The Great Reformation was not a simple schism within Western Christianity. It was not just a religious and political movement. The Protestant Reformation, with its particular spirit and principles, was, first and foremost, a return to the true source and values of Christianity—an attempt to restore.

Despite the imperfection of this restoration process and the problems that restorationism generally raises, the Reformation was, above all, an effort to clear the name of ancient Christianity, a courageous and clear signal, and a return to Scripture.

Naturally, the historical Eastern and Western church, which were subordinated to Rome and Constantinople, rejected the Reformation, for various reasons. The Reformation was the “axe [of John the Baptist] planted at the root of the trees” of the Imperial Church[1], and such a message could hardly be accepted by dry Christianity, whose spirituality especially lay in human exercises of subordination, in mystical adventures, superstitious faith, sacred magic, and pragmatic materialism.

In this article we will defend the Reformation as an authentic, lucid, and worthy expression of Christianity, as well as defend the principles proclaimed by the Reformers, beginning with Martin Luther, as the fundamental principles of Christianity.

Yahwism: a great reformation in the ancient world

How do we define a Protestant? Simply put, a Protestant is a Christian who places the divine authority of Scripture above the human authority of Tradition and the Church. They are the Christians who believe that salvation is the gift of God’s grace, not the reward of human merit or the fruit of indulgence. These are the Christians who reject the vain and pagan worship of living or dead mediators, who are not credited by God.

If this is what the Protestant spirit looks like, then the historical Christ wouldn’t have been the first reformer. The Jewish prophets who preceded Him must also have had Protestant religious reflexes, as their writings attest. Here is how Isaiah faithfully renders the typical mentality of those who believe that the Holy Scriptures are only meant for scholars and saints—possibly for the priest’s litany, but not for the dirty hands of the peasant:

“For you this whole vision is nothing but words sealed in a scroll. And if you give the scroll to someone who can read, and say, ‘Read this, please,’ they will answer, ‘I can’t; it is sealed.’ Or if you give the scroll to someone who cannot read, and say, ‘Read this, please,’ they will answer, ‘I don’t know how to read.’ ‘These people come near to me with their mouth and honour me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me. Their worship of me is based on merely human rules they have been taught’ (Isaiah 29:11-13).[2]

Biblical Protestantism could be defined by starting from the Ten Commandments and the entire Law of Moses, which essentially places morality above liturgy, and spirituality above religion. The typical temple ritual was important only in a pedagogical sense. It was not effective in itself, but it was a typology of the Gospel. Only specific human mistakes could be forgiven through sacrifices, while capital sins (murder, adultery, perversion, idolatry, blasphemy, violation of the Sabbath, desecration, etc.) could only be forgiven by God, and usually without relieving the culprit of the capital punishment.[3]

The Mosaic Law went beyond the needs of a theocratic legislation specific to the state of Israel, as it educated the individual in the spirit of core motivations: faith and love of God and one’s fellow human beings.[4] And these principles were not only recommended or imposed, but God Himself offered the faithful the superhuman capacity to fulfil them.[5] This emphasis on spirituality and a direct relationship with God, rather than on outward conformity to a law or religious tradition, is of the same spirit as that of the Reformation.

The spirituality in which Jesus was educated was already deeply “Protestant”. No compromise with mystical materialism, disguised polytheism, or magic was acceptable. Orthodox Yahwism was iconoclastic even. Moses’ bronze serpent, raised on a pole like a flag, a prototype of the Cross, was shattered by the faithful Hezekiah, the ancestor of Jesus, as the people began to worship it.[6]

There was no cult of holy prophets or heroes. Moses, the greatest prophet, received no veneration: God had hidden his grave[7] and resurrected his body[8]. There was also no cult of Father Abraham. Isaiah knew that Abraham, like the other patriarchs, was dead and no longer knew anything.[9] Enoch and Elijah, who had been swept up to heaven without seeing death, were not revered as saints[10]. Moses and Elijah were so great before God that they were sent[11] to encourage Jesus Himself, but it did not occur to anyone to worship them or the holy places they had walked on.

This was the simple environment of faith in which Jesus lived. For a Jew, the bones of the dead, whether holy or sinful, were something horrific.[12] Jesus called them, without distinction, “bones of the dead and everything unclean”.[13] He showed no veneration for bodily remains and mocked the Pharisees who cared for dead saints while they were plotting the death of living ones.[14]

The prophet Elisha—a true foreshadowing of Jesus, as Elijah had been a foreshadowing of John the Baptist[15]—performed many miracles. He even raised a dead man.[16] But he worked the greatest miracle after his death: a dead man was resurrected by touching Elisha’s bones.[17] This could have given rise to a cult of relics—a source of material for the clergy or other spiritual entrepreneurs. But such a cult did not emerge. No other dead men were raised by touching Elisha’s bones. Elisha’s bones, if they had the source of life within them, would have prevented the prophet from dying.[18]

If, to these pages of history and law, we add the well-known divine prohibition on the worship of sacred faces, stars, and idols,[19] and if we mention the Gospel, which the prophet Isaiah describes in advance as the climax of this holy law,[20] then biblical Judaism, absorbed by Jesus together with His mother’s milk, was pure Protestantism.

