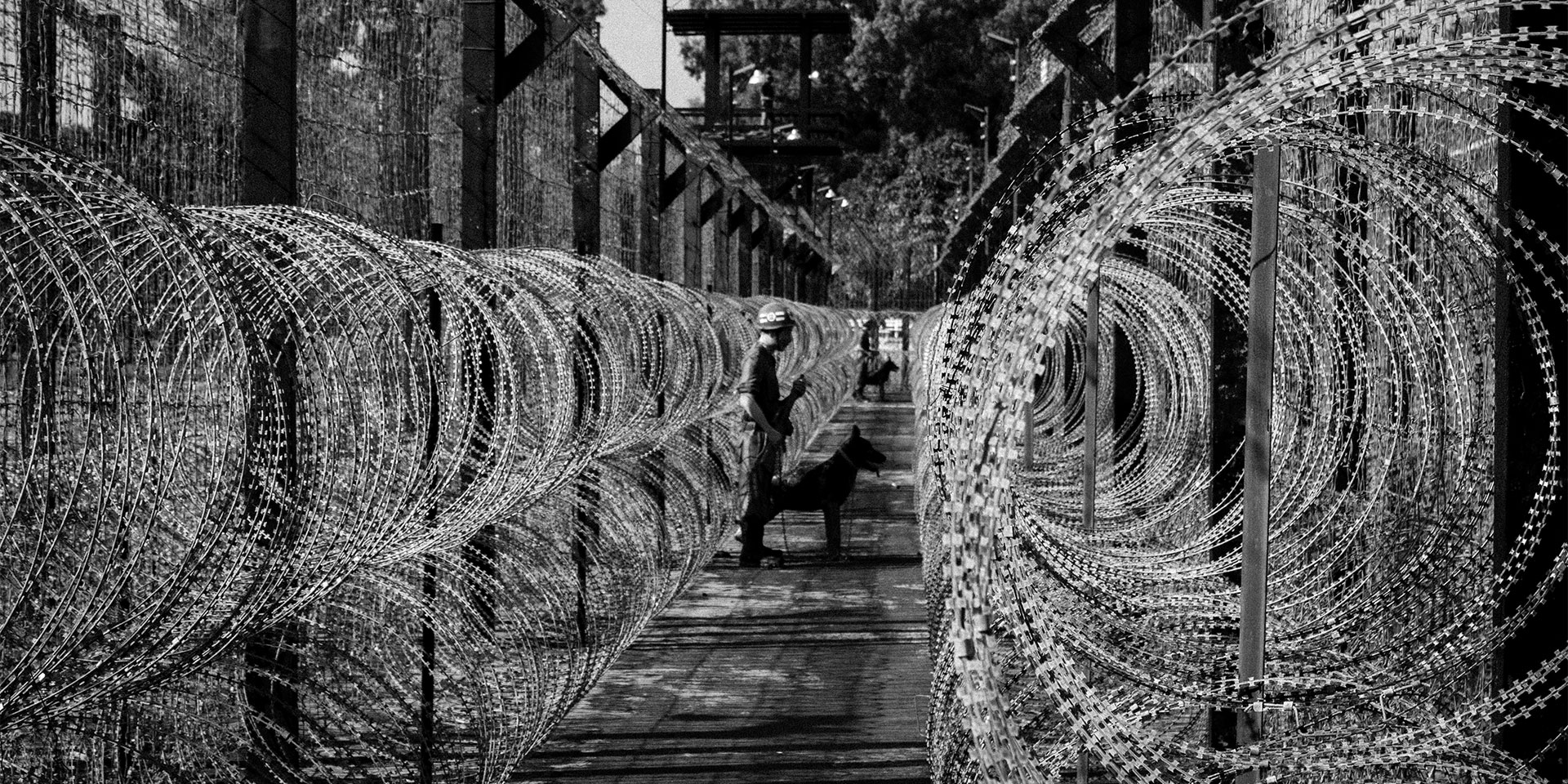

Rape, torture, extrajudicial executions, and starvation are common practices in the North Korean prison system, dehumanising detainees to the point where they believe they deserve this treatment, according to a report published by a human rights monitoring body.

North Korea has always denied allegations of human rights violations, but the testimonies of those who have managed to escape the country in recent years are truly heart-wrenching. While the lives of ordinary citizens seem to be grim (and they really are), those who end up behind bars live a real hell.

“I felt like an animal, not a human,” says Lee Young-joo, who was arrested for illegally crossing the border to China in 2007. In her cell, Lee Young-joo was forced to sit crossed-legged and with her hands on her knees, and was not allowed to move for up to 12 hours a day. Any attempt to communicate with fellow inmates was severely punished, she had limited access to water, and her food ration was limited to a few ground corn husks. Sentenced to three and a half years in prison, the woman quickly learned that there is only one way to increase her chances of getting out of prison alive: “When you go into these places, you have to give up being human to endure and survive.”

Young-joo is one of the people interviewed as part of an investigation carried out by the NGO Korea Future regarding human rights violations in the North Korean prison system.

Published last month, the report manages to give the most accurate picture yet of life inside the prison system of North Korea, which remains one of the most repressive states in the world. The organisation’s investigators gathered data for the report not only from interviews with 269 survivors, witnesses and perpetrators of abuses who managed to flee the country, but also from official documents, satellite images, architectural analysis, and digital modelling of penitentiary units (mapping 206 detention units from each province of the country).

