglas Nicholls was vilified for his race, scoffed at for his height and overlooked by many, despite his pioneering achievements. Yet, there’s never been a man that has contributed so much both on and off the field.

Nicholls is a deserving icon of Australian football—but he is much more than that. His contribution to the game, care for the community and advocacy for his people truly represent what is perhaps the greatest untold story of the game—if not the nation.

The boy from Cummeragunga

Born in 1906 at Cummeragunga on the land of the Yorta Yorta people, Nicholls’ childhood was a mix of freedom and trauma.

As a young boy, his afternoons would be spent honing his football skills bootless on the paddocks close to the Indigenous mission he and his family called home.

It was the era of the Aborigines Protection Board, and the many oppressive policies of the Australian government. It was here that he witnessed his sister’s forced removal by government authorities.

“They just came in and ruthlessly threw our girls into the car and their mothers hung to them,” he recalled. “I can see my mother hanging on to my sister, 16 years old—they threw her in the car.”

His sister was sent to Sydney as a domestic help. A number of years later she returned pregnant before passing away at just 26.

Nicholls’ grandson Gary Murray recalls this harrowing experience as one of the things “that drove Grandfather in trying to do the right thing by everybody”.

At the age of 14, Nicholls was forced to leave his home and school to find work as a labourer. It was a move that would eventually open doors for the young, football-loving boy. But it also exposed him to a new raft of discrimination.

“A champion in everything”

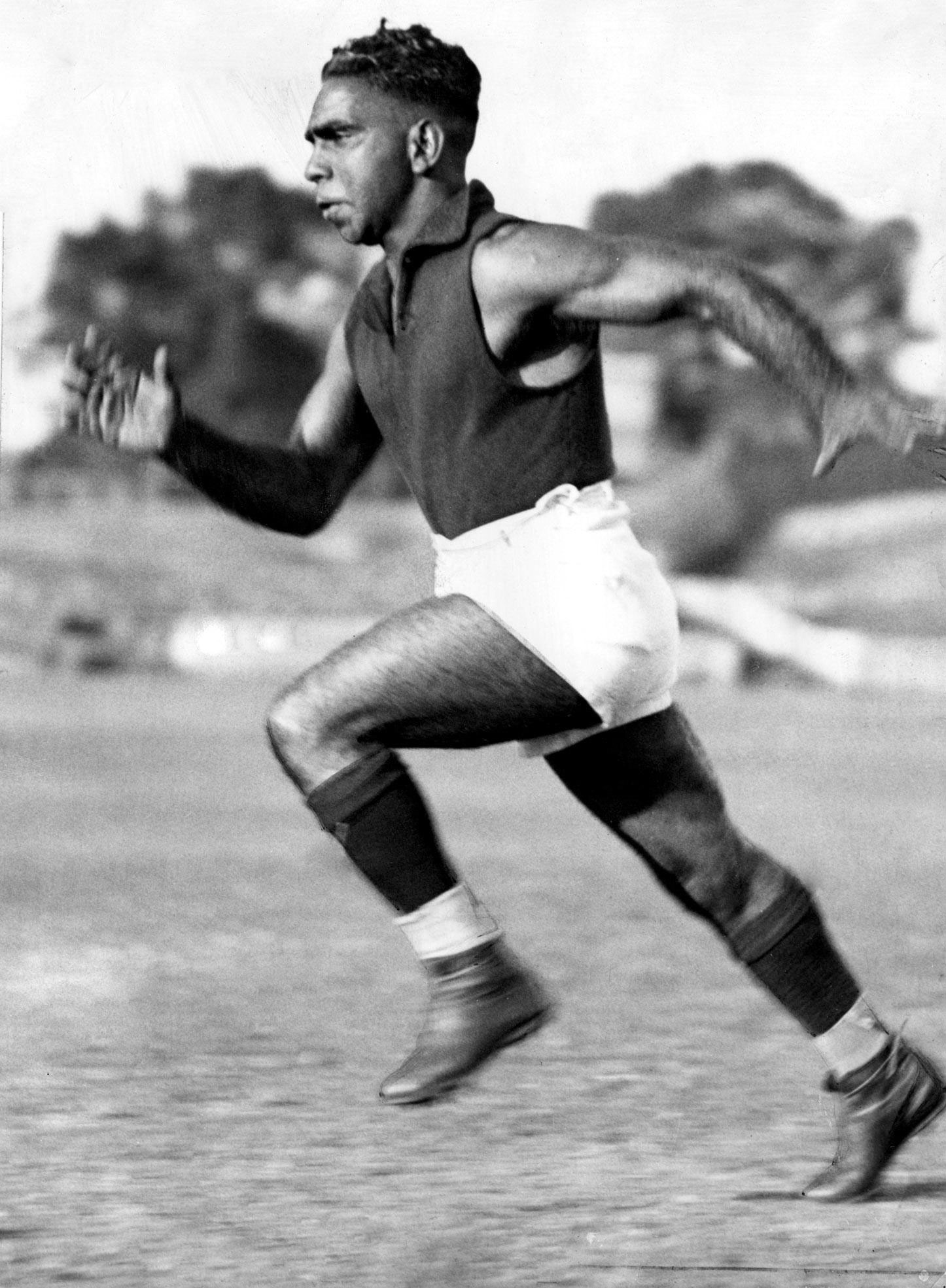

Despite being just 158cm tall (the second-shortest man to ever play in the AFL), Nicholls was muscular and lightning fast. His natural athleticism meant he found success in professional running, boxing and football.