When he declared, “The just shall live by faith” Luther merely repeated a verse which Paul frequently quoted from the poetic oracles of the “Old” Testament.[21]

The need for reform in Jesus’ generation

In Jesus’ generation there was no church yet, much less a pope. Still, Judaism, in its degeneration during Roman times, had reached, in this respect, low points in its development that are comparable to those of later Christianity. Any religious society is in danger of slipping into totalitarianism, legalism, persecution, mysticism, ritualism, and dogged traditionalism. A hierarchy can naturally become oppressive, a dogma or a church commandment can gain greater authority than God’s commandments, and it can threaten the authority of Scripture.

In fact, Judaism in Jesus’ time already had some specific features of medieval Christianity. Consider that the New Testament talks about the synagogue, the Israelite community, ekklesia (assembly, “the church”[22]), and that the Vulgate (the classical Latin Bible) calls the Jewish high priest pontifex,[23] or summus pontifex.[24] But these similarities are merely decorative, and non-essential. However, if we consider the dominant theology of Judaism at that time (Pharisaism), we find the true key to the similarity.

Like later historical Christianity, Pharisaic Judaism had many positive aspects. Education was in the hands of the Pharisees, and their textbook was Scripture. Unfortunately, however, the fundamental doctrines of Pharisaism were often in conflict with the Scriptures. We will only mention three main points, which have remained to this day in traditional Judaism.

First, the Pharisees believed that Scripture and oral tradition (transmitted through rabbis) had the same origin, from God through Moses, and the same authority, which they called the Torah (Law)—written law and oral law. The oral law is now recorded in the Talmud, but is normative for the interpretation of the written law.

Second, the Pharisees upheld the doctrine of salvation by human merit—that is, by meritorious deeds. These meritorious deeds were called the “deeds of the law”, that is, the virtues of conforming to the requirements of the Jewish religion. They taught that man can be righteous (justified) before God by two kinds of merit: the merits of their ancestors (of the patriarchs, for instance) and personal merits.

And third, the Pharisees taught that there is a life outside the body after death: that sinners go into the unquenchable fire of Gehenna, and the righteous go into the bosom of Abraham.

The Pharisees were often lenient about the use of the death penalty under the Law of Moses. That is why they were incomparably more popular than their opponents, the Sadducees. Clemency, manifested in one way or another (the administration of forgiving grace), has always been an attraction of the clerical economy. That is why the pedagogy of many religions consists of emphasizing, on the one hand, the horror of the death penalty and, on the other hand, emphasizing the clerical power to forgive or diminish guilt. The Pharisees, however, had not yet come to invent purgatory, nor the sale of indulgences.

The protest of the Galilean

In such a majoritarian religious setting, the appearance of Jesus Christ, the incarnated God[25], could not help but give rise to a conflict with the Jewish establishment. The real protest is not a biographical or historical accident, but a different philosophy and way of life. Jesus opposed Pharisaism from His childhood. It was a well-known fact that, at a time when primary public education was compulsory for Jews, since the time of Simeon ben Shetach (120-40 BC),[26] Jesus had refused schooling.[27][28]

However, from an early age, he had amazed scholars with His investigative questions and edifying answers.[29] This proved that He was home-schooled (this is where Mary’s “magisterial” grace was manifested!). To this, self-taught study, based on the Holy Scriptures, and manual labour were added.

When we speak of the primacy of Scripture over traditions and of the dignity of work being superior to monastic meditation, we are touching upon two principles specific to Protestant ethics. Rabbis were aware of the educational value of work, and, usually, each of them had a trade, a profession. When it came to religious education, however, mastering rabbinic commandments and traditions was fundamental. This was the only way to be a true believer. Otherwise, one would be at least suspect, if not downright dangerous.

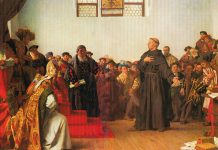

The gestures by which Jesus inaugurated His meeting with the temple authorities—snapping the whip made from cords in the courtyards that had been invaded by the not-so-holy black market, overturning the usurious counters and pigeon cages[30]—are in many ways similar to Luther’s 1517 outburst against the extravagant show of selling indulgences. Jesus’ indignation was similar, but much amplified. The institution that Jesus called “My Father’s House” and which had been designed for missionary purposes,[31] had become “a den of robbers”,[32] a space of dishonest trade.