The investigation proves that “even ten years after the UN established a Commission of Inquiry there still is systematic and widespread human rights violations” within the prison system of North Korea, said Kim Jiwon, an investigator with the Korea Future organisation. The authors of the report claim that the abuses are committed by both prison staff and high-ranking officials and call for investigations and prosecution of the abusers.

Several types of camps and solely one reason for their existence

As early as 2014, a UN report showed that Pyongyang was sending political prisoners to camps known as kwalliso to suppress any kind of dissent, and that hundreds of thousands of political prisoners had died in these camps in recent decades due to atrocities that are difficult to describe.

Similar treatments are systematically applied in ordinary prisons (called kyohwaso), but also in detention centres and investigation offices, say the representatives of the Korea Future organisation, who claim that political prisoners are placed in ordinary prisons as well, where abuses can equal or even exceed those in the kwalliso camps.

The North Korean penal system does not aim to prevent recidivism or maintain public safety; its sole purpose is to “isolate persons from society whose behaviour conflicts with upholding the singular authority of the Supreme Leader, Kim Jong Un.”

Inhumane treatments, common in the North Korean prison system

Korea Future has documented over 1,000 cases of torture and inhumane or degrading treatment, hundreds of cases of rape, and other forms of violence. Beyond the statistics, the report also presents cases of people arrested for the crime of having attempted or succeeded in crossing the border.

A woman in her thirties managed to flee to China, but was arrested (while two months pregnant) and sent back to North Korea, where she was accused of crossing the border illegally and subjected to torture during pre-trial detention. When she was seven or eight months pregnant, she was taken to a hospital, where the chief gynaecologist performed a forced abortion on her, by injecting her with a substance that induces premature labour. After the induced labour, the woman did not deliver the placenta, but received no medical attention, so the guards, who had witnessed the entire procedure, were left to “help” her.

The next day, the detainee was sent to a detention centre, and the day after she was transferred to one of the re-education camps, where she was immediately subjected to forced labour for over 10 hours a day.

A man in his forties, who helped several North Koreans leave the country, was subjected to torture by means of the denial of food while detained in the Kaechon camp. During his detention, the prisoner was subjected to forced labour, and received a ration of 120 grams of corn only on the days when he met his daily labour quota. When he did not meet the daily quota, he was fed 80 grams of corn mixed with twigs, corn husks, and fragments of stone per day. In one month, the man lost weight, from 60 kilograms to 37 kilograms. To supplement his meals, he trapped and consumed insects and small rodents. During his nearly eight years of detention, the man estimates that 980 of the 3,000 prisoners in the Kaechon re-education camp died from causes related to starvation and malnutrition.

The stories of the survivors are very difficult to listen to, says Kim Jiwon from Korea Future, emphasising the staggering effect the treatment suffered by the detainees has had on them: their treatment had been so dehumanising to the point where many “just didn’t have the concept of torture.” Because they had been repeatedly told that they had done bad things, their minds had accepted the idea that they deserved to be punished for being bad people.

Many of those who manage to leave prison do not realise that their treatment was abusive, cruel, or inhumane, because they have no knowledge of human rights and believe that this is how the system works: if you do something wrong, you deserve the punishment you get, says James Heenan, representative of the UN Office for Human Rights in Seoul.

Sexual violence against women, part of the “normality” in prison and outside of it

The click of the key twisted into a lock by the guard’s hand was the most horrifying sound ever heard, says Yoon Mi-hwa, who was detained in 2009 in one of the re-education centres for trying to flee the country. Every night, the cell door would open, and a guard would choose a female prisoner to force her to leave with him and be raped.

North Korean women are subjected to constant sexual violence by government officials, prison guards, investigators, police, prosecutors, or soldiers, according to a report published in 2018 by Human Rights Watch organisation. The report documents many acts of sexual violence, showing that it is already common in everyday life. And not just in the prison system.

Oh Jung-hee sold clothes at the market stall until 2014, when she left the country, and says that it was quite common for market guards to ask for bribes, sometimes in the form of coerced sexual acts, and that women were often raped. The woman told Human Rights Watch that she has been a victim many times and that a woman cannot avoid abuse unless she is protected by a man with power and financial resources (usually her father or husband). Women are commonly considered sex toys, and Oh Jung-hee confesses that she never dared to even think about reporting these abuses.

Other North Korean women have said that the police do not consider sexual violence a serious crime and that reporting sexual abuse to the police is almost inconceivable. There can be unwanted repercussions, which is why family members warn victims not to report rape or sexual harassment to the authorities. According to witnesses interviewed by the humanitarian organisation, the government does not provide any psychosocial support services for victims of sexual violence (moreover, there is a strong stigma attached to seeking the services of a psychologist or psychiatrist, in general). Also, former medical personnel who managed to leave North Korea say that there is no protocol for medical treatment and examination of victims of sexual violence.

Victims do not speak up because there is no one to listen to and support them. Sexual violence has become so common because men do not consider their actions wrong and women are forced to accept this treatment. It’s a “normality” that leaves deep traces, because, as Oh Jung-hee says (her words appearing in the title of the report carried out by Human Rights Watch), “sometimes, out of nowhere, you cry at night and don’t know why.”

Carmen Lăiu is an editor at Signs of the Times Romania and ST Network.