“He was a champion in everything—all at the one time,” his grandson Jason Tamiru remembers. “It’s totally mind-blowing for me.”

But it was his love of the ball that kept drawing him back to the turf.

After moving to Melbourne from regional Victoria, Nicholls began his football career as a curator with the Northcote Football Club. But it wasn’t long until his talents were noticed and he was approached by Carlton to join their playing squad. He also spent time playing for Fitzroy throughout the years.

By the time he hung up his boots, he had been named “best and fairest” twice and appeared in three grand finals, including in a championship winning side in 1929.

At the time, Nicholls was the only Aboriginal man in the football league. It was a fact that brought him plenty of attention—much of it unwanted and unwarranted.

A dark day in blue

An old black-and-white recording of Sir Doug Nicholls captures his reflection that throughout his football career, “I was never conscious of my colour. I felt that I was their equal.”

The comment likely says more about his character than it does the reality of his footballing experience. There are countless examples of times in which both the words and actions of others reminded Nicholls that they did not consider him their equal.

Just one sad example of this occurred in the change rooms at Carlton. Following a game, Nicholls asked for a rub down—something which was offered to every player to aid their recovery.

But instead of a soothing massage, he received a stinging response: “No, we’re not going to rub you down because you stink.” His daughter Pam Pederson recalls that, “Dad carried that a long time—but he hardly spoke about it He must have been too sad.”

In recent years, Carlton football club have acknowledged the mistreatment that occurred and have strived to make amends. But for every incident addressed and apologised for, there are likely 10 or more that have gone unaddressed.

Fighting for the right

Following his football career, Nicholls went on to become a pastor at the Aboriginal Mission Church in North Fitzroy where he preached clear Christian messages. His congregations often left challenged with a single vision—that as a people of faith, everyone should be making a contribution to the community. It was a message he preached even more loudly with his actions. The trauma of his childhood, along with lifelong experiences of discrimination inspired him to become involved in Aboriginal affairs.

His grandson Gary Murray remembers Nicholls saying, “To get a tune out of a piano you can play the white notes and you can play the black notes, but to get harmony you’ve got to play both”.

It was a message Australia needed to hear. He, along with his wife Lady Gladys Nicholls, spent months travelling Australia to support their people and speak up for Aboriginal rights. There is no doubt that the pair played a pivotal role in securing overwhelming public support in the 1967 referendum where 90 per cent of Australians voted “yes” for Indigenous rights.

Lady Gladys was also instrumental in bringing Aboriginal affairs into the spotlight. Among other things, Lady Gladys was a founding member of the National Council of Aboriginal and Islander Women and established a hostel for Aboriginal girls in Northcote (now the Lady Gladys Nicholls Hostel).

Together, they both worked tirelessly to improve conditions for their people in Melbourne, across Victoria and around the country. And their legacy lives on to this day.

Everything a footballer should be

While Sir Doug Nicholls is often called a “footballer”, it minimises so much of what this great man did, said and stood for.

He was a pastor, an activist, the first Aboriginal Father of the Year and the first Aboriginal state Governor (South Australia). He held an audience with the Pope, was the King of Moomba and remains the only Australian-rules footballer to be knighted.

Every year, the AFL pays tribute to this great man and footballer by hosting the Sir Doug Nicholls round.

While Nicholls was a champion footballer in his own right, his life demonstrated that the true greats of any code contribute much more than just their athleticism.

Until the day of his passing in 1988, Nicholls remained a beacon of life and hope for many people—Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal alike.

His friends and family remember that even in his old age people would come up just to shake his hand. “As soon as you shook his hand that was it,” says Gary Murray. “You knew you were safe. You were with a man of culture, a man of God, and that was really important to people.”

On and off the field, Sir Doug Nicholls embodied a true champion. He pursued personal excellence, served whole-heartedly and stood tall in the face of injustice.

His daughter Pam Pederson perhaps summed up his legacy best when she said, “He was everything a footballer should be—he was perfect.”

Braden Blyde is a freelance writer based in Adelaide, South Australia. When not writing, Braden can be found riding bikes or getting outdoors with his family. A version of this article first appeared on the Signs of the Times Australia website and is republished with permission.