Three years later, when, coming to the temple, Jesus saw the courtyard flooded by the same usury, He turned for a moment into a defender of the divine order. This time, however, without a whip, using only Scripture verses.[33]

Kăthīv: “It is written”

Although He did not convey the Latin formulas of the Reformation program (Sola Scriptura, Prima Scriptura, Tota Scriptura), Jesus expressed equivalents of these principles in His own language.

First and foremost, it is good to understand that Jesus did not have any kind of psychosis or fixation regarding the manifestations of popular or rabbinic traditions. It was not tradition as such that bothered Him, nor was He set on destroying habits as long as they were innocent, and not imposed on people. At the wedding in Cana, for example, He used the water destined for the rabbinic ritual of the washing of the hands as raw material for His first miracle.[34]

When talking to the Samaritan woman, Jesus could have protested against the claim of the Samaritan tradition that the well had been dug by the great patriarch Jacob himself almost two millennia ago.[35] He asked to drink from the water of that well of the lost[36] because water is God’s gift, regardless of the identity of the owners or who dug the well. At the Bath of Bethesda, Jesus has another meeting with water, in the form of the legend of the source of healing.[37] This time, too, He does not explicitly wage war with tradition, but freely proclaims that salvation comes only from faith in God’s Word.

However, when faced with the accusation of neglecting tradition, Jesus responded by exposing the hypocrisy of all religious people who break divine commandments in order to maintain sacred traditions:

“Then some Pharisees and teachers of the law came to Jesus from Jerusalem and asked, ‘Why do your disciples break the tradition of the elders? They don’t wash their hands before they eat!’ Jesus replied, ‘And why do you break the command of God for the sake of your tradition? […] Thus you nullify the word of God for the sake of your tradition. You hypocrites! Isaiah was right when he prophesied about you: ‘These people honour me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me. They worship me in vain; their teachings are merely human rules’.'” (Matthew 15:1-9; see also Mark 7:5-13).

While placing religious hopes or fears related to traditions under the generic description “in vain” Jesus quotes Holy Scripture as the supreme authority. Jesus’ usual line and reply, both when talking to the people and in His confrontation with theologians or the devil himself, was the Judeo-Aramaic word kăthīv (“it is written”, see Matthew 4:4, 7, 10; 21:13; 26:13).

By confronting the temptations of the devil, religious traditions, or human propositions, Jesus could have brought forth His own authority. Wasn’t He God? Wasn’t He the Christ? Wasn’t the power of the Holy Spirit always at His disposal? Hadn’t He already done so many miracles? But He never explicitly asserted His authority as God.

It is equally astonishing that Jesus commanded both His disciples and the demons not to go around telling people the fact that He was the Messiah, the Christ.[38] People needed to understand the message of His teaching and deeds, and, above all, the Scriptures.

After the resurrection, when He could have used this mountain of His miracles as a sufficient argument for His authority, Jesus instead preferred to emphasize the authority of Scripture. He took the time to remind them of the whole series of messianic prophecies throughout the Hebrew Scriptures,[39] to imprint on their minds that one must keep in mind all that the Scriptures teach.[40]

The authority that Jesus left behind is the living Spirit and the Word—no bones of the dead, no holy wood or rags, no magical deeds, no human intercessors, no religion of the dead or vain hopes. The only power left to the apostles was the Holy Spirit, the power of the resurrection, and Scripture—the only religious standard for continuous reform.

Finally

If Jesus’ Christianity does not resemble our Christianity, a new protest and a new reforming is needed. One of the characteristics of a truly Reformed church is semper reformanda (a church that is always reforming). Traditionalist churches do not seem to have learned much from the Reformation five centuries ago, and Protestant churches themselves need a return to the principles of the Reformation: the authority of the Bible over synodal authority, over theological currents, and over any human or supernatural authority. Reform does not mean change for the sake of change or according to principles other than biblical ones.

The salvation of Christianity will not come through solutions that are fatally pleasing to the majority, such as returning to the “Holy Tradition” or experiencing the supernatural. The only salvation is: “It is written!” Beyond this lies an empire “in vain”, the religion of futility and human vanity. However, the reform of the church as an institution is unlikely. Not because the church is damned, but because the spiritual alteration has penetrated too deeply. Those who want to follow Jesus are often forced to abandon the religious community that is based on other values.

Christianity has never experienced more dangerous times. If, when it comes to human aspects related to culture, administration, and formalities, we must go forward, when it comes to the principles of faith and religious practice we must always go back to the origins. We are not called to return to the traditions of the year 313 or the traditions of the years 160 or 30, but we are called back to the Word of God.

The church is not a simple historical institution, inextricably linked to ecumenical councils or apostles. It is a living institution, led by the Holy Spirit, through the supreme authority of Scripture. Only this phrase, “It is written!”, as a confession of faith, can defeat the devil. Any alternative is “in vain